Will Murder Conviction Reversed by Supreme Court Lead to Retrial?

“We will definitely retry this case,” Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard said after the Georgia Supreme Court's unanimous reversal. “It is a murder.”

September 26, 2018 at 05:03 PM

8 minute read

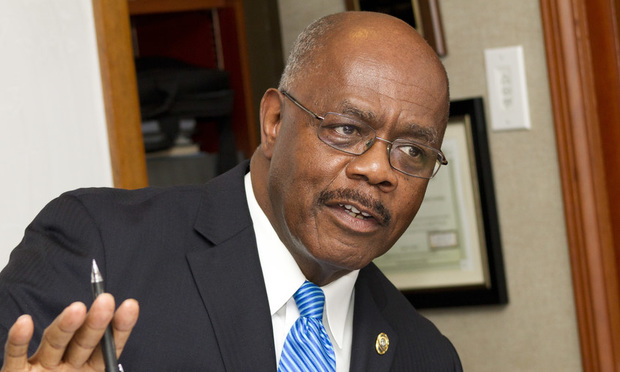

Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Prosecutors say they plan to retry a man whose murder conviction the Georgia Supreme Court reversed Monday based on an interrogation that took place after he invoked his right to remain silent, but the defense says the second trial would include “not much” evidence with the statement tossed.

“We will definitely retry this case,” Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard said by email Monday evening, following the Supreme Court's unanimous decision in State v. Grant. “It is a murder.”

Assistant District Attorney Stephany Luttrell represented Howard's office in the appeal. She said Michael Grant's statement should be admissible, even though it came after police repeatedly pressed him. The justices called that argument “incomprehensible,” “scary” and “frivolous.”

Howard did not address the opinion specifically or address that argument.

“As for as any comments about the court's decision, we can only add our general practice is to follow the facts and to leave the 'criticizing' and 'journalism' to others,” Howard said. “We have represented the State and Fulton County in hundreds of matters before this court, with overwhelming success. In fact, our decisions outnumber other jurisdictions by a wide margin. It is my hope that readers of the opinion will keep these facts in mind when considering what was said in this single case.”

Howard offered no details on what evidence the state would rely on without Grant's statement—in which, according to documents, he acknowledged driving the car when his passenger, Richard Davidson, got out and fatally shot another man, Christopher Walker, while attempting to steal a gold chain. The Supreme Court overturned Grant's felony murder conviction and life sentence and ruled his statement inadmissible because he first told police, “I'm not waiving nothing,” and “I ain't got nothing to say.”

But police wore him down, telling him they wanted to hear his side and explain why he'd been arrested, and eventually he talked, according to the opinion authored by Justice Keith Blackwell. It seemed Grant was trying to help his cousin, Matthew Goins—whom Grant said had nothing to do with the crime and was just trying to get a ride home.

Goins was acquitted of all charges in a joint trial with Grant. Davidson was convicted in a separate trial. The Supreme Court upheld Davidson's murder conviction Monday.

Benjamin Goldberg (Courtesy photo)

Benjamin Goldberg (Courtesy photo)“Without his statement, they really can't necessarily prove he was driving the car,” said Ben Goldberg, who handled Grant's appeal. “Essentially the evidence is about the same as that of the defendant who was acquitted, his cousin.”

According to his defense attorney, Grant thought Davidson was getting out of the car to try to buy marijuana and didn't even know about the gun, let alone plans of robbery or murder.

The facts presented in the opinion reflected that Davidson asked for the gold chain after being turned down for a drug buy, then pulled out the gun after being refused the chain. Then he got back in the car and told Grant he had shot someone and to drive away, the court said.

Police were able to implicate Grant with one word he used in the statement he eventually gave: In trying to exonerate his cousin, Grant said, “He didn't know we planned on doing nothing; he was just trying to get home.”

Grant's use of the word “we” did not mean he knew what Davidson was going to do, but police used it to suggest Grant did know what was going to happen, according to Goldberg.

Goldberg called the parsing of the statement an example of “the reason you don't want the cops badgering people” to talk.

“When somebody's right to remain silent is not scrupulously honored, which is what the law requires, the result is, statements are made which are not reliable and can be twisted multiple ways,” Goldberg said.

