Split Court OKs Unsealing Grand Jury Transcript in 1946 Lynching Case

"There is no indication that any witnesses, suspects, or their immediate family members are alive to be intimidated, persecuted, or arrested," Judge Charles Wilson wrote.

February 11, 2019 at 06:01 PM

3 minute read

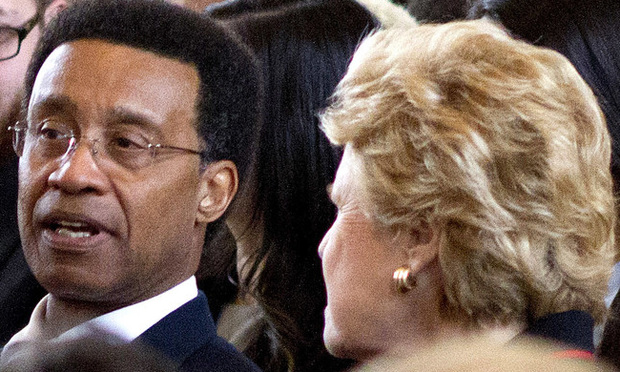

Judge Charles R. Wilson. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Judge Charles R. Wilson. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

A split panel of Atlanta's federal appeals court upheld a judge who ordered unsealing the transcript of a grand jury tasked with investigating the lynching of two African-American couples at Moore's Ford Bridge in 1946.

A federal grand jury charged no one in the mob beatings and shooting deaths of George and Mae Murray Dorsey and Roger and Dorothy Dorsey Malcom. More than 70 years later, historian Anthony Pitch petitioned the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia in Macon to unseal the transcripts, and in 2017, Judge Marc Treadwell agreed.

The U.S. Department of Justice appealed the ruling, and on Monday a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit affirmed Treadwell's ruling. Government lawyers, arguing he abused his discretion by basing his decision solely on the historical significance of the lynching, which drew the attention of President Harry Truman and is considered a precursor to the civil rights movement.

Judges Charles Wilson and Adalberto Jordan held that Treadwell did not abuse his discretion, because the lynching case provided sufficient “exceptional circumstances” to override typical grand jury secrecy.

Wilson wrote for the majority that the case's role in the civil rights movement and the passage of more than 70 years, among other factors, meant that it served as a historically significant exception to keeping the transcripts secret.

“There is no indication that any witnesses, suspects, or their immediate family members are alive to be intimidated, persecuted, or arrested,” Wilson wrote.

Visiting Judge James L. Graham of the Southern District of Ohio, sitting by designation, dissented, writing, “I believe that judges should not be so bold as to grant themselves the authority to decide that the historical significance exception should exist and what the criteria should be.”

He added that descendants of suspects or witnesses could suffer from the release of the transcript. “I am unable to dismiss the reputational harm that could occur to a living person if the grand jury transcripts reveal that their parent or grandparent was a suspect, a witness who equivocated or was uncooperative, a member of the grand jury which refused to indict, or a person whose name was identified as a Klan member,” Graham wrote.

Jordan concurred specially, noting that he'd have decided differently the 1984 Eleventh Circuit case that set out the “exceptional circumstances” standard for unsealing grand jury records. He pointed out that federal judges rejected an effort by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder in 2011 to change grand jury secrecy rules that would have established procedures surrounding unsealing grand jury records.

Bradley Hinshelwood of the Justice Department in Washington argued for the government. A DOJ spokesman said the department declined to comment.

Joseph J. Bell of Rockaway, N.J.'s Bell & Shivas represented Pitch, the historian seeking the records. He said they were “ecstatic” over the ruling, noting that Pitch first sought the records in 2014.

Bell called the ruling “another brick in the emerging wall of justice.”

Bell's practice includes labor and employment law, county and municipal government, civil rights, criminal law, DUI/DWI and tort law. He said he came to represent Pitch, who has written a book on President Abraham Lincoln's assassination, after they met in Washington while Bell was joining the bar to the U.S. Supreme Court.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Apply Now: Superior Court Judge Sought for Mountain Judicial Circuit Bench

3 minute read

A Plan Is Brewing to Limit Big-Dollar Suits in Georgia—and Lawyers Have Mixed Feelings

10 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Public Notices/Calendars

- 2Wednesday Newspaper

- 3Decision of the Day: Qui Tam Relators Do Not Plausibly Claim Firm Avoided Tax Obligations Through Visa Applications, Circuit Finds

- 4Judicial Ethics Opinion 24-116

- 5Big Law Firms Sheppard Mullin, Morgan Lewis and Baker Botts Add Partners in Houston

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250