'Incomprehensible,' 'Scary,' 'Frivolous': Justices Blast Fulton's 'Miranda' Argument

A Fulton prosecutor tried to defend a judge's refusal to suppress statements from a murder defendant who said he didn't want to talk to police multiple times.

August 22, 2018 at 07:06 PM

8 minute read

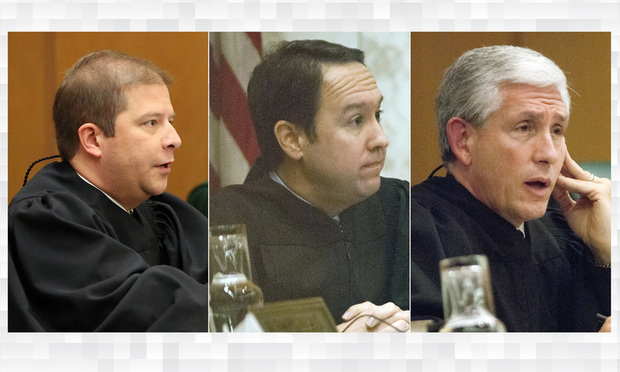

Justices Nels Peterson (from left), Keith Blackwell and David Nahmias, Supreme Court of Georgia.

Justices Nels Peterson (from left), Keith Blackwell and David Nahmias, Supreme Court of Georgia.

A murder suspect kept telling police officers he wished to remain silent, but when his case came before the state Supreme Court, three justices had plenty to say.

“Counsel, it is incomprehensible to me that the state of Georgia is standing here making this argument,” Justice Nels Peterson told Fulton County prosecutor Stephany Luttrell. She'd just argued that officers were not required to assume a suspect who said he didn't want to talk understood his right to remain silent under the landmark Miranda v. Arizona decision from the U.S. Supreme Court.

Justice David Nahmias chimed in that it was “scary that the largest county in Georgia has counsel and police officers that apparently believe what you are saying.”

A few minutes later, Justice Keith Blackwell urged Luttrell to shift to the state's claim that the defendant's incriminating statements were admissible because they came after he agreed to speak with one officer only if his partner wasn't in the room.

“I don't know that that one's a winner,” Blackwell mused, “but it does have the virtue of not being completely frivolous.”

Luttrell pleaded, “If I could, Justice Blackwell, just one more thing,” before Peterson interrupted with, “That's a very bad idea.”

Nahmias, Peterson and Blackwell were the only justices of the eight who heard the case on Aug. 6 to speak. Justice Britt Grant had just been confirmed to a federal appeals post, and Gov. Nathan Deal just appointed Sarah Warren from the Attorney General's office as her replacement. A court spokeswoman said Grant's replacement and any other new justice—Chief Justice Harris Hines is set to retire on Aug. 31—would be able to participate in the decision by reading the briefs and watching video of the argument.

'All I know is I didn't do nothing'

At issue was an appeal by Michael Grant, who was sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of felony murder of Christopher Walker. Grant was accused of driving the getaway car for an acquaintance who in 2013 fatally shot Walker during an attempt to steal Walker's gold neck chain.

After Grant was arrested two weeks after the incident, he sat with his hands cuffed in front of him in an interview room in Roswell with two officers from the Milton Police Department identified as Detective Barry and Sgt. J. Griffin. The interview was video-recorded, and there appears to be no dispute about what occurred.

According to a transcript, Barry asked Grant a few biographical questions and then asked, “Do you want to waive your Miranda rights and let us tell you what this is about?”

Grant, then 23, responded: “Do I want to waive my rights? No.”

He went on to say three more times he didn't want to waive his rights, one time uttering, “I don't got nothing to say.”

The officers told Grant he was under arrest for murder and other charges, then left the room, with Barry saying, “Why don't you think about it?”

When they returned 10 minutes later, Barry read Grant his Miranda rights, saying he had a right to remain silent, to have an attorney and to stop talking at any point. Grant said he understood, then said, “All I know is I didn't do nothing.”

Asked to sign a waiver of his Miranda rights—”just a procedural thing,” said Barry—Grant then said, “If I'm already under arrest, then I don't got nothing to say about nothing.”

Asked again to sign, Grant did so. The ensuing conversation meandered, with the officers asking about the killing, Grant saying his cousin Matthew Goins—who was also in the car that night—did nothing wrong, and Grant saying he again had nothing to say.

Grant asked to call his mother, promising to speak with the officers after the call. The officers refused, saying since he was the first of three suspects arrested, word could get out to the other two suspects. A moment later, Griffin and Grant briefly argued, and it appeared Grant was ready to be transported to the jail when he said to Barry, “If it wasn't for him [Griffin], I probably would have said something to you.”

