Valdosta Jury: Ex-Prison Guard Illegally Fired for Blowing Whistle on Sting Operation

Former Valdosta State Prison Corrections Captain Sherman Main was fired after complaining about being ordered to give cellphones to a prison snitch, who was subsequently stabbed.

October 26, 2018 at 12:00 PM

6 minute read

A Valdosta jury found a former prison corrections officer was fired in retaliation after he objected to being ordered to provide cellphones to a prison snitch as part of a sting operation to catch dirty guards—a scheme that ultimately got the inmate stabbed.

The jury only ruled that the state Department of Corrections violated Georgia's whistleblower law. The amount of damages former corrections Captain Sherman Maine will receive will be decided during a bench trial.

Plaintiff's lawyer Trent Coggins of Trent L. Coggins said the bench trial has not been scheduled. Coggins said he will seek back and front pay as well as lost retirement benefits for Maine, plus attorney fees and expenses.

Coggins noted the trial was delayed for a couple of days by Hurricane Michael, which “pretty much destroyed” the law office of co-counsel Douglas McMillan of Shingler & McMillan in Donalsonville.

“We kind of agreed that, because of the length of the trial, we'd take a break and come back,” Coggins said.

The Department of Corrections is represented by Senior Assistant Attorney General Laura McDonald and Assistant AG Courtney Poole. The AG's office did not respond to a request for comment.

According to Coggins and court filings Maine, now 46, began working as a corrections officer in 2001, and rapidly rose to the rank of captain at Valdosta State Prison.

In 2010, DOC's internal affairs unit hatched a plan to place an informant in the prison as part of investigation into corrupt prison staff.

“They were looking for dealings between officers and inmates—whatever they could find,” Coggins said. “They told my client that they'd done it elsewhere and been successful, and that it had led to several arrests at Reidsville.”

The state conceded as much, Coggins said.

“Where the stories part ways is that we claimed—and the jury found—that he was ordered to give cellphones to the snitch by the warden and internal affairs officer,” said Coggins, so he could contact the investigating officers.

“They finally acknowledged that the plan to put the informant in the prison was theirs, but they claimed that no one ever told my client to give him the cellphones,” said Coggins. “They said he was supposed to procure them from other inmates.”

According to defense testimony, the informant was supposed to barter items like potato chips and Honey Bun pastries for the phones, Coggins said.

“There was ample testimony that cellphones were prevalent in the prison but that they cost between $300 and $1,000,” said Coggins. “I don't think it made any sense to the jury that he was supposed to get them for Honey Buns.”

Maine, who had previously been a supervisor with the Correctional Emergency Response team, which deals with contraband, hostile inmates and emergency situations, knew that giving an inmate a cellphone was illegal.

He also was concerned about the informant's safety and objected to the plan, Coggins said.

Even so, he was ordered on several occasions to provide a cellphone when the previous one was confiscated. There were plenty available, because they are frequently thrown over the prison fences or seized from inmates, Coggins said.

In January 2012, new inmates transferred into the prison recognized the informant—who had served a similar role at another prison—and he was stabbed 19 times, Coggins said.

Maine visited the man at South Georgia Medical Center, where the inmate threatened to sue because he wasn't protected.

“My client went back and said, 'If this thing blows up, I'm not going to cover it up,'” he said.

Maine was placed on administrative leave and became the target of an investigation himself.

Maine wrote to Corrections Commissioner Brian Owens in 2012 to complain about the sting operation and his treatment.

“They eventually came up with some other reasons to fire him, but the main one was that he provided the inmate cellphones,” Coggins said.

According to the defense portion of the pretrial order, Maine was under investigation by the FBI at the time of his termination, and a state internal affairs investigation “found that there was sufficient evidence that [Main] violated the law as well as internal Standard Operating Procedures.”

Maine was fired in 2014, and he sued the following year in Lowndes County.

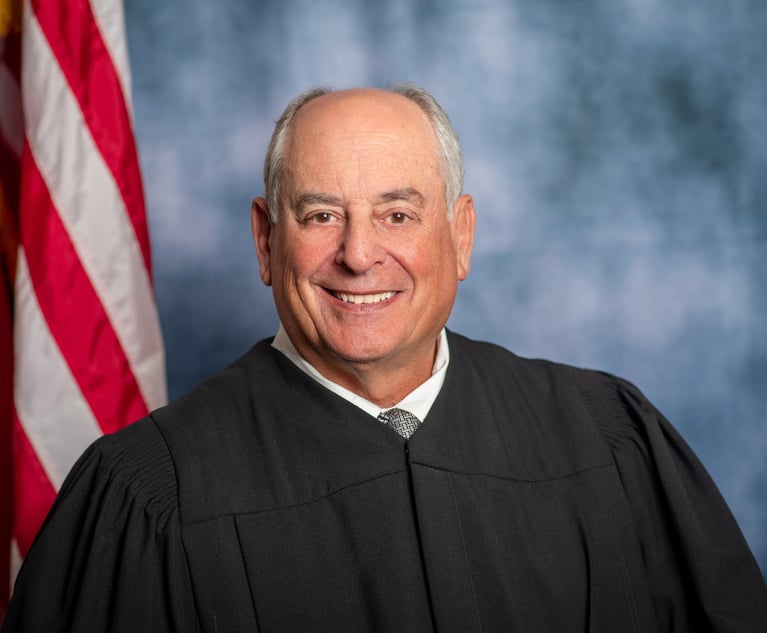

During a superior court trial that began Oct. 8 before Senior Judge Frank Horkan, Coggins said 22 witnesses testified, including Owens and several corrections employees.

No inmates testified, he said, including the informant, who could not be found.

The jury retired to deliberate on Oct. 16 and came back the next day with a plaintiff's verdict.

The three-part verdict form asked whether Maine had reported a violation of the law or regulation when he objected to the use of a confidential informant in 2010, whether he had reported a violation when he wrote to Owens in 2012 and whether the department illegally retaliated against him in violation of the Georgia Whistleblower Act.

The jury affirmed all three sections.

Coggins said the AG's office intends to file a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict.

Maine said he is gratified by the verdict, which confirmed he'd done the right thing, even if it cost his career, Coggins said. Main has since taken up the occupation of tree surgeon.

“He's returned to working in forestry—his previous career was cutting down trees—since he's been blackballed by the law enforcement community,” said Coggins, noting that Maine's Police Officer Standards and Training certification was stripped after his firing.

Coggins said they are discussing whether the verdict means Maine can reapply for his certification.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Appeals Court Removes Fulton DA From Georgia Election Case Against Trump, Others

6 minute read

Family of 'Cop City' Activist Killed by Ga. Troopers Files Federal Lawsuit

5 minute read

Fulton Judge Rejects Attempt by Trump Campaign Lawyer to Invalidate Guilty Plea in Georgia Election Case

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250