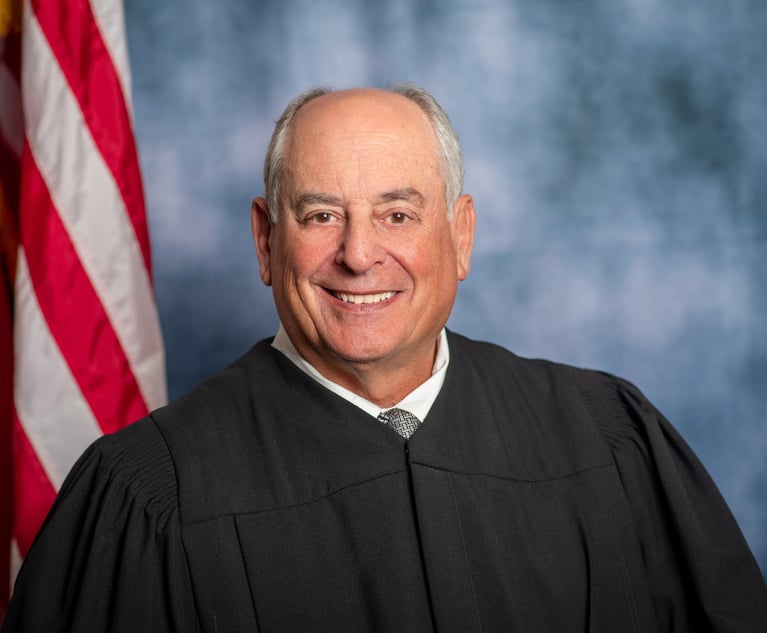

DeKalb County Judge Clarence Seeliger (Photo: (Zach Porter/ALM)

DeKalb County Judge Clarence Seeliger (Photo: (Zach Porter/ALM)After 40 Years on the Bench, Judge Tells What 'Finally Got to Me'

Judge Clarence Seeliger will leave his job open in the 2020 election. He won his way onto the bench in 1980, beating an incumbent known for jailing Martin Luther King Jr. on a traffic ticket and flying a Confederate flag in court. Seeliger became known as a champion of justice for those who had suffered abuse.

October 29, 2019 at 06:06 PM

5 minute read

It's not 40 years on the bench or even turning 80 that has Judge Clarence Seeliger feeling ready to retire when his current term on the DeKalb County Superior Court ends on Dec. 31, 2020.

And it's not the murder cases, he said Friday morning just before returning to the bench to preside over yet another one of those.

"What gets to you is the custody cases," the judge told the Daily Report. "They can be really wearing."

And they've changed dramatically during his career in ways that make them harder for everyone, he said.

"It finally got to me," he added.

Seeliger announced this month that he will not seek another term in 2020 but will instead leave his seat open for others to run. The nonpartisan election will be held with the primaries May 19.

A Seattle native, Seeliger went to the University of Washington, where he earned a political science degree in 1963. He followed that with military service, earning the rank of captain. Then he moved to Atlanta to attend law school at Emory University, where he earned his J.D. in 1970.

He practiced privately for a decade. During that time, he saw a certain judge on the DeKalb State Court abuse one of his clients. The same judge had jailed Martin Luther King Jr. on a minor traffic violation a few years earlier and kept a Confederate flag displayed in his courtroom. In 1980, Seeliger ran for the judge's seat and won.

The first things Seeliger did were remove the Confederate flag and hire the first African American bailiff to serve that court. Four years later, he ran for and won a seat on the DeKalb County Superior Court.

Over the years, the judge proved to be a strong supporter of civil rights and justice for those who had been mistreated. He helped draft the law giving the first guidance for how to write a protective order for the safety of survivors of domestic violence. Former Gov. Zell Miller appointed him a member of the Georgia Commission on Family Violence. The Decatur-based Women's Resource Center to End Domestic Violence created a justice award with his name on it.

So when Seeliger talks about family law, it is with a depth of experience. He estimated that 45% of his caseload is family law. Criminal cases take up about half of his time. Civil cases—the ones that are "interesting, challenging" and "make us want to be a judge"—make up about 5%.

Those domestic cases—particularly the custody disputes—mirror the changes in the world around them, he said.

Custody cases 40 years ago involved married couples in the process of divorce, with lawyers on both sides. "It was easier," he said. "Now, 60% of domestic relations parties were never married."

Often the cases involve fathers seeking to legitimate their offspring, gain rights to visitation and even custody, he said. "The parties have not lived together. The child might have been [born] of a one-night stand. They don't have any loyalty to each other, but they are both responsible for this child," Seeliger said.

Most of the litigants in family cases can't afford an attorney and proceed pro se.

"It puts me in the situation of trying to act as a kind of a lawyer for both people, but I can't get directly involved," he said.

Lacking legal counsel, the parties have less restraint in their mutual desire to "castigate their partner," Seeliger said.

"Their idea of a courtroom is 'Judge Judy'—where people stand up and scream at each other," he said. "That doesn't help me."

The saving grace—if there is any in this situation—comes from mediators, who can sit down and explain "how important it would be for the parties to work it out," Seeliger said. And guardians ad litem are the heroes, volunteering their time to investigate and advocate for children, he said.

"Guardians ad litem help a great deal," Seeliger said. "Most of them are lawyers." (His go-to source is the DeKalb Volunteer Lawyers Foundation.)

Still, Seeliger admitted he will miss his job.

"I love being in the courtroom," he said. "I'm looking around for things to do."

He said he hopes to travel with his wife of 50 years, Gwen Hagler Seeliger. They have two daughters and three grandchildren.

He's looking into increasing his activities with Christ Episcopal Church, where he teaches Sunday School. He may pick up the pace on his three-times-a-week lap swimming. And he plans to offer his services as a senior judge.

"That's in the hands of the judges," he said. "If they need me, they'll call me."

When he announced his retirement plans, Seeliger said simply, "I have been honored to serve."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Georgia Supreme Court Honoring Troutman Pepper Partner, Former Chief Justice

2 minute read

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Appeals Court Removes Fulton DA From Georgia Election Case Against Trump, Others

6 minute read

Family of 'Cop City' Activist Killed by Ga. Troopers Files Federal Lawsuit

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Tensions Run High at Final Hearing Before Manhattan Congestion Pricing Takes Effect

- 2Improper Removal to Fed. Court Leads to $100K Bill for Blue Cross Blue Shield

- 3Michael Halpern, Beloved Key West Attorney, Dies at 72

- 4Burr & Forman, Smith Gambrell & Russell Promote More to Partner This Year

- 5Sanctions Order Over Toyota's Failure to Provide English Translations of Documents Vacated by Appeals Court

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250