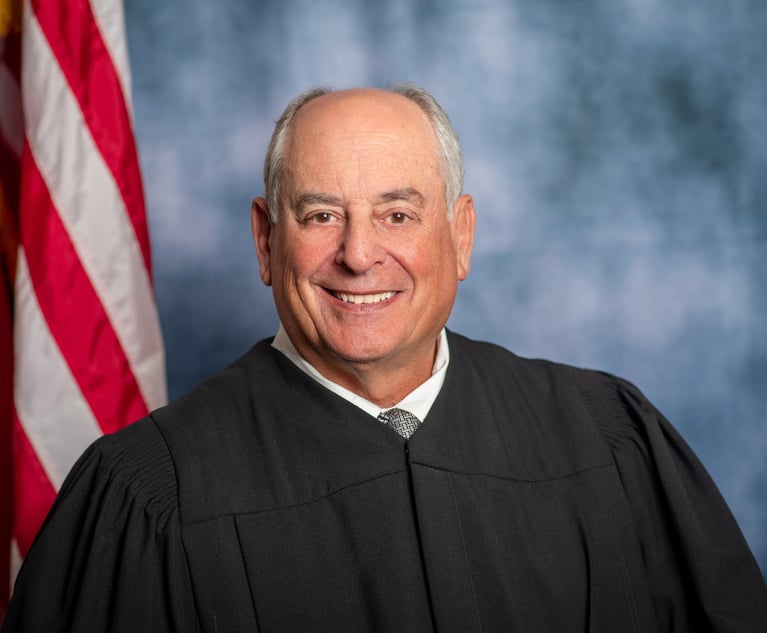

Justice Sarah H. Warren, Supreme Court of Georgia. (Photo: John Disney/ ALM)

Justice Sarah H. Warren, Supreme Court of Georgia. (Photo: John Disney/ ALM)Georgia Supreme Court Upholds Ruling Affirming Lt. Governor's 2018 Election

In a unanimous ruling, the state Supreme Court held that, despite statistical anomalies and a significant undervote in ballots cast for Democratic challenger Sara Riggs Amico, challengers couldn't point to "a sufficient number of specific irregular or invalid votes to change or place in doubt" the 2018 results.

October 31, 2019 at 05:14 PM

7 minute read

The Supreme Court of Georgia has unanimously affirmed the dismissal of a challenge to Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan's election stemming from statistical anomalies in the 2018 election's electronic voting tallies.

In a 94-page opinion authored by Justice Sarah Warren, the high court ruled Thursday that evidence presented at the January trial of an election challenge by Georgia voters and a nonprofit election integrity organization failed to demonstrate that the results of the 2018 contest between Duncan, a Republican, and Democratic opponent Sara Riggs Amico should be invalidated.

The challengers also were unable to point to "a sufficient number of specific irregular or invalid votes to change or place in doubt" the results or establish "sufficient irregularities in the election process to cast doubt" on them, Warren wrote.

"This court has long held that the party contesting the election has the burden of showing an irregularity or illegality sufficient to change or place in doubt the result of the election," she said. "To prevail on such a claim, a party contesting an election must therefore offer evidence—not merely theories or conjecture—that places in doubt the result of an election."

Edward Lindsey, a partner at the Atlanta offices of Dentons who defended the lieutenant governor, said Warren's "detailed and exhaustive opinion" affirms the trial court's order upholding Duncan's election by more than 123,000 votes.

Lindsey contended there was "no actual evidence of hacking or malware impacting the vote count, and the reasons for the difference in voter participation in the lieutenant governor's race and other statewide races were numerous, non-nefarious, and unrelated to the electronic voting system."

"Both the trial court and the Supreme Court found that the plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of presenting evidence that places in doubt the result of the election for lieutenant governor," Lindsey added.

The high court's unanimous decision "should put to rest any unfounded questioning of the accuracy of the 2018 Georgia elections," he said.

More than 3.78 million votes were cast in the race last year, where Duncan bested Amico 51.63% to 48.37%—a difference of 123,172 votes.

