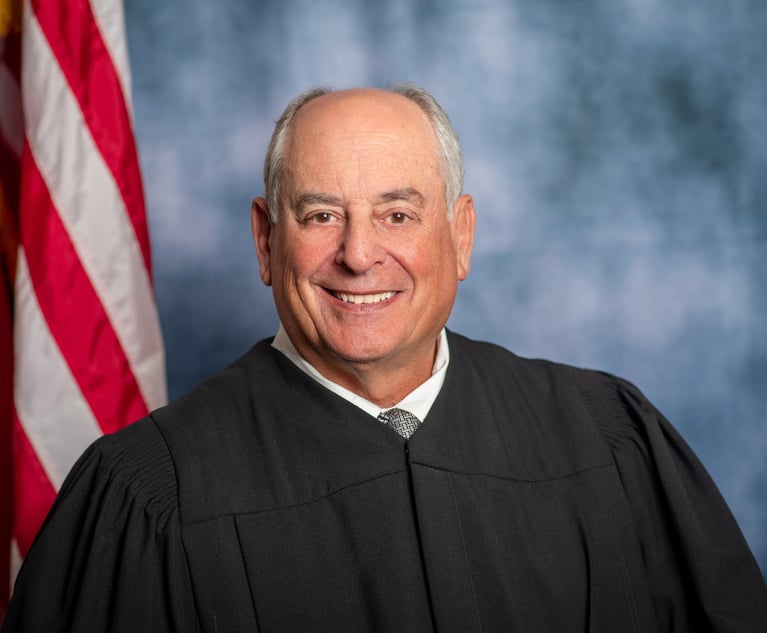

Lance Cooper (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Lance Cooper (Photo: John Disney/ALM)Sparks Fly Following $13M Valdosta Verdict

Defense attorney Steven Kyle of Bovis, Kyle, Burch & Medlin accused plaintiffs counsel Lance Cooper of the Cooper Firm of violating a confidentiality agreement by talking about the case. Cooper called that an unconstitutional effort to place a gag order on the record of a public trial.

August 06, 2019 at 02:45 PM

9 minute read

A $13 million verdict and a high-low deal erupted into a posttrial feud in Lowndes County State Court.

Less than a week after the trial, the defense lawyers asked the judge to sanction the plaintiffs lawyers for talking about it, alleging a “blatant violation” of a confidentiality agreement. The plaintiff’s team called that a “bizarre” attempt to “twist” a private high-low pact into a gag order on widely known facts in the public record.

The specially set, two-week trial in Valdosta before Chief Judge John Kent Edwards started July 15. It was Anthony Ugalde’s day in court in his lawsuit against the owner of a paper mill where he suffered severe chemical burns nearly five years earlier, when he was 21.

Ugalde’s legal team included Lance Cooper and Andrew Ashby of the Cooper Firm in Marietta, along with Charles Shenton of Young, Thagard, Hoffman, Smith, Lawrence & Shenton in Valdosta.

The mill’s owner, Packaging Corp. of America, was defended by Steven Kyle and William Davis of Bovis, Kyle, Burch & Medlin in Atlanta. PCA is a publicly traded company based in Lake Forest, Illinois. The mill where Ugalde was burned makes linerboard for cardboard boxes. It’s in Clyattville, just outside of Valdosta, and is one of the leading employers in the area, according to the Valdosta-Lowndes County Development Authority.

The story told in court documents prepared by his lawyers said Ugalde went to the mill working for a contractor doing maintenance and cleaning on the equipment. He had been wearing a protective suit but had removed it after lunch when a mill maintenance employee watching the work said he didn’t need it anymore. He had one last bolt to remove so they could take the lid off a chemical tank. When he loosened the bolt, between 200 and 500 gallons of hot chemicals came shooting out onto him, pinning him against a scaffold railing. Eventually, he was able to push back and jump off the scaffolding. But the damage was done. He was airlifted to Shands Hospital in Gainesville, Florida, where he remained in a coma for two weeks. Even now, he has permanent scarring over more than half his body.

The mill’s lawyers argued that the company wasn’t to blame, and that Ugalde wouldn’t have been hurt if the contractor had provided proper supervision and made sure he kept wearing his protective suit, according to court documents.

The jurors returned a $13.35 million verdict on July 25. They apportioned fault three ways: 2% to Ugalde, 24% to the contractor that brought him to the mill, and 74% to the mill’s owner, PCA.

Six days later, on July 31, PCA’s lawyers filed a motion for sanctions against Ugalde’s lawyers, alleging violation of a confidentiality agreement.

Kyle said he couldn’t discuss the case because of the confidentiality agreement or discuss the confidentiality agreement itself.

But he spelled out the defense’s position in the four-page motion for sanctions, starting with the revelation that the parties had entered into a high-low agreement before the judge on July 24, the day before the verdict. The money was to be paid within 21 days.

“Certain confidentiality arrangements were part of the agreement, memorialized as follows before the Court,” the motion said. It included a partial transcript of the lawyers talking to the judge.

“Under confidentiality light, there can be no mention of parties or any mention of a—the location of Valdosta, Georgia, or a paper mill in Valdosta, Georgia, Lowndes County, so that you can identify this particular location,” Kyle said.

The judge said he understood and asked if opposing counsel agreed.

“Yes, Your Honor,” Cooper replied, according to the motion.