Barry asked if Grant would talk to him, and Grant did. The key parts of what Grant said came up at his trial. Prosecutors told jurors that Grant admitted to being at the scene of the killing and that he drove Richard Davidson, who would be convicted of firing the gun that killed Walker, away from the scene.

Before trial, Grant's lawyer Joshua Geller asked Judge Kimberly Esmond Adams of Fulton County Superior Court to suppress the statements Grant made to the police, arguing that Grant clearly had invoked his Miranda rights to remain silent and that his subsequent waiver wasn't freely or voluntarily made.

Adams rejected the motion, noting that Grant's refusal to speak to the officers came before they formally read him his Miranda rights. “In order to have an unequivocal response, there first must be an actual advisement of the rights one is either invoking or waiving,” Adams concluded.

Grant and Goins were tried together, with Grant being convicted of felony murder and other charges leading to a life prison sentence plus another five years. Goins was acquitted.

A Tough Assignment

At the state Supreme Court, Grant was represented by Mableton lawyer Ben Goldberg, who spoke mostly without interruption by the justices. “Law enforcement failed to scrupulously honor” Grant's clear invocation of his Miranda rights, Goldberg said, arguing that Adams' decision was wrong.

Attorney General Chris Carr and Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, with their staffs, submitted separate briefs defending Adams' decision. But it fell to Luttrell—who was not one of the three prosecutors listed on Fulton County's brief—to explain the state's position before the Supreme Court.

She said the trial court correctly denied Grant's motion to suppress statements he gave to police “on the ground that Mr. Grant did not unambiguously and unequivocally invoke his Miranda rights before officers left the room.”

“That is a very hard thing to credibly stand up here and say,” Nahmias responded. He and other justices ticked off statements by Grant such as, ”Do I want to waive my rights? No”; “I'm not waiving anything'”; “un-unh” to a question about whether he wanted to talk; and “I don't got nothing to say.'”

“That is an unequivocal invocation of the right to silence, right?” asked Nahmias, looking incredulous.

Unbowed, Luttrell started to respond when Peterson interrupted: “Can you cite a single case that supports the idea that when a defendant has said this many times that he hasn't invoked his Miranda rights?”

After accidentally calling Peterson “Justice Blackwell,” Luttrell apologized and then said, “There aren't cases on either side.”

“Yes there are,” Nahmias interjected. “You don't think we have cases?”

Luttrell responded that in other cases on this issue, the defendant had already been advised of his rights, but in Grant's case, he hadn't been read his Miranda rights.

“Do you have to be told by the state that you have a right to counsel before you are allowed to exercise your right to counsel or your right to remain silent?” Nahmias asked.

Luttrell later argued that Grant's refusals to talk were equivocal, requiring clarification by the officers. She noted that, just after agreeing to waive his rights, he said, ”All I know is I didn't do nothing.”

“He evinced an intent not to want to remain silent,” she insisted.

“You don't get to clarify unequivocal statements,” Nahmias said. “The Supreme Court and our court have said when it's unequivocal, you got to stop.”

Adopting a humorous tone, Nahmias imagined an interrogation where officers questioned unequivocal statements: “You said, 'I got nothing to say.' Did you mean I got nothing to say? Let's talk some more about that.”

Peterson asked whether refusing to suppress Grant's statements could be considered a harmless error that ultimately did not affect the outcome of the trial, which would leave Grant's conviction intact.

Luttrell responded that there was circumstantial evidence that Grant was involved in the crime, but Nahmias was skeptical. He suggested that other than Grant's statements to the police, the evidence against Grant was nearly identical to that of his cousin, Goins, who was acquitted.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

A Plan Is Brewing to Limit Big-Dollar Suits in Georgia—and Lawyers Have Mixed Feelings

10 minute read

On The Move: Kilpatrick Adds West Coast IP Pro, Partners In Six Cities Join Nelson Mullins, Freeman Mathis

6 minute read

Did Ahmaud Arbery's Killers Get Help From Glynn County DA? Jury Hears Clashing Accounts

Trending Stories

- 1Don’t Blow It: 10 Lessons From 10 Years of Nonprofit Whistleblower Policies

- 2AIAs: A Look At the Future of AI-Related Contracts

- 3Litigators of the Week: A $630M Antitrust Settlement for Automotive Software Vendors—$140M More Than Alleged Overcharges

- 4Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 5Linklaters Hires Four Partners From Patterson Belknap

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250