Judge Nixes ICE Detainees' Bid to Be Freed Over Coronavirus Fears

Middle District Judge Clay Land said there were other remedies available to the vulnerable detainees short of being freed from custody.

April 10, 2020 at 05:38 PM

6 minute read

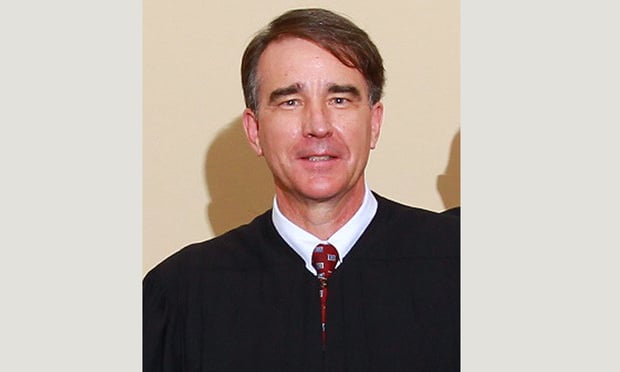

U.S. District Judge Clay Land, Middle District of Georgia. Courtesy photo

U.S. District Judge Clay Land, Middle District of Georgia. Courtesy photo

A federal judge in Columbus turned down an emergency petition asking that eight detainees suffering a variety of health conditions be released from two privately run Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers in south Georgia.

After a two-and-a-half-hour teleconference hearing Friday, Middle District Judge Clay Land denied an emergency habeas petition arguing that the conditions at the Stewart and Irwin detention centers posed such a threat to the detainees' health and lives as to constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

In a written opinion filed Friday afternoon, Land said precedent held that a habeas petition was not the appropriate way to address the detainees' concerns, and that—while there are narrow exceptions to the rule that only release from confinement may remedy such claims—theirs was not among them.

"[I]f the present record supported petitioners' contention that they face substantial risk of serious physical harm and/or death from unconstitutional conditions that cannot be modified to reasonably eliminate those risks, the court may find petitioners' argument for habeas relief persuasive," Land wrote.

"But based upon the present record, the court does not find that the only way to remedy Petitioners' alleged constitutional violations is to release them from custody."

Land emphasized the "narrow scope of today's ruling," and said the petitioners could "amend their motion to seek remedies other than release from detention."

The habeas petition said the detainees at the Stewart County Detention Center, where two detainees have confirmed cases of COVID-19, and Irwin County Detention Center, with one confirmed case, suffer a variety of conditions making them particularly susceptible to the disease, including diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and asthma. Some have histories of repeated medical problems requiring surgical intervention.

Lawyers from the Southern Poverty Law Center, Asian Americans Advancing Justice and Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton filed the emergency petition Tuesday; they have also filed a similar petition in Georgia's Southern District on behalf of three detainees at the Folkston ICE Processing Center.

The Stewart facility is operated by CoreCivic, formerly Corrections Corp. of America; Irwin is run by LaSalle Corrections, and Folkston is a GEO Group facility.

An attorney with the SPLC said the ruling boded ill for detainees at the detention centers.

"These detention centers are ticking time bombs ready to blow if the federal government does not take action immediately," said Rebecca Cassler of the center's Immigrant Justice Project in a statement.

"People are already sick. And between the despicable conditions of these facilities, lack of adequate medical care and the health challenges these people already face, there is little doubt it will soon turn into a complete catastrophe," she said.

The habeas petition said the detainees are being exposed to a potentially deadly disease that even stringent containment measures have failed to contain in the outside world.

"Once a disease is introduced into a jail, prison, or detention facility, it spreads faster than under most other circumstances due to overcrowding, poor sanitation and hygiene, and lack of access to adequate medical services," it said.

"For these same reasons, the outbreak is harder to control," the petition said. "The severe outbreaks of COVID-19 in congregate environments, such as cruise ships and nursing homes, illustrate just how rapidly and widely COVID-19 would rip through an ICE detention facility."

It cited expert advisers from the Department of Health and Human Services, who "describe a 'tinderbox' scenario where a rapid outbreak inside a facility would result in the hospitalization of multiple detained people in a short period of time, which would then spread the virus to the surrounding community and create a demand for ventilators far exceeding the supply."

On Friday Land convened a teleconference hearing, during which he and Kilpatrick attorney Amanda Brouillette grilled the wardens at Stewart and Irwin over their populations, conditions and the procedures they've instituted to safeguard detainees and staff.

ICE and the wardens are represented by the Department of Justice; Amelia Helmick of the U.S. Attorney's Office in Columbus had little to say, maintaining that the court had no jurisdiction to take a decision, such as whom ICE detains, from the executive branch "and replace it with the judgment of the court."

Russell Washburn, who just took over as warden at Stewart, said the population at the 1,900-bed facility is down about 55% to 1,211 detainees.

According to the ICE website, there were two confirmed cases at Stewart, but Washburn said there were five active cases, and that another 30 people were in segregation after having been exposed to those individuals and were being tested regularly.

About 43 are in the high-risk cohort: over 60 years old, or with conditions such as asthma or heart disease.

Washburn said that soap and hand sanitizer was readily available and that the staff was enforcing social distancing requirements 24/7.

Brouillette asked whether that included when detainees slept, asking whether they used bunk beds and, if so, how they were able to stay six feet apart when going to bed or getting up at night.

Washburn said he wasn't certain they had addressed that issue, and Land inquired whether, given the reduced population, it might be possible to alternate beds to maintain the proper distance.

Washburn said he thought so; he also said that all new arrivals are screened on intake for COVID-19 symptoms, and that very few new arrivals are coming in these days.

Warden David Paulk of the Irwin facility said his capacity was 1,296, with a current population of 699, which includes a few county inmates who are housed separately.

Irwin has one confirmed case, he said, while a transport officer has also tested positive for the virus.

Paulk also said his staff was enforcing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, and had been medically screening new arrivals routinely even before the outbreak.

According to its website, ICE began screening detainees in March to identify and evaluate those with a high vulnerability to the disease and had released more than 160 detainees who were older than 60 or pregnant.

It said it is expanding its evaluations to other vulnerable populations, evaluating detainees for release and limiting new arrests. According to the ICE website, the national detainee population dropped by more than 4,000 since March 1.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Fires EEOC Commissioners, Kneecapping Democrat-Controlled Civil Rights Agency

Law Firm Sued for Telemarketing Calls to Customers on Do Not Call Registry

Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

6 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250