“The plain purpose and intent of this confidentiality agreement was to prevent Plaintiff or Plaintiff’s counsel from publishing or otherwise calling attention to the identity of the parties or the location where the plant was situated i.e. Valdosta Lowndes County Georgia,” Kyle said in the motion for sanctions. “While the verdict itself is a matter of public record, by virtue of the confidentiality agreement the Plaintiff and his counsel agreed not to publish, call attention to, or otherwise participate in the dissemination of the identity of the parties.”

But, Kyle alleged, “on or about July 29, 2019, a ‘press release’ was found on the website for Mr. Ugalde’s attorneys.” That reference was to the Cooper Firm website, which includes a blog and news about cases.

Kyle’s motion said the Cooper Firm’s release “indicated, inter alia, that PCA had ‘destroyed’ evidence.” The press release also “specifically identified both Ugalde and PCA by name” as well as the plant in Lowndes County. Kyle even quoted the release saying the verdict was “the largest verdict ever returned in Lowndes County.”

“It is unknown how long this press release was available on Plaintiff’s counsel’s website, what media outlets it was sent to or what other social media sources it may have been posted to on the internet,” Kyle’s motion said. “The self-created press release is a flagrant violation of the confidentiality agreement which was stated on the record before the Court.”

Kyle and Davis asked the judge to order Cooper to remove all published statements regarding the identities of the parties. They also asked the judge to “examine counsel for the plaintiff under oath” and to examine the now-disappeared release.

They asked the judge to “affirmatively request that any persons or entities who have copied or re-posted any original information disseminated by the Plaintiff or his counsel be required to remove / take down that information.”

One more request: “Award a monetary sanction as the court deems just and proper for this blatant violation.”

Cooper told the Daily Report that he didn’t think it would be appropriate for him to discuss the sanctions motion or the confidentiality agreement—“given the status.”

But he filed a 14-page response on Friday arguing against the other side’s “bizarre” assertions.

“PCA’s motion attempts to take confidentiality to a level rarely seen, all while relying on an interpretation of ‘confidentiality’ that courts and State Bars have routinely rejected as impermissible and unethical. Nevertheless, PCA filed a terse and baseless motion relying upon that interpretation, seeking ‘sanctions’ for the purported ‘violation’ of a private high-low agreement. But no violation ever occurred,” Cooper’s response said.

“Mr. Ugalde and his counsel take seriously the agreement they entered into and would never violate any portion of it,” Cooper continued in his response. “PCA’s motion amounts to little more than its attempt to twist the agreement’s generic confidentiality language into something it is not, never was and never could be. As everyone understood the agreement—entered into before PCA received the jury’s verdict—PCA’s ‘confidentiality lite’ applied to the high-low agreement itself. Because that is the only thing that it could apply to.”

Cooper argued that the PCA team is attempting to “prohibit Mr. Ugalde or his counsel from ever speaking about facts that have been publicly disclosed in open court and are matters of public record.”

What the PCA lawyers seek amounts to “a court-enforced gag order, or a nondisclosure provision”—which they never asked for and couldn’t have received, Cooper’s response said. Such an order would be an “unconstitutional prior restraint,” it said, and it would prevent Ugalde from talking about the case with his own mother, who sat through the trial.

The response pointed out what it cast as a contradiction in trying to keep a dispute private once it goes to court.

“Disregarding the candid advice of Mr. Ugalde’s counsel, the mediator, and everyone else involved in the lawsuit, PCA refused to settle this case and, as a result, got the trial and jury verdict that they bargained for. Now that PCA obtained the result that everyone warned them about, PCA wants to improperly, and unlawfully, prevent Mr. Ugalde and his counsel from discussing the public facts of the trial in any meaningful way,” Cooper said in his response.

“Mr. Ugalde respectfully requests that this Court put this issue to bed once and for all, and rule that the bargained-for confidentiality relates not to public facts that are the matter of public record, but only to private facts that PCA has shown at least some desire to keep secret, namely the portions of the high-low agreement deemed confidential by PCA,” Cooper concluded in his response.

Kyle and Davis filed a reply brief disputing Cooper’s claims, calling them “hypothetical musings” and “typical trademark quip” accusations.

“In every jurisdiction in the United States of America, a client may request that his attorney to refrain from disclosing even publicly available information about a case, and a lawyer should abide by that request,” the defense reply brief said. “It is the private character of this agreement—consent to which was given freely by the private parties thereto—that is important. Plaintiff’s counsel’s musings about ‘prior restraint’ and deprivations of Constitutional rights are inapplicable, since no government agency took action which deprived anyone of a right. Instead, the private parties entered into a private agreement—which is perfectly acceptable under Georgia law.”

While Cooper didn’t comment on the confidentiality dispute, he did talk about his client.

“We’re grateful to have had the opportunity to represent Anthony,” Cooper said. “He’s a wonderful young man and very deserving.”

The case is Ugalde v. Packaging Corporation of America, No. 15SGV0243. Records are posted on the Lowndes County Odyssey Portal.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Fulton Jury Returns Defense Verdict After Pedestrian Killed by MARTA Bus

8 minute read

'The Best Strategy': $795K Resolution Reached in Federal COVID-Accommodation Dispute

8 minute read

Population and Caseload Boom Birth New West Georgia Judicial Circuit

7 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250