Yates Says Broad Coalition Aims to Break 'Over-Incarceration' Cycle Despite Trump Shifts

The former deputy attorney general said the Trump administration has largely abandoned reforms, such as literacy classes, that she made to the federal prison system, but reformers "across the ideological spectrum" are at work in the states.

August 23, 2018 at 04:20 PM

5 minute read

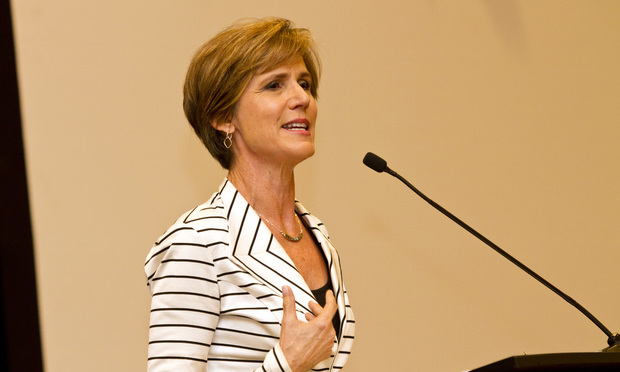

Sally Yates, former U.S. deputy attorney general, was the keynote speaker Thursday at NACDL's annual State Criminal Justice Network Conference in Atlanta. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Sally Yates, former U.S. deputy attorney general, was the keynote speaker Thursday at NACDL's annual State Criminal Justice Network Conference in Atlanta. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Former federal prosecutor Sally Yates received a standing ovation from a roomful of criminal defense lawyers at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers' annual conference on Thursday.

The group honored Yates with its Champion of Justice Restoration of Rights Award for her work to advance education in prison and promote successful re-entry into society when she was deputy attorney general in the Obama administration after serving as U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Georgia. She is now a partner in the special matters and government investigations practice at King & Spalding.

NACDL's conference focus this year is “shattering the shackles of collateral consequences” for people who've served their sentences and returned to society.

Yates said in her keynote speech that she saw firsthand the problems that people returning from prison face through a re-entry program that she started as U.S. attorney in Atlanta.

Her office partnered with local service providers to connect recent re-entrants with assistance through an event at Lindsay Street Baptist Church in Atlanta's English Avenue neighborhood, a notoriously blighted area at the time.

“We were confronted with stark realities,” Yates said. First of all, the turnout was three times what they'd expected. In addition to the formerly incarcerated who'd signed up, there were plenty of other people in the community needing the same education, employment and substance abuse services—and still others who couldn't believe prosecutors were doing a program to help people coming out of prison.

“This did not make any sense to them,” Yates explained.

The organizers asked the re-entrants to fill out a form indicating what kind of assistance they needed but, oddly, a lot of people didn't. When Yates asked one man why he hadn't returned his form, she said, he told her he couldn't read.

That's what drove it home for her, Yates said, that those basic needs for education, job skills, mental health and addiction treatment had to be addressed in prison so people “have a fair shot at being successful when released.”

“It's too late if you start to talk about the things folks need when they walk out the door,” Yates added, prompting a round of applause from the roomful of criminal defenders.

When Yates went to Washington, she quickly started working with the Bureau of Prisons to improve its rehabilitation programs. “It's the right thing to do—and it's the smart thing to do from a public safety and fiscal perspective,” she said.

She found out from the bureau that they offered English language classes but no classes on how to read. The GED preparation program had more than 10,000 people on the waiting list, Yates said, and those in the program received only an hour a day of classroom instruction.

During Yates' two-year tenure, the BOP created a semi-autonomous school district to coordinate its educational programming. Under the new system, each inmate received an individualized education plan on entering prison, which went with them from facility to facility. The agency started literacy classes and shifted the focus from GED preparation to earning a high school diploma, Yates said, because the latter is more valuable for landing a job.

The BOP's jobs program was about to go out of business when Yates became deputy attorney general, but she said her office found a retired Fortune 100 executive who turned it around so federal prisons can train inmates for the jobs of the future.

In a key policy decision, the DOJ stopped using private prisons, which Yates said “do not provide the same kind of safety or services that federal prisons do,” and stepped up its review of halfway houses, which she called “spotty at best in providing services.”

One simple but important change at the BOP during Yates' tenure was to start providing each inmate with a birth certificate, certified state identification card and Social Security card upon release—key documents for people to procure housing and jobs. It also gave them a handbook that listed resources and opened a re-entry hotline staffed by prisoners for the newly released people to call with questions.

“Sadly and inexplicably, the new administration discontinued almost all the programs I've outlined,” Yates said—the education programs in particular.

The private prisons are back in business, she added, and now the emphasis is on harsher punishment and longer sentences, which perpetuates the “cycle of poverty and recidivism.”

Instead, it is the states that are taking on the country's “over-incarceration problem,” Yates said.

“At the risk of stating the obvious, there is a whole lot of division in this country right now,” she said. “But criminal justice reform is one of the few issues where there is a consensus across the ideological spectrum.”

“People coming out of prison are trying like crazy to get a job—and [can't] even get in the door,” she added. “We're not just talking about policies, we're talking about people—with children, families, hopes and dreams, and tragedies in their lives.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

40% Contingency: A New Ruling Just Cost This Plaintiff Team $827K in Legal Fees

6 minute read

'David and Goliath' Dispute Between Software Developers Ends in $24M Settlement

Trending Stories

- 1SDNY US Attorney Damian Williams Lands at Paul Weiss

- 2Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Norton Rose Sues South Africa Government Over Ethnicity Score System

- 5KMPG Wants to Provide Legal Services in the US. Now All Eyes Are on Their Big Four Peers

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250