But the underlying lawsuit—brought by voters in Fulton and Morgan counties, a Libertarian former candidate for secretary of state, and the nonprofit Coalition for Good Governance—contended that the undervote rate in Amico's race was 6.5 times greater than in the governor's race. The suit also said the electronic undervote appeared to impact Democratic-leaning counties more heavily than Republican-leaning counties and was not similarly reflected in about 250,000 paper ballots also cast in the race.

Amico also received far fewer total votes than all other down ballot statewide races, including those for secretary of state, state attorney general, school superintendent, agriculture commissioner and even some local state legislative races, Brown said during oral arguments at the high court last May. Amico is not a party to the case.

In affirming Senior Superior Court Judge Adele Grubbs' decision last January to throw out the election challenge, the high court rejected arguments by Atlanta attorney Bruce Brown that Grubbs unfairly curtailed discovery by the challengers' cybersecurity experts that might have revealed the causes of significant statistical anomalies in the number electronic ballots cast in Amico's race and given them the proof required for a do-over election.

The vulnerabilities to hacking and defects in the machines themselves could only be confirmed by a forensic analyses of voting machines used during the Nov. 8 election, according to Brown. But an effort to review the internal memories of a cross-section of electronic voting machines used in Fulton County failed after Fulton election officials, on advice of the secretary of state's general counsel, refused to provide the challengers' cybersecurity experts with the access they needed to adequately inspect the machines.

Without an inspection of the electronic voting machines, the challengers had no definitive proof to back up the statistical analyses of their experts, Brown contended during oral arguments in May. Georgia's obsolete electronic voting machines have no paper trail that would provide a means of showing whether the ballot tallies were accurate.

Grubbs initially allowed a limited examination of some voting machines, but Fulton County lawyers and counsel for the secretary of state quickly came to loggerheads with the challengers and their cyber experts over how the machines memory banks could be accessed without destroying internal data. Grubbs also limited discovery to three business days.

During oral arguments, justices questioned whether the challengers were given sufficient discovery. But Warren's opinion said that, given statutory mandates in the state election code regarding an expedited time frame for challenges and the broad discretion of trial judges to control pretrial discovery, "We cannot say the trial court abused its discretion."

The high court also held that, although the challengers complained that the limited discovery Grubbs initially allowed was either insufficient or "not offered in a sufficient form," they "did not heed the trial court's repeated admonition to bring discovery disputes to it by phone or email—and did not even accept the [electronic voting machine] inspection that was offered to them."

The court rejected as "unavailing" claims that the election challengers' refusal "to power up" voting machines prior to any cyber inspection or analysis was based on concerns that doing so would alter the machines' electronic memories.

Brown said during oral arguments the ruling will shape how future election contests based on electronic voting will be litigated. On Thursday, he said the decision "underscores the fundamental problem with electronic voting."

"If a defect in the machines or software causes an incorrect election result, Georgia citizens have little or no practical or effective recourse. With electronic voting, whether on the old system or the new system that the State is deploying for the 2020 elections, there are no verified ballots to recount and, with this decision, citizens have no practical ability to inspect the electronics in discovery in a state court election challenge."

Brown, who also represents the coalition and one set of Georgia voters in an ongoing federal case that would force the state to use paper rather than electronically cast ballots in all future elections, also observed, "It is even more clear today that the only way to protect the constitutional rights of Georgians to vote and to have their votes counted is to use hand-marked paper ballots, which can be audited and recounted if necessary. We hope to secure that relief for Georgia voters in our ongoing federal constitutional cases."

Marilyn Marks, executive director of the Coalition for Good Governance, said Thursday that the state Supreme Court ruling "stands for the proposition that voters and candidates cannot access election records to determine whether the reported results were accurate or corrupted by computer errors. They must accept whatever meager crumbs of records that the state wants to give them, without any meaningful scrutiny being permitted."

She said, "We are greatly disappointed for what this ruling means for Georgia's election integrity and fairness."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Georgia Supreme Court Honoring Troutman Pepper Partner, Former Chief Justice

2 minute read

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Appeals Court Removes Fulton DA From Georgia Election Case Against Trump, Others

6 minute read

Family of 'Cop City' Activist Killed by Ga. Troopers Files Federal Lawsuit

5 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250