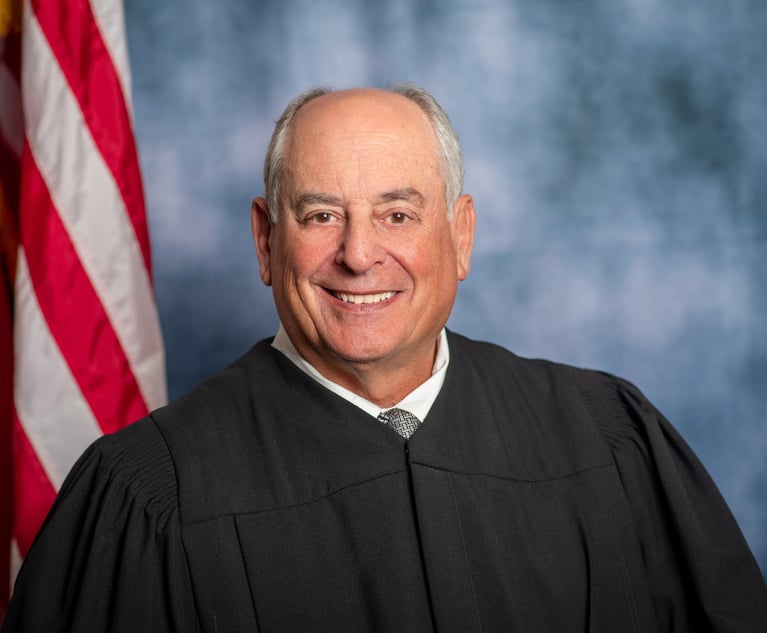

UGA Law Dean Bo Rutledge (left) and Amanda Newton (Photo: John Disney/ ALM)

UGA Law Dean Bo Rutledge (left) and Amanda Newton (Photo: John Disney/ ALM)SCOTUS Loves Arbitration?—It's Not That Simple

Like most conventional narratives (about the court and otherwise), this one contains an element of truth but masks a much more complex, if subtle, pattern in its jurisprudence.

February 14, 2019 at 01:02 PM

6 minute read

Conventional narratives often depict the Supreme Court as displaying an unflinching sympathy for arbitration. Like most conventional narratives (about the court and otherwise), this one contains an element of truth but masks a much more complex, if subtle, pattern in its jurisprudence. Two recent decisions by the Supreme Court—Henry Schein, Inc. v. Archer & White Sales, Inc. and New Prime, Inc. v. Oliveira—magnify this understated, yet critical, distinction.

The Schein Decision

The dispute in Schein arose in the context of two parties who contractually agreed to submit certain disputes to arbitration but disagreed about the arbitrability of a particular dispute. The Schein court was tasked with answering whether the parties' contractual agreement to arbitrate applied to the “gateway question of arbitrability.” In other words, who decides whether the particular dispute is subject to arbitration—the court or an arbitrator?

In 2010, the Supreme Court in Rent-A-Center, West, Inc. v. Jackson applied the Federal Arbitration Act to the gateway question of arbitrability and found that parties could agree to have an arbitrator decide this threshold inquiry. The court relied on its earlier holding in First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, where it found that parties generally presume that an arbitrator, not the courts, will resolve disputes regarding the use of arbitration, absent express contractual language to the contrary.

Despite the court's decision in First Options and Rent-A-Center, some lower courts, including the Fifth Circuit in Schein, found that, where the argument in favor of arbitration was “wholly groundless,” the court could decide the threshold question of arbitrability. The Fifth Circuit rationalized that courts would conduct a more-efficient threshold inquiry and that judicial efficiency outweighed the parties' contractual agreement to delegate arbitrability questions to an arbitrator if the controversy was frivolous.

In the first opinion by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court in Schein rejected the Fifth Circuit's efficiency rationale as “dubious” and admonished it for attempting to “weigh the merits of the grievance.” The court reminded lower courts that they “must respect the parties' decision as embodied in the contract,” especially in light of the express language of the FAA. Doing so put lower courts on notice that the “wholly groundless” exception to the gateway question of arbitrability is not a viable one. More broadly, the decision also furthered the general belief that the court would support parties' agreements to arbitrate.

