Beasley Allen Launches Boeing Investigation

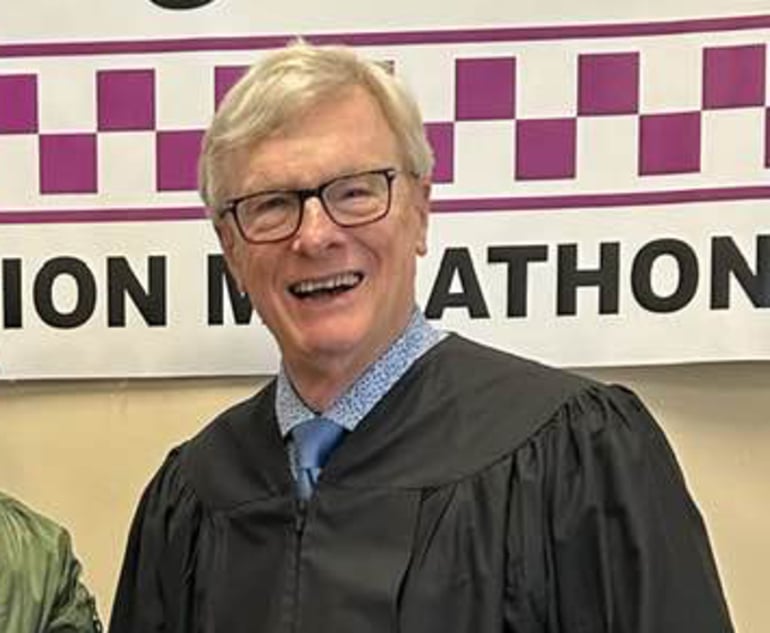

Aviation litigator Mike Andrews of Beasley Allen, the plaintiffs firm in Montgomery and Atlanta, is looking into the Boeing MAX 8 crashes for potential lawsuits.

March 27, 2019 at 02:16 PM

3 minute read

A 737 Max 8 plane destined for China Southern Airlines at the Boeing Co. manufacturing facility in Renton, Washington, U.S., on March 12. (Photo: David Ryder/Bloomberg)

A 737 Max 8 plane destined for China Southern Airlines at the Boeing Co. manufacturing facility in Renton, Washington, U.S., on March 12. (Photo: David Ryder/Bloomberg)

As Boeing Co. unveiled its intended software fix Wednesday for its 737 MAX 8, Beasley Allen of Montgomery and Atlanta announced its own investigation of the crashes involving those aircraft for potential litigation.

Beasley Allen said Mike Andrews, who focuses on aviation litigation, is leading the firm's efforts to investigate the crashes.

“Boeing's conduct was unconscionable and led to the deaths of 346 people,” Andrews said in a news release on the firm website Wednesday. “While Boeing prioritized protecting its profits the company knew that its latest iteration of its 737 aircraft was flawed. It ignored and even tried to cover up the aircraft's deadly problems. Not only is this the basis of possibly hundreds of wrongful death lawsuits, it also prompted an ongoing criminal investigation of Boeing by the U.S. Department of Transportation's Office of Inspector General and the Department of Justice.”

On March 10, Ethiopian Airlines Flight ET302 departed from Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, at 8:38 a.m. local time. The plane was headed to Nairobi, Kenya, when it lost contact with air controllers six minutes later. The crash killed all 189 people on board. Indonesia's Lion Air Flight 610 crashed Oct. 29, also killing everyone on board. The two aircraft were new Boeing 737 MAX 8, and both aircraft experienced the same type of erratic behavior just before they crashed, according to news reports.

Preliminary investigations tie the crashes to an automatic flight-control system called the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, Beasley Allen said. The MCAS was installed after a retrofit to modernize the old Boeing 737 design resulted in a tendency for the plane's nose to pitch up while in flight. The MCAS was supposed to detect that improper pitch and automatically correct to push the nose of the aircraft back down.

News reports suggested that the planes pointed downward soon after takeoff. When pilots react to the sudden downward motion of the aircraft and pull up on the flight controls, the MCAS again falsely senses a nose-up problem and pushes the nose down again, Beasley Allen said. This results in a tug-of-war between the pilot and the flawed MCAS creating an undulating flight path and causing the plane to lose altitude and airspeed.

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg released a statement resolving to find out what happened and why.

“Since the moment we learned of the recent 737 MAX accidents, we've thought about the lives lost and the impact it has on people around the globe and throughout the aerospace community. All those involved have had to deal with unimaginable pain. We're humbled by their resilience and inspired by their courage,” Muilenburg said. “With a shared value of safety, be assured that we are bringing all of the resources of The Boeing Company to bear, working together tirelessly to understand what happened and do everything possible to ensure it doesn't happen again.”

Muilenburg added, “We are all humbled and learning from this experience.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Carrier Legal Chief Departs for GC Post at Defense Giant Lockheed Martin

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250