DA to Review 1960 Slaying in Wake of Film About Georgia Civil Rights Lawyers

The film recalls the work of attorneys C.B. King and Donald Hollowell in Jim Crow Georgia.

February 06, 2020 at 06:10 PM

6 minute read

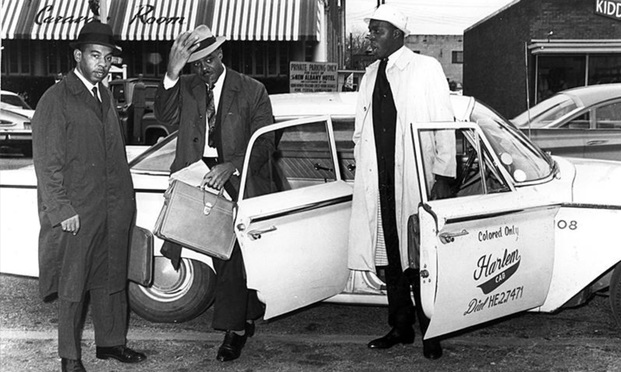

Lawyers C.B. King (from left), Donald Hollowell and Vernon Jordan (Courtesy photo: Clennon King)

Lawyers C.B. King (from left), Donald Hollowell and Vernon Jordan (Courtesy photo: Clennon King)

A district attorney in southwest Georgia is reviewing the 1960 death of an 8-year-old girl in a case that initially led a lawyerless young man to be sentenced to death less than three days after the body was discovered.

R. Victor McNease Jr., the top prosecutor in the Pataula Judicial Circuit, decided to reinvestigate the case after a documentary was released last year about the defendant's 26-month legal fight to win his freedom.

The film, "Fair Game: Surviving a 1960 Georgia Lynching," was made by the son of Albany lawyer C.B. King, who with Atlanta attorney Donald Hollowell saved defendant James Fair Jr. from the electric chair by securing him a new trial. The state, controlled by Jim Crow laws at the time, eventually dropped the charges against Fair, who like King and Hollowell was African American.

The filmmaker sought a new investigation to find the truth about who killed Yvonne Holmes. McNease told filmmaker Clennon King, son of C.B. King, last July that he would review the case for new evidence.

McNease told the Daily Report this week his office doesn't comment on evidence or findings while a case is being investigated or evaluated. He allowed, however, that this case will take longer than a typical one "due to the age of the case and the fact that no one in my office has any personal knowledge of the original investigation and trial."

"Currently, we are collecting and reviewing the original case evidence and court records," McNease added. "Once that phase is complete, we will review any relevant new evidence, if available, and make a decision on how to move forward from that point."

Clennon King's film opens with a black-and-white interview of his father, who died in 1988, saying once black people were subject to lynch mobs but now "they are legitimately taken into the courtroom, and the same end is achieved."

Then it tells of how James Fair Jr., a 24-year-old Navy veteran, joined a friend from New Jersey for a road trip to the friend's home in Blakely, Georgia, on the Alabama border. Blakely is the county seat of Early County, where historians say the second-highest number of lynchings (24) occurred in the state (Fulton County was number one with 37).

The film notes Fair and his friend arrived into town on a Saturday night, May 14, 1960. That same night, the girl's body was found. Fair was arrested at 1 a.m. the next day and accused of raping and murdering the girl. By sundown, he had confessed. On May 16, a grand jury indicted him for rape and murder. On May 17, Judge Walter I. Geer sentenced Fair to death.

The film tells how Fair's mother in New Jersey immediately sought legal help for her son, which she found by way of a late-night radio program in New York that raised $8,000 for defense costs. She hired Nathan Pearlman in New Jersey and King and Hollowell in Georgia. Both were known for their courageous civil rights work.

Rep. Cornelius Gallagher, D-New Jersey, got involved, and in the film he describes a tense meeting when he sought a stay of execution from Georgia Gov. Ernest Vandiver.

Vernon Jordan, then a rookie lawyer working for Hollowell who went on to become a White House adviser and senior counsel at Akin Gump, also appears in the film. His account of how black families fed Fair's legal team "like royalty" when they couldn't go to the whites-only diner across the street from a courthouse is particularly moving.

When a judge in Reidsville dismissed King and Hollowell's petition for a writ of habeas corpus, they went to the Supreme Court of Georgia, where they won a unanimous reversal.

In the decision, Justice Benning Grice noted the record from Fair's appearance in court showed he was offered a lawyer but said he didn't want one—and he wanted to plead guilty and "went into detail as to how he had raped the child and killed her with a pipe."

But during the habeas hearing, Fair testified he told the judge, "I don't want no appointed lawyer" because he wouldn't trust one, according to the high court decision.

"Fair also stated that he did not recall the judge telling him that he could be given the death sentence if he pleaded guilty and that he did not recall telling the judge and others present that he was guilty and describing the crime," Grice wrote. "He did recall signing a paper but stated that he didn't know what it was, that he didn't know anything about law or a court of law."

Writing for the court, Grice held: "Prior to responding to such a charge, any defendant needs capable legal counsel in order to determine such vital questions as whether the indictment is properly drawn, whether the accused has capacity to commit crime, whether the evidence is sufficient to convict and, in the final analysis, whether the defendant should stand trial or appeal to the judge for a lighter sentence. It would be expecting too much of any defendant, alone, to answer for himself such questions as these. No decision made by any person during this life is of greater consequence except a spiritual one to obtain assurance of life hereafter."

"It is clear to us," Grice concluded, "that the lack of time afforded to this defendant, coupled with his lack of counsel, resulted in denial of his constitutional rights to due process and benefit of counsel."

Fair was released more than a year after the high court granted him a new trial when prosecutors said none of the witnesses who'd seen Fair confess were still alive.

"Fair Game" will be shown at Atlanta libraries four times in the next two weeks, and Clennon King will speak after each showing of the 65-minute film. The appearances are 2 p.m. Monday at the Peachtree Branch Library, 6 p.m. Feb. 18 at Metropolitan Branch Library, 6 p.m. Feb. 20 at West End Branch Library and 6 p.m. Feb. 25 at Southwest Branch Library.

King has provided a link to movie to be displayed on the Daily Report's website.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

DC Lawsuits Seek to Prevent Mass Firings and Public Naming of FBI Agents

3 minute read

Apply Now: Superior Court Judge Sought for Mountain Judicial Circuit Bench

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Big Law's Middle East Bet: Will It Pay Off?

- 2'Translate Across Disciplines': Paul Hastings’ New Tech Transactions Leader

- 3Milbank’s Revenue and Profits Surge Following Demand Increases Across the Board

- 4Fourth Quarter Growth in Demand and Worked Rates Coincided with Countercyclical Dip, New Report Indicates

- 5Public Notices/Calendars

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250