The Court in New Prime One week after the Court published Schein, it issued its decision in New Prime, Inc. v. Oliveira. In New Prime, the court considered the scope of the 'transportation' exception to the FAA's interstate commerce rule, a hotly-contested issue since the court's decision in Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Adams. The FAA generally requires courts to enforce arbitration agreements involving interstate commerce, but Section 1 of the FAA exempts contracts for transportation employees. The New Prime court found that a truck driver whose contract was structured in a manner similar to an independent contractor was nonetheless considered an employee for the purposes of the transportation exception to arbitration. In other words, the court unanimously found that these independent contractors could not be forced into mandatory arbitration based on the structure of their contracts.

Importantly, the New Prime court found that a court could determine whether the FAA's Section 1 exclusion applied to the dispute, even where the parties' contracting agreement designated an arbitrator to resolve this threshold inquiry. The Schein court had said that courts must enforce a contract delegating “gateway questions of arbitrability” to an arbitrator. Here, however, the court found that, when interpreting a provision of the FAA (rather than a contractual provision as in Schein), the decision is not automatically one for an arbitrator. Put more succinctly, what Jackson and Schein giveth, New Prime taketh a bit away.

The Court's View of Arbitration Moving Forward

Though the Schein and New Prime decisions do not directly contradict one another (nor does New Prime reference Schein), the court's willingness to read the FAA exception broadly in New Prime illustrates the subtle complexity in the Supreme Court's arbitration jurisprudence and belies over-simplistic (if simple) narratives about its pro-arbitration bias. We have been here before. Nearly a decade ago, when decisions like AT&T v. Concepcion caused stirs about the court's supposed pro-arbitration bias, the court also handed down Granite Rock Co. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which reaffirmed a court's power to resolve a dispute over the meaning of a collective bargaining agreement containing an arbitration clause.

As in prior eras of this complex jurisprudence, court watchers can expect to await additional signs about another subtlely complex area of the court's arbitration jurisprudence, namely the law applicable to the interpretation of an arbitration agreement. The same month that the court heard oral arguments in Schein and New Prime, it also heard oral arguments in Lamps Plus, Inc. v. Varela.

Lamps Plus presents the question of whether either state law or federal common law—grounded in the FAA—should control the interpretation of arbitration agreements, an issue with vestiges in some of the court's most important modern arbitration decisions like Prima Paint. Quipping during oral arguments that the “FAA is not a suicide pact,” Chief Justice John Roberts (who coincidentally argued First Options when he was a Supreme Court litigator) questioned the applicability of arbitration to class action claims.

Argued the same day as Schein, the Lamps Plus decision is expected shortly. The bar should watch carefully for how the court, in the wake of New Prime, examines the enforceability of an agreement to arbitrate.

Peter B. “Bo” Rutledge is dean of the University of Georgia School of Law, where he holds the Herman Talmadge Chair of Law. A former clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Rutledge pursues teaching and research of international dispute resolution, arbitration, international business transactions and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Amanda W. Newton is a third-year law student and research clerkship and merit scholarship recipient at the University of Georgia School of Law. In addition to serving as a research assistant for the dean of the law school, she is a member of the executive board on the Journal of Intellectual Property Law, a representative on the Honor Court and a dean's ambassador.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Fulton Jury Returns Defense Verdict After Pedestrian Killed by MARTA Bus

8 minute read

'The Best Strategy': $795K Resolution Reached in Federal COVID-Accommodation Dispute

8 minute read

Population and Caseload Boom Birth New West Georgia Judicial Circuit

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Call for Nominations: Elite Trial Lawyers 2025

- 2Senate Judiciary Dems Release Report on Supreme Court Ethics

- 3Senate Confirms Last 2 of Biden's California Judicial Nominees

- 4Morrison & Foerster Doles Out Year-End and Special Bonuses, Raises Base Compensation for Associates

- 5Tom Girardi to Surrender to Federal Authorities on Jan. 7

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250