Retiring Judge Gary Andrews Breaks His Silence

The Court of Appeals revealed a portrait Thursday of its quietest judge—who after 28 years had a lot to say.

August 09, 2018 at 07:16 PM

6 minute read

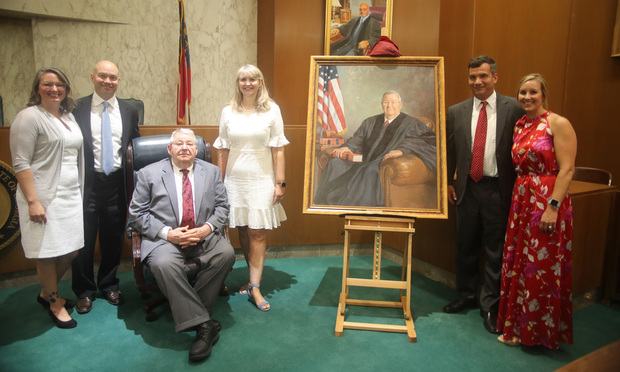

Tiffany Painter (from left), Blake Andrews, Chief Judge Gary Andrews, Paige Andrews, Blane Andrews and Heather Andrews with the judge's portrait.

Tiffany Painter (from left), Blake Andrews, Chief Judge Gary Andrews, Paige Andrews, Blane Andrews and Heather Andrews with the judge's portrait.

Recently retired former Chief Judge Gary Andrews of the Georgia Court of Appeals did something unusual from the bench Thursday. He talked.

In his 28 years on that bench, Andrews was known for silence, rarely uttering a word, let alone a question. When asked recently in a panel discussion at a State Bar of Georgia event if judges ever show off for the cameras, now that oral arguments are shown live on the internet, Chief Judge Stephen Dillard got a big laugh when he answered: “Gary Andrews is notorious.”

But it was Andrews getting the laughs Thursday in a portrait unveiling ceremony—which, like the court's oral arguments, was livestreamed on its website. He entertained a courtroom packed with colleagues, friends and family gathered in the courtroom, telling stories about his 47-year legal career, including 28 years on the Court of Appeals, which wrapped up last week.

First of all, unlike many of his contemporaries, he was not inspired to become a lawyer by “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

“I wanted to be Mickey Mantle,” Andrews said. “I did not want to be … what's his name?”

“Atticus Finch,” his colleagues replied, helping him out.

Right. He didn't want to be Atticus Finch.

Andrews said his “epiphany” for becoming a lawyer came in Athens a few years later, in 1965, thanks to his performance in a University of Georgia chemistry lab. After he decided on law school, he majored in accounting as a backup. After law school, he planned to become a tax lawyer because his best offer was from an accounting firm. This might not surprise those who have noticed his pro-business tendencies as a judge on the intermediate appellate court.

But at the last minute, he got a call from Georgia Attorney General Arthur Bolton's office, saying the boss was concerned that he'd been hiring too many Emory law grads. He was offered a job and took it in 1971.

Bolton was a great mentor and a respected and feared boss, Andrews said. He recalled being new on the job and seeing a memo from “Mr. Bolton” saying that one of his assistant attorneys general had let a case go into default. “If that happens again, please use the attached form,” it said. The attached form read, “I hereby resign.”

It was hard to leave, Andrews said. But, by 1977, he longed to hang out his own shingle back in his hometown of Chickamauga, population 2000, in the far corner of northwest Georgia.

“I wanted to raise my family in Mayberry,” he said, referencing the fictional home of “The Andy Griffith Show.”

His old boss made that happen, too, he said, sending him cases to handle as a special assistant AG involving the Department of Transportation, workers' compensation, even transactional work for Cloudland Canyon State Park.

Then, when a seat came open on the Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit Superior Court, he ran for it and narrowly won.

He also served on the Georgia Public Service Commission before running for the Court of Appeals. Andrews, 71, was first elected to the Court of Appeals in November 1990 and took office in January 1991. He was re-elected to office four times, with his current term set to end in December 2020. He served as the Court of Appeals' chief judge from 1997 to 1998, and his tenure on the court is the third longest in its history.

If there was a theme to the talk, it was change. Andrews said the court has transformed in his time from nine members to 15 and become more diverse in age, gender and geography. “It used to be extremely stable. People didn't leave,” Andrews said. “Now they're coming and going.”

Gov. Nathan Deal has appointed seven new judges out of the 15 in just over two years.

Three of those came at the start of 2016 when Deal expanded the court from 12 to 15 members—and gave it additional responsibilities to relieve the burden on the Georgia Supreme Court. Then, a year after that, Deal moved one of those three—Nels Peterson—up to fill an opening on the high court. (The other two are still there: Amanda Mercier and Brian Rickman.) That gave Deal another appointment to replace Peterson, Charlie Bethel. Plus, Deal appointed Clyde Reese when Herbert Phipps retired.

This year, Deal has appointed two judges—Trent Brown and Elizabeth Gobeil—as replacements for two who scored lifetime federal appointments by President Donald Trump—Tripp Self and Elizabeth Branch. Plus, Deal appointed Stephen Goss to succeed Andrews. One more appointment is likely to come soon, as Billy Ray awaits confirmation to another Trump appointment to federal court.

Andrews might have liked one benefit his colleagues moving on to federal court will have—not having to run for election. He made several jokes about his “50.1 percent mandate.” And he didn't skip over his highly contentious 1996 election, when he was targeted by plaintiffs' lawyers who thought he was too favorable to the defense in civil cases. But he won with another “50.1 percent runaway,” as he put it.

“I could be a politician for three or four months, but I couldn't do it year-round,” he said. He added he wouldn't even want to have to walk into the diner in Chickamauga and have to speak to everyone there. “That's not me,” he added.

Friend and colleague John Ellington joked, “There are people there.”

“Yes,” Andrews said. “I don't like that.”

But then, the portrait was unveiled and Andrews was surrounded by people, wishing him well and celebrating his 47-years-long legal career—which he said was better than “hauling hay.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

12-Partner Team 'Surprises' Atlanta Firm’s Leaders With Exit to Launch New Reed Smith Office

4 minute read

After Breakaway From FisherBroyles, Pierson Ferdinand Bills $75M in First Year

5 minute read

On the Move: Freeman Mathis & Gary Adds Florida Partners, Employment Pro Joins Jackson Lewis

6 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250