Judge Facing Ethics Charges Calls Judicial Watchdog Agency Unconstitutional

Pike County Superior Court Judge Mack Crawford is fighting back against charges accusing him of impermissibly laying claim to more than $15,000 that had been in the clerk registry for 16 years.

September 20, 2018 at 01:03 PM

5 minute read

Judge Mack Crawford, Griffin Judicial Circuit (Courtesy photo)

Judge Mack Crawford, Griffin Judicial Circuit (Courtesy photo)

A Pike County Superior Court judge facing ethics charges that could result in his removal from the bench claims the state judicial watchdog agency that pressed claims against him was illegally constituted two years ago and has no authority to discipline him.

Former Georgia Gov. Roy Barnes, who is defending Judge Robert “Mack” Crawford in the ethics inquiry, also contends that, when the formerly independent state Judicial Qualifications Commission was abolished by constitutional amendment in 2016 and re-established as a creature of the Georgia General Assembly, no provision was included to allow the new JQC to take disciplinary measures against a judge for actions that took place before the amendment passed.

It is not the first time that legislative language that abolished the original independent JQC has been called into question.

Members of the Georgia House of Representatives who led the 2016 push to abolish the JQC as an independent constitutional agency in favor of one over which it had sole oversight and control of, included contradictory language about when a newly configured JQC governed by different procedures would take effect. The glitch resulted in the creation of an interim JQC on Jan. 1, 2017, that was abolished on June 30, 2017, in favor of the current commission.

The Judicial Qualifications Commission filed formal ethics charges in July against Crawford that accused him of “impermissibly” acquiring $15,675.62 from the Pike County Superior Court registry fund. Pike County is part of the Griffin Judicial Circuit, which includes, Fayette, Spalding, Upson and Pike counties.

The charges stem from four separate complaints filed against Crawford with the JQC.

The JQC contended the funds either belonged to Crawford's client or should have been treated as unclaimed property to be turned over to the Georgia Department of Revenue. The agency also said that, even if the funds belonged to Crawford, he was required by law to issue a formal court order to the clerk to disburse the funds rather than a handwritten note he gave to the clerk directing her to write him a check from the court registry.

The formal charges also put Crawford on notice that the JQC could pursue additional ethics charges against him regarding allegations he routinely fails to schedule hearings, issue orders or otherwise resolve pending cases in a timely fashion.

In his formal response, Crawford said he has not been chronically sluggish in performing his judicial duties. He blamed any delays on the circuit's failure to provide him with a legal assistant, courtroom space or a printed calendar. He also blamed illness.

The response also reiterated Barnes' earlier assertions that Crawford was duly owed the money. Crawford said he deposited it into the court registry 16 years ago on behalf of a client—after he filed a complaint for a redemption of a tax deed to forestall foreclosure of the client's home.

Client Dan Mike Clark informed Crawford at the time “his desire was to be able to stay on the property throughout his lifetime and, upon his death, any funds remaining in the registry of the court could be taken as a fee,” the response said. Clark continued to live in the house until he died in April 2004. A judge dismissed the inactive case in 2009.

In his response, Crawford said he “forgot about the money in the registry until 2017” when the court clerk notified him the funds he deposited in 2002 were still there. According to Crawford, the clerk “asked if he would take possession of the funds,” and he “agreed to do so” because he was entitled to them as an unpaid legal fee.

Crawford acknowledged that when the JQC, acting on a complaint, asked him about the money, he returned it to the registry and it was subsequently forwarded to the state Department of Revenue as “abandoned funds.” The JQC said he did so only after he learned of the ethics investigation and a parallel, ongoing law enforcement probe by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Crawford said he still has a right to the money and has filed a petition in Pike County Probate Court to “manage the affairs” of his late client so that he can make a formal claim against the estate for unpaid fees.

But Barnes argued in Crawford's response that the current JQC is unconstitutional, because the legislation that gave the Georgia General Assembly sole authority to recreate it violates the state Constitution's separation of powers clause by allowing legislative and executive appointments. The JQC operates under the auspices of the state judicial branch.

While the constitutional amendment passed Nov. 8, 2016, allows the General Assembly to create the JQC, “unlike its predecessor it does not allow a violation of the Separation of Powers clause,” Crawford's response contends. “As such, statutory enactment of the General Assembly creating the JQC … is invalid and unconstitutional.”

In addition, the 2016 constitutional amendment included “no saving provision … allowing any acts prior to the ratification of the amendment to be the basis for discipline,” the response said. Even if such a provision had been included, it would violate the state constitution which prohibits the passage of retroactive laws, the response said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Judge Admits to Judicial Misconduct as Charged, but Denies Willful Misconduct

4 minute read

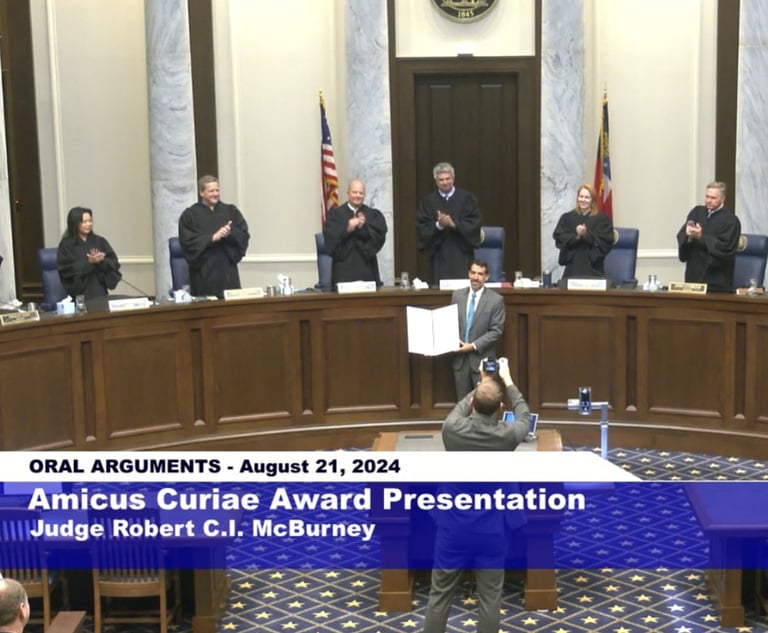

Judge Gets Standing Ovation for Service to State's Judicial Watchdog Commission

6 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'Every MAGA Will Buy It:' Elon Musk Featured in Miami Crypto Lawsuit

- 2Pennsylvania Law Schools Are Seeing Double-Digit Boosts in 2025 Applications

- 3Meta’s New Content Guidelines May Result in Increased Defamation Lawsuits Among Users

- 4State Court Rejects Uber's Attempt to Move IP Suit to Latin America

- 5Florida Supreme Court Disciplined 17 Attorneys

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250