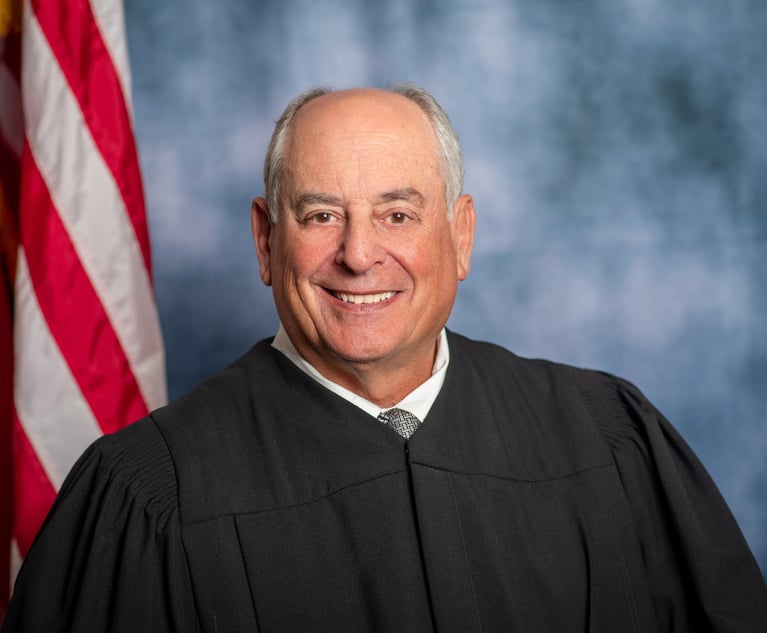

Emmet Bondurant, Bondurant Mixson Elmore, Atlanta. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Emmet Bondurant, Bondurant Mixson Elmore, Atlanta. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)Bondurant Returns to US High Court in Gerrymandering Case

Atlanta lawyer debated Justice Samuel Alito, while comments by Justices Gorsuch and Kagan exemplified the divide.

March 26, 2019 at 03:26 PM

6 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

Atlanta lawyer Emmet Bondurant, who won a key voting rights case in the U.S. Supreme Court 55 years ago, was back before the justices Tuesday, arguing that a gerrymandered redistricting map in North Carolina had gone too far in favoring Republicans.

Near the end of Bondurant's 20-minute presentation, Justice Samuel Alito pressed the lawyer to concede that, under his theory, countless redistricting fights would end up in court. “Even if the map provides only a very small partisan advantage, that would be subject to challenge in litigation,” and “judges are going to have to decide what's the right answer,” Alito said.

Bondurant, the 82-year-old name partner of Bondurant, Mixson & Elmore, responded: “Quite the contrary.” He noted two cases in which the high court held “the legislature can't put its thumb on the scale and pick winners and losers, dictate electoral outcomes, favor or disfavor a class of candidates.”

“That is a standard that can be understood,” Bondurant added. “That is a standard that legislators will obey. And that is a standard that will reduce, not increase, litigation.”

Overall, the justices appeared just as divided as it did a year ago over how to rein in excessive partisanship in redistricting, and nowhere was that more clear than in how Justices Neil Gorsuch and Elena Kagan reacted to each others' comments.

In Rucho v. Common Cause, North Carolina's Republican-controlled General Assembly intentionally drew district lines to preserve its 10-3 dominance of the state's congressional delegation, even though Republicans captured just 53 percent of the statewide vote in 2016. A three-judge district court said the map was an impermissible partisan gerrymander.

But, as the justices struggled during oral arguments with various tests for rooting out excessive partisanship, Gorsuch suggested that states themselves, through independent redistricting commissions, may be on the way to solving the problem.

“One of the arguments that we've heard is that the court must act because nobody else can as a practical matter,” Gorsuch told Kirkland & Ellis partner Paul Clement, counsel to the General Assembly. “I just happen to know my home state of Colorado this last November had such a referendum on the ballot that passed overwhelmingly, as I recall.”

Gorsuch continued: “I believe there are others and I'm just wondering, what's the scope of the problem here? I also know there are five states with only a single representative, right, in Congress, so presumably this isn't a problem there.”

Gorsuch said he sensed “a lot of movement” in the states in this area. Clement quickly agreed, saying, “That's exactly right.” And, he added, Congress also could act. The first bill, H.R. 1. on the agenda of the new Congress, noted Clement, contains a provision to “essentially force states to have bipartisan commissions,” although that may be unconstitutional.

Kagan quickly jumped on Clement's argument that the only constitutionally prescribed way of dealing with redistricting is in the hands of state legislatures, and she tied it into Gorsuch's comments.

“Going down that road would suggest that Justice Gorsuch's attempt to sort of say 'This is not so bad because the people can fix it,' is not so true because you're suggesting that the people really maybe can't fix it,” she said. “So Justice Gorsuch's attempts to save what's so dramatically wrong here, which is the court leaving this all to professional politicians who have an interest in districting according to their own partisan interests, seems to fail.”

In questioning the challengers to the North Carolina plan, Gorsuch also seemed to suggest that they would not be satisfied unless the court required proportional representation, which the court has said the Constitution does not require.

But Kagan didn't see the challengers' arguments that way. “The benchmark is not proportional representation,” she said. “The benchmark is the natural political geography of the state, plus all the districting criteria, except for partisanship.”

The challengers offered more than 24,000 potential redistricting maps for North Carolina, she added, and 99 percent showed that the 10-3 configuration was not the natural one. “It's just not the way anyone can district given the actual political geography on the ground, unless you absolutely try to overrule that political geography,” she said.

Justice Stephen Breyer testifies in 2015. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

Justice Stephen Breyer testifies in 2015. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

Justice Stephen Breyer suggested a way to catch the extreme partisan gerrymanders, a baseline approach, but one that failed to get much traction.

If there is no independent commission, he said, and one party controls the legislature, a gerrymander is unconstitutional if the other party wins a majority of votes in the state, but the party in control gets more than two-thirds of the congressional seats.

In the North Carolina case as well as a second case involving a partisan gerrymander challenge to Maryland's Sixth Congressional District, the challengers offered the high court a number of different tests for weighing partisanship, for example, a three-prong test examining intent, effects and durability of those effects.

In the end, the justices appeared divided along ideological lines in both cases on whether there is a manageable test for determining excessive partisanship and whether the court should be involved at all.

Bondurant was joined by associate Ben Thorpe in representing the challengers to the North Carolina plan. Bondurant shared argument time with Allison Riggs of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. In the Maryland case—Lamone v. Benisek—Maryland Solicitor General Steven Sullivan represented the state; Mayer Brown partner Michael Kimberly was counsel for the challengers.

Jonathan Ringel of the Daily Report added information about Bondurant's argument to this version of the article, which first ran in the National Law Journal.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Georgia Supreme Court Honoring Troutman Pepper Partner, Former Chief Justice

2 minute read

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Appeals Court Removes Fulton DA From Georgia Election Case Against Trump, Others

6 minute read

Family of 'Cop City' Activist Killed by Ga. Troopers Files Federal Lawsuit

5 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250