Lawyers Trade Appellate Arguments Over 'Forced Labor' at Immigrant Detention Site

A key question is whether a federal law prohibiting forced labor applies to private, for-profit prisons.

January 30, 2020 at 06:58 PM

5 minute read

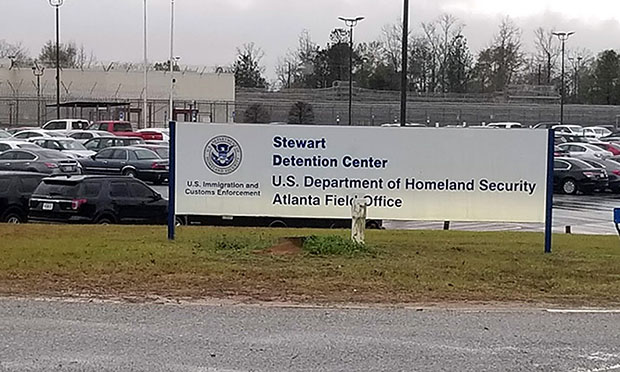

Stewart Detention Center. (Photo: Google)

Stewart Detention Center. (Photo: Google)

Lawyers for a private, for-profit immigration detention center were in a federal appeals court Thursday trying to scuttle a lawsuit claiming detainees were forced to work for a few dollars a day as kitchen and maintenance help and punished if they balked, in violation of a federal law barring coerced labor.

The question before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit is whether a prohibition on forced labor in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act applies to private immigration facilities such as those operated by defendant CoreCivic, which operates the Stewart Detention Center in Georgia.

CoreCivic sought to have the federal claims dismissed in 2018, arguing among other things that Congress did not intend the TVPA to apply to "lawfully held detainees." Judge Clay Land of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia declined to dismiss the case in 2018 but granted CoreCivic's certificate for immediate appeal of the question.

Sorting through the three-way arguments, Eleventh Circuit Senior Judges Frank Hull and Stanley Marcus and visiting Judge Barbara Rothstein seemed reluctant to go beyond the question Land certified, despite the company's entreaties they look beyond the plain language of the law.

"It seems to me the problem you've got is that the text could not be clearer," said Marcus, pointing to the law's decree that "whoever obtain[s] labor or services" through the use of threats or coercion is in violation of the act.

CoreCivic lawyer Nick Acedo agreed but said the court should take into account the context of the work program, which he said is voluntary and similar to work programs at detention facilities going back to 1950, well before the act was passed.

Acedo also argued that Stewart is bound by other standards relating to its treatment of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees, who can be required to do things such as make their beds and keep their living areas clean.

Marcus said that was a different standard than using force or threats of violence to make detainees work. In any case, Marcus said, the TVPA contains no "limiting" language declaring that it did not apply to private detention sites, the crux of the matter at hand.

"The court is not bound by the question certified by the district court," Acedo responded, arguing that there was no indication intended to "criminalize the conditions of detention."

"Any crafty lawyer can come up with an allegation that somehow ties the condition of detention to the TVPA," said Acedo, a partner at Struck Love Bojanowski & Acedo in Chandler, Arizona.

The putative class action claims that conditions at the 2,000-bed facility are unsanitary, overcrowded and "deplorable." The large, open dormitories house as many as 66 people who share bathrooms and showers that have no hot water—and some with no cold water. CoreCivic does not provide necessities such as toilet paper, toothpaste and soap, which must be purchased at the commissary, according to the lawsuit. Those wishing to make a phone call must purchase expensive phone cards.

CoreCivic pays detainees between $1 and $4 a day for jobs like sweeping and scrubbing floors, doing laundry, preparing food and washing dishes. Those who participate are allowed to stay in two-person cells with a bathroom and temperature-controlled shower, among other perks.

The plaintiffs are represented by a cadre of lawyers from the Southern Poverty Law Center, Project South in Atlanta, Burns Charest in Dallas, and the Law Office of R. Andrew Free in Nashville, Tennessee.

Andrew Free began by saying the appeal is not properly before the court to begin with. While CoreCivic filed the appeal seeking to have the court declare that work programs in private, for-profit detention facilities are not subject to TVPA as a matter of law, the plaintiffs are attempting to show that the program as implemented at Stewart is illegal.

Free noted that the Department of Justice's amicus brief itself said the TVPA did not contain any exceptions for private contractors.

Free noted that Congress specifically included language allowing the government to terminate contracts with providers found to have used forced labor to fulfill those contracts.

Work programs in federal detention programs have been authorized for years, he said.

"But here's the thing … you cannot force people detained in immigration custody to work," Free said.

Free answered affirmatively when Hull asked whether the issue before the court is a "pure question of law" and said the court should send the case back to the Middle District

DOJ civil appellate division attorney Brad Hinshelwood said the department didn't take either party's side as to the whether Stewart violated the act. Noting that private contractors run several ICE facilities, Hinshelwood said the DOJ "wouldn't want the court to inadvertently say something" in a ruling that could jeopardize programs around the country.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

A Look Back at High-Profile Hires in Big Law From Federal Government

4 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250