Christopher Walker died on March 12, 2013. According to Blackwell's opinion, Walker and his friend, Alberto Rodriguez, went out to eat at a Taco Bell in Alpharetta. Rodriguez later testified that, as he and Walker entered the restaurant, they passed three men who were outside talking to one another, later identified as Grant, Davidson and Goins. Rodriguez said he thought he noticed Goins eyeing the gold chain Walker wore around his neck. Later, when he and Walker came out of the restaurant, Rodriguez noticed that Grant's car had moved across the street and was now facing the Taco Bell. Three people were in the car, one of whom Rodriguez recognized as the same man who had been eyeing Walker's chain, but he said he didn't “think too much of it” at the time. He and Walker then proceeded to drive to Walker's home in Milton.

As Walker and Rodriguez were getting out of the car at home, they were approached by someone later identified as Davidson, who asked Walker and Rodriguez if they knew where to get some marijuana, according to the court. When they said no, Davidson at first started to walk away but returned and told Walker he liked his gold chain. Davidson then pulled out a gun and demanded Walker's chain. When Walker refused, Davidson held the gun to Walker's head and, following a brief struggle, shot him, the court said. As Rodriguez ran to call for help, he saw Davidson flee to Grant's car, and Grant then drove Davidson away from the scene “at a high rate of speed.” Walker died later that night.

Grant, Goins and Davidson were later identified by someone who knew them via “Crime Stoppers,” a service used by law enforcement to obtain help from the public.

Grant was brought to the Roswell Police Department, where he was interrogated by Milton police. The interrogation was recorded on audio and video and played for the jury at trial.

Following are excerpts from the transcript that Blackwell quoted in the opinion.

Detective: “Do you want to waive your Miranda rights and let us tell you what this is about?”

Defendant: “Do I want to waive my rights? No.”

Detective: “You don't? So you don't know what it's about?”

Defendant: “I'm not waiving nothing.”

Blackwell's 22-page opinion had a lot to say in footnotes.

“We note that, in this case, not only would a reasonable police officer have understood Grant to have invoked his right to remain silent, but the record shows that the police officers conducting the custodial interrogation of Grant actually understood that he had done so yet continued to badger him to change his mind,” Blackwell said in footnote 8.

But it is Blackwell's footnote 9 that the defense attorney, Goldberg, said goes to the heart of the case. The footnote takes up nearly an entire page. “On appeal, the prosecution has continued to urge (as it did in the trial court) that the investigators were not obligated to respect the invocations of the right to remain silent until they had satisfied themselves that Grant understood those rights, and they could satisfy themselves only by reading the Miranda warnings. To begin, it was the investigators who first made reference to 'Miranda,' Grant unequivocally said that he understood his 'Miranda rights' in response to that reference and prior to the reading of the Miranda warnings, and he said nothing that gave reason to doubt that he understood the nature of his right to remain silent.”

Blackwell went on to say that police had no excuse to believe Grant didn't know what he meant when he said he had nothing to say. “Nor is it surprising that an ordinary citizen might know of his 'Miranda rights' prior to the reading of Miranda warnings; the warnings are now deeply ingrained in our popular culture,” Blackwell said. “More important, however, the Miranda warnings are a shield for persons in police custody … The warnings are not a sword for the police, a means for police to deny the right of a citizen to remain silent.”

Blackwell went on to say that, even after officers had “broken the will to resist Interrogation,” still Grant “again unequivocally invoked the right to remain silent after the Miranda warnings were read.”

Goldberg said the opinion leaves little for the prosecutors to use in a retrial.

“The Supreme Court repeatedly, and appropriately, referred to the evidence against Mr. Grant as 'weak,' even inclusive of the 'arguably incriminating' statement that he made to law enforcement,” Goldberg said. “The State's evidence against Mr. Grant now consists solely of his 'mere presence' at the scene of the crime and 'mere association' with the actual perpetrator of the crime, which in and of itself is legally insufficient to convict someone of a crime.

Goldberg added that the court's “reminder to prosecuting attorneys about their duty to seek justice, when discussing the violation of Mr. Grant's rights, applies with equal force to continued prosecution of someone when the evidence against them objectively and legally demands otherwise.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

A Plan Is Brewing to Limit Big-Dollar Suits in Georgia—and Lawyers Have Mixed Feelings

10 minute read

On The Move: Kilpatrick Adds West Coast IP Pro, Partners In Six Cities Join Nelson Mullins, Freeman Mathis

6 minute read

Did Ahmaud Arbery's Killers Get Help From Glynn County DA? Jury Hears Clashing Accounts

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250