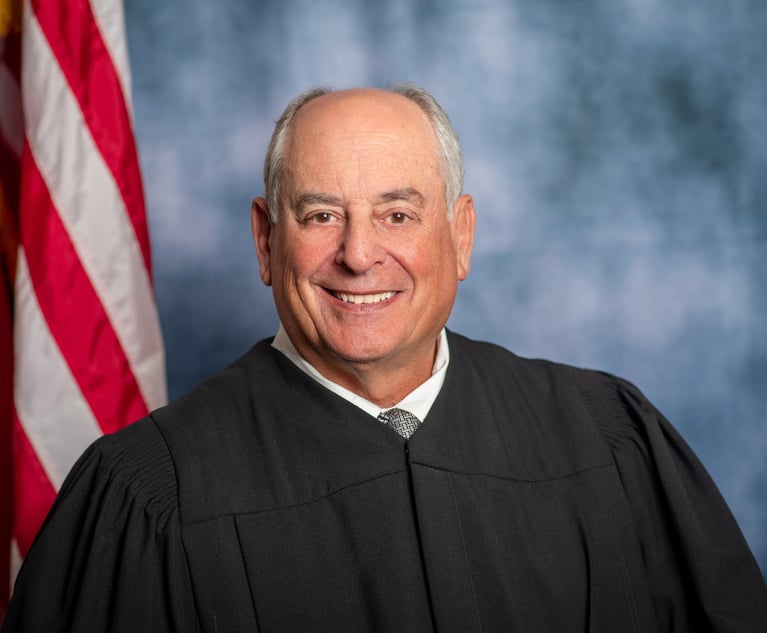

Judge Kathy Schrader, Gwinnett County Superior Court. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)

Judge Kathy Schrader, Gwinnett County Superior Court. (Photo: John Disney/ALM)Gwinnett Judge's Criminal Trial for Computer Theft Powers Up

The discovery of information from Judge Kathryn Schrader's computer on that of a convicted child molester last year spurred her suspension and ultimate indictment, a county prosecutor said.

February 11, 2020 at 04:15 PM

5 minute read

The criminal trial of Gwinnett County Superior Court Judge Kathryn Schrader began Tuesday, with jurors hearing how the judge's bewilderment at repeatedly finding unauthorized documents on her court computer system turned to frustration, then exasperation when county tech staffers were unable to pinpoint her problems.

Schrader ultimately turned to a private investigator, who in turn enlisted a computer expert with a criminal record to install a device to monitor her court computer. Schrader suspected District Attorney Danny Porter and his office were monitoring her computer, her lawyers said.

Schrader's efforts to uncover who might be accessing her computer resulted in her indictment on computer theft charges. Private investigator T.J. Ward, forensic investigator Frank Karic and convicted child molester Ed Kramer were also charged.

But Schrader alone is facing charges now, with Ward, Karic and Kramer all having reached plea deals in exchange for their expected testimony.

Porter and his office recused from Schrader's case and her prosecution is being led by Prosecuting Attorneys' Council of Georgia General Counsel Robert Smith Jr. and staff attorney John Regan.

Regan told jurors that Schrader placed herself above the law and violated rules concerning outside access to county computers and the placement installation of outside software and devices on them without authorization.

Scrader "opened the door to allow information to be taken out" and altered, Smith said.

Schrader's attorney, B.J. Bernstein, countered that the judge "raised legitimate concerns" when she found restricted records from the Georgia Criminal Information Center printed out in her office.

Courthouse techs were "baffled," she said, and continued to offer no explanation when an 18-page police report materialized or when a family member's passport information was printed out.

Schrader also learned that two of Porters' prosecutors were "permissive users" of her computer network, raising concerns that "the state could see her computer," Bernstein said.

"She was a judge, and she was exasperated," Bernstein said.

Schrader knew of Turner as a well-regarded investigator who frequently appeared on CNN, Bernstein said. Turner, in turn, hired Karic and Kramer.

Schrader was told Kramer's name was "Elliott," and the judge no idea the DragonCon co-founder was a convicted child molester, Bernstein said.

Called to testify, Porter related that it was a search warrant served on Kramer's home in Duluth after reports that he had photographed a child in a doctor's office that led to the discovery of the data breach.

Investigators combing through Kramer's computers found data, emails and other materials on Kramer's computer, and a search of his cellphone revealed text messages between Kramer and Schrader.

The district attorney said he initially visited the judge to tell her what was found, because he thought her home network might have been hacked, and offered to have his office's staff inspect it.

"She said she'd think about it, then changed the subject and asked whether I was aware of problems with her computer," Porter said.

Porter said that, when his investigators found data and information from Schrader's network on Kramer's computer, he asked the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to look into the matter.

Bernstein asked why, before her indictment, Porter had requested and been granted a motion recusing Schrader from any of his office's cases.

Porter said he knew Schrader had accused him of tapping her computer.

"You took personal offense?" Bernstein asked.

"To a degree I did, yes," replied Porter. "I mean, nobody likes to be accused of a crime."

Particularly compelling testimony and evidence was offered by GBI special agent Sara Lue, who met with Schrader shortly after Porter asked the agency to investigate.

When Lue showed up at the courthouse and asked to speak with her, a cordial Schrader said she was "relieved" and "glad that I was there from the GBI," Lue said.

"She said she felt like an outsider, like there was some sort of conspiracy against her … She told me she believed her office had been bugged," Lue said.

Schrader told Lue she hired Ward, who connected her with somebody named Elliot to see whether her computer was being hacked and that he had brought in Karic.

The judge said it was only later that she found out Elliott was Kramer, Lue said.

Schrader also gave her a surreptitious cellphone recording of a meeting of Gwinnett County judges held after the breach of the court system was discovered.

The plainly alarmed judges can be heard peppering Superior Court Chief Judge George Hutchinson with questions concerning the scope of the breach, how they should handle it—and who among them had enabled the court's system to be accessed.

Hutchinson dances around the question and says only "that person has not been discharged" when asked.

There's a murmur until someone says "Oooh, I know what's going on."

"Needless to say, I feel Iike I'm being a little mysterious," Hutchinson said.

Lue also produced a thick file folder stuffed with documents and confettied with Post-it notes Schrader gave her, a testament of the letters, emails and pleas she compiled of her efforts to "get someone's attention."

Lue quoted Schrader as saying she had "thought the simplest, most noninvasive thing to do was hire a private investigator."

"I'm a woman of integrity, and I will face the consequences of, you know, getting duped," Schrader told the agent. "I don't know if there are laws against it."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Georgia Supreme Court Honoring Troutman Pepper Partner, Former Chief Justice

2 minute read

'A 58-Year-Old Engine That Needs an Overhaul': Judge Wants Traffic Law Amended

3 minute read

Appeals Court Removes Fulton DA From Georgia Election Case Against Trump, Others

6 minute read

Family of 'Cop City' Activist Killed by Ga. Troopers Files Federal Lawsuit

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'Largest Retail Data Breach in History'? Hot Topic and Affiliated Brands Sued for Alleged Failure to Prevent Data Breach Linked to Snowflake Software

- 2Former President of New York State Bar, and the New York Bar Foundation, Dies As He Entered 70th Year as Attorney

- 3Legal Advocates in Uproar Upon Release of Footage Showing CO's Beat Black Inmate Before His Death

- 4Longtime Baker & Hostetler Partner, Former White House Counsel David Rivkin Dies at 68

- 5Court System Seeks Public Comment on E-Filing for Annual Report

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250