Equifax headquarters, Atlanta (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Equifax headquarters, Atlanta (Photo: John Disney/ALM)Consumer Lawyers Take Aim at Equifax Motion to Dismiss Data Breach Cases

Attorneys representing hundreds of consumer plaintiffs whose financial and personal information was exposed in a massive data breach at Equifax last year challenged arguments by the credit bureau's lawyers that no one suffered harm, and if they did, Equifax is not at fault.

September 05, 2018 at 02:55 PM

4 minute read

Lawyers suing Atlanta-based credit bureau Equifax over a massive data breach have branded company efforts to dismiss the litigation a “perverse argument … akin to the 'too big to fail' rationale that lead to the Great Recession.”

Responding to the company's motion to dismiss hundreds of complaints against Equifax, counsel for consumers whose financial and personal data was exposed scoffed at Equifax lawyers' claims that no one was actually harmed and that it had no legal duty to safeguard the personal and financial data it routinely collects and monetizes.

“In fact, the need for a duty in such circumstances is even more critical to ensure that companies have an incentive to spend the money needed to prevent the harm in the first place, rather than allowing them to shift the expense of failing to do so to innocent third-parties,” consumer lawyers contended in their Aug. 13 response.

Ken Canfield of Atlanta's Doffermyre Shields Canfield & Knowles, Amy Keller of DiCello Levitt & Casey in Chicago and Norman Siegel of Stueve Siegel Hanson in Kansas City are co-lead counsel for hundreds of consumers who have filed lawsuits stemming from the exposure of their personal and financial data. Equifax has acknowledged that the personal and financial data of about 143 million consumers may have been exposed or stolen by hackers.

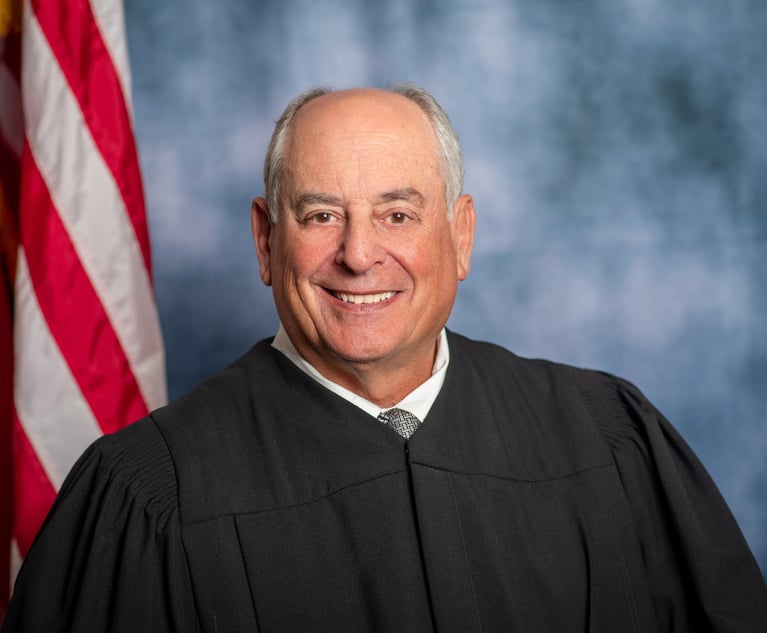

The cases have been consolidated in multidistrict litigation in federal district court in Atlanta. Chief Judge Thomas Thrash Jr., who has presided over multidistrict litigation over a data hack at Atlanta-based home supply chain The Home Depot, is presiding in the Equifax cases.

A team of King & Spalding lawyers led by partners David Balser and Phyllis Sumner, represents Equifax. In a July 16 motion, Balser argued that claims brought by consumers, credit unions, banks and associations for financial institutions were based on an “attenuated theory of liability” that is unprecedented and “far-fetched.” And, in a June 27 motion, Equifax argued that a 566-page consolidated complaint on behalf of consumers was “long on words” but “short on operative facts.”

In both motions, Equifax argued a common defense in data breach cases: The vast majority of plaintiffs lacked standing to sue in federal court because they had no injuries from the breach—just speculation about the increased risks of identity theft.

In response, consumer lawyers contended that everyone whose confidential data was exposed was harmed in multiple ways that other judges, including Thrash, have determined were valid.

Those alleged injuries include:

- Spending time and incurring out-of-pocket loss addressing issues relating to identity theft and fraud;

- Purchasing credit monitoring and credit freezes to mitigate possible harm;

- Monitoring financial accounts;

- Experiencing a decline in credit scores, which jeopardizes their borrowing ability and causes other problems;

- Lost opportunity costs, unauthorized withdrawals from their accounts and the loss of value of personal information; and

- Imminent risk of future harm.

“To the extent Equifax questions whether [the plaintiff consumers'] mitigation expenses were necessary or recoverable, those are jury issues,” consumer lawyers contended.

“The cost to Equifax of having adequate data security is a small fraction of the damage it has imposed on plaintiffs and the consumer credit system,” they said.

Consumer lawyers also took aim at Equifax arguments that consumers whose data was stockpiled could not claim they had been duped by alleged company misrepresentations about data security because the credit bureau does not generally obtain information directly from consumers, but, instead, collects the bulk of its data from third parties.

That argument ignores the “special role in the consumer economy in which [credit reporting agencies] are authorized to gather [consumers'] confidential information and, in highly regulated circumstances, disseminate that information,” consumer lawyers said.

“The reality is that all of the actors in the consumer economy―including [the plaintiff consumers], data furnishers, and regulators―relied to their detriment on Equifax's actions,” they contended. “By misrepresenting the truth regarding its commitment to data security and failing to disclose that its existing security measures were virtually non-existent, Equifax deprived the marketplace, including [the consumer] plaintiffs, of critical information needed to make informed decisions. Had the truth been known, [consumers] and the other actors could have taken protective action, such as refusing to do business with Equifax and those who furnished data to Equifax, or otherwise adjusting their behavior.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

North Carolina Courts Switch to Digital, Face Extreme Weather in 2024

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250