Third Circ. Revives Asbestos Claims Against Insurers in W.R. Grace Bankruptcy

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit on Tuesday said that insurers of bankrupt mining company W.R. Grace & Co. could be on the hook for asbestos exposure claims, leaving the issue to a bankruptcy judge to decide.

August 15, 2018 at 04:29 PM

3 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Delaware Law Weekly

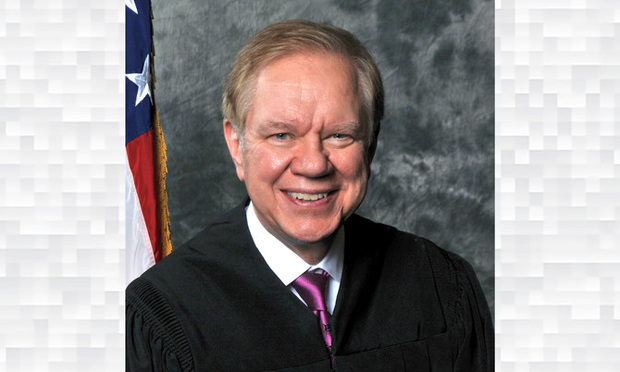

Judge Thomas Ambro of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Judge Thomas Ambro of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit on Tuesday said that insurers of bankrupt mining company W.R. Grace & Co. could be on the hook for asbestos exposure claims, leaving the issue to a bankruptcy judge to decide.

The precedential ruling from a three-member panel of the appeals court revived claims from workers suffering from asbestos-related illnesses, after U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Kevin Gross of the District of Delaware held they were barred by an injunction that channels claims against third parties to a trust.

While the Third Circuit agreed that insurers Continental Casualty Co. and Transportation Insurance Co. were protected by the terms of the channeling injunction, the judges said there remained a question of whether the claims against the insurers, referred to as CNA in the ruling, fit the statutory limitations of U.S. bankruptcy law.

“The proper inquiry is to review the law applicable to the claims being raised against the third party (and when necessary to interpret state law) to determine whether the third party's liability is wholly separate from the debtor's liability or instead depends on it,” Judge Thomas Ambro of the Third Circuit wrote in a 25-page opinion.

Daniel C. Cohn, a partner with Murtha Cullina who argued for the workers, declined to comment. Michael S. Giannotto, a Goodwin Procter partner representing the insurers, did not immediately respond to a call Wednesday seeking comment on the ruling.

The decision, however, gives a second shot to argue in Grace's Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings that the insurers are directly liable for the asbestos-related claims.

On direct appeal, they took the broad view that any misconduct by the insurers exposed CNA to liability. They seized specifically on a group of CNA policies that gave the insurers the right to inspect Grace's facility for asbestos mining and processing in Libby, Montana, arguing that CNA had violated its duty of care to educate and warn workers and their families about hazardous conditions from insufficient dust control at the plant.

CNA, on the other hand, criticized the workers' “per se attempts to hold it indirectly liable” for Grace's conduct. According to CNA, the policy gave the insurers the right—but not the obligation—to inspect the Montana facility and that all responsibility fell on the shoulders of the debtor, whose products had harmed its workers.

Though Ambro sided with CNA on the terms of the injunction, he rejected the statutory interpretations argue by both CNA and the workers, saying “the former is overly narrow and the latter overly broad.” And he directed Gross to review the case under the plain language of the relevant sections of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.

The decision, the judge said, was supported by the purpose of bankruptcy law in the context of asbestos liability.

“The incentive for third parties, particularly insurers, to contribute to an asbestos personal injury trust is their diminished exposure to asbestos liability from the asbestos debtor's conduct or claims against it. Protecting these third parties from derivative exposure resolves lingering uncertainty about their liability and sustains the trust's ability to compensate current and future claimants,” he said.

According to a reliable source, CNA's potential liability could run in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The case is captioned In re W.R. Grace & Co.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Zoom Faces Intellectual Property Suit Over AI-Based Augmented Video Conferencing

3 minute read

Etsy App Infringes on Storage, Retrieval Patents, New Suit Claims

Law Firm Sued for $35 Million Over Alleged Role in Acquisition Deal Collapse

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250