Equifax Judge Says 'Serial Objector' Ted Frank Put Out Misleading Information About Settlement

Chief District Judge Thomas Thrash of Georgia's Northern District accused Frank of disseminating "false and misleading information" about the terms of the Equifax consumer class action settlement. Frank says he intends to appeal the settlement order.

January 15, 2020 at 07:04 PM

6 minute read

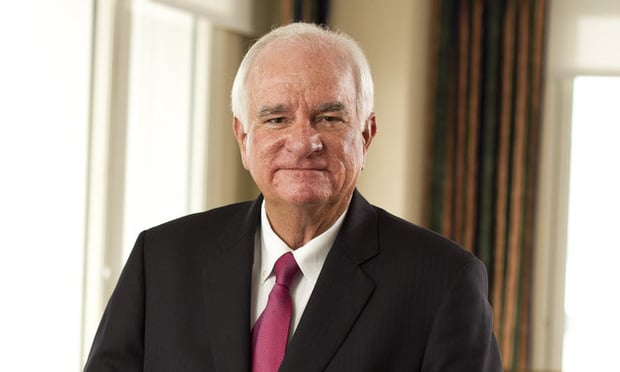

Chief Judge Thomas Thrash Jr., U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Chief Judge Thomas Thrash Jr., U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

The presiding judge in the Equifax data breach multidistrict litigation this week issued a harsh critique of frequent class action critic Theodore Frank, branding him a "serial objector" who "disseminated false and misleading information."

In a 122-page order finalizing the Atlanta-based credit reporting agency's $1.4 billion settlement with 147 million consumers over its 2017 data breach, Chief Judge Thomas Thrash of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia in Atlanta said Frank, director of the Center for Class Action Fairness at the Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute, a nonprofit in Washington D.C., "is in the business of objecting to class action settlements." The judge added Frank's objections in the Equifax case are similar to those he made—and that were rejected—in a data breach case involving the Target Corp.

Thrash said in the Jan. 13 order that, in encouraging others to object to the Equifax settlement, Frank also used a "chat-bot" created by Class Action Inc., "notwithstanding that it contained false and misleading information about the settlement."

Class Action Inc. is a claims aggregator that created a website encouraging people to object based on erroneous information about the proposed settlement, the judge said in his order.

Ted Frank, director, Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute and the Center for Class Action Fairness, at the Federalist Society 2019 Lawyers Convention in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

Ted Frank, director, Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute and the Center for Class Action Fairness, at the Federalist Society 2019 Lawyers Convention in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)Frank said he has "no idea what the judge thinks I said that was false and misleading."

He also said he has "no affiliation" with Class Action Inc. and that "They asked for my help, and I told them their checkbox objection process was unlikely to have any effect, that class counsel would try to strike the objections and that they should forgo working on objections until they could plan ahead far enough in advance to work effectively with an attorney."

In his order, Thrash rejected Frank's characterization of the settlement, finding that the lawyer improperly and dramatically understated its monetary value and disregarded the nonmonetary benefits. Thrash also rejected what he said was the "implication" of some objectors, including Frank, that the recovery from Equifax was inadequate in relations to a possible award at trial.

In a formal objection to the settlement that Frank filed in November, he labeled as "completely fictional" a $380.5 million cash fund to provide consumers with extended credit monitoring, identity protection and repair services, or reimburse them for expenses if their identities were stolen. Frank also contended that counsel representing the consumer class "didn't do any actual litigating in this case" and should be awarded no more than $16.2 million for a settlement he claimed was actually worth no more than $162 million.

"The settlement is at the high end of the range of likely recoveries," Thrash wrote. "Many of the specific benefits of the settlement likely would not be attainable at trial," including the eligibility of all 147 million class members for extended credit monitoring.

The judge also rejected Frank's claim that an additional $70.5 million included in the settlement fund at the request of federal and state regulators did not result from class counsel's efforts.

"This argument fails as a factual matter because it assigns no credit to class counsel's efforts and their agreement to integrate the additional money into the settlement they negotiated," Thrash held. "While regulators may have been the initial catalyst for the extra funds, the money would not have been added to the settlement fund but for class counsel's efforts."

Thrash also disagreed with Frank's attempts to minimize the work of class counsel and his claim that there was little risk in pursuing consumer claims against Equifax. "To the contrary, class counsel faced extraordinary risk, which the objectors unreasonably and erroneously discount," Thrash said.

Frank said he didn't know what Thrash meant in calling him a serial objector or whether it's even a bad thing.

"It's regrettable and highly irregular that the court makes insults that are both untrue and irrelevant" to the settlement," he said.

"My nonprofit and its attorneys have successfully represented class members objecting to abusive class action settlements and certifications for over 10 years," Frank continued. "The court made much of the fact that some of our objections were ultimately unsuccessful, but I'm unaware of any precedent requiring an objector to have a 100% successful track record."

Frank also said that he intends to appeal the settlement's approval.

"I'm happy to let the Eleventh Circuit decide whether we were right on the legal question, and I'm confident that the district court's intemperate language won't poison the well for that appeal," he added.

Frank's objection contended that residents of each state or other jurisdiction that could make separate claims against Equifax under their consumer protection statutes should have been represented by separate counsel.

But Thrash said in his order that Frank's objections, if acted on, "could disadvantage the entire class" and that adopting Frank's proposal would have required at least 34 separate teams of lawyers.

"The selection and appointment process alone would be incredibly time consuming and the duplication of effort involved in ensuring each legal team was adequately versed in the law and facts to assess the relative worth of their clients' claims would be staggering," the judge said.

"Ironically, the same objectors criticize the requested attorneys' fees in this case on the basis that class counsel's hours are inflated because too many lawyers worked on it," Thrash wrote.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

6 minute read

Bass Berry & Sims Relocates to Nashville Office Designed to Encourage Collaboration, Inclusion

4 minute read

Gunderson Dettmer Opens Atlanta Office With 3 Partners From Morris Manning

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250