Could Weinstein Accusations Lead to Delaware Derivative Litigation?

Delaware legal observers this week acknowledged the possibility that derivative litigation stemming from damning allegations of sexual misconduct against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein could spill into the Delaware Court of Chancery, which would have jurisdiction over suits involving the Delaware-incorporated company Weinstein helped to found.

October 18, 2017 at 07:13 PM

5 minute read

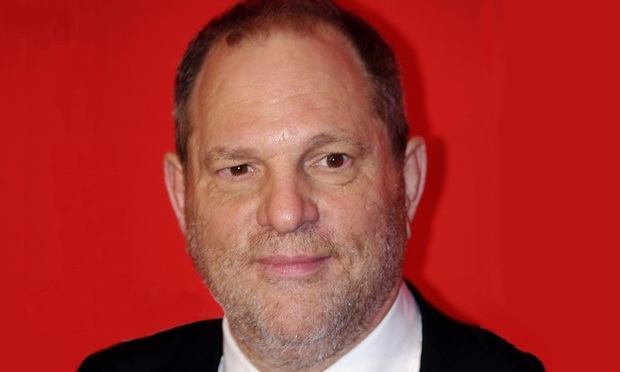

Harvey Weinstein.

Harvey Weinstein. Delaware legal observers this week acknowledged the possibility that derivative litigation stemming from damning allegations of sexual misconduct against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein could spill into the Delaware Court of Chancery, which would have jurisdiction over suits involving the Delaware-incorporated company Weinstein helped to found.

However, critical questions remained regarding Weinstein Co.'s corporate governance structure and the veracity of a yet-uncorroborated media report indicating that the company's board may have known about Weinstein's alleged history of sexual harassment but still worked contractual protections into his 2015 employment agreement.

Multiple attorneys, though, confirmed in interviews that Weinstein Co. board members could potentially be vulnerable to shareholder litigation under the Caremark theory, which exposes directors to liability for corporate harm if they were aware of a systemic problem but failed to act.

“The first thing that comes to mind is Caremark,” said Francis G.X. Pileggi, vice chair of Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott's commercial litigation practice. “Who else on the board knew about these things and when did they know about them?”

Weinstein Co.'s film and television businesses have spiraled in recent weeks after The New York Times and The New Yorker ran scathing reports detailing allegations that Weinstein, a powerful movie producer, had sexually harassed and assaulted women in the industry for decades.

Weinstein has denied sexually assaulting women, and has reportedly checked into a facility known for treating sex addiction.

Weinstein, who founded Weinstein Co. with his brother in 2005 after leaving Miramax, formally resigned from the company Tuesday, after the board ratified its decision to terminate him, according to media reports. But top Hollywood talent and sponsors for shows in the firm's TV business have already distanced themselves from the firm in the wake of the allegations, leading to doubts that the company would be able to continue in its present form.

On Monday, private equity firm Colony Capital said it was in talks to buy Weinstein Co. at what is expected to be a significant discount.

Compounding Weinstein Co.'s troubles, TMZ reported on Oct. 12 that Weinstein's 2015 contract included liquidated damages provisions, which stated that Weinstein would reimburse the company for settlements related to sexual misconduct and then pay an escalating penalty for subsequent settlements or judgment.

Delaware Business Court Insider and other news outlets have not independently verified the report, and a Weinstein Co. representative has since disputed TMZ's interpretation of the contract.

Still, Pileggi said, if that reading of the contract is accurate, it could support allegations that the board was aware of “pervasive and ongoing” wrongdoing and serve as crucial ammunition for a plaintiff looking to make a claim under what is commonly considered to be the most difficult corporate law theory for a Delaware plaintiff to succeed on.

“It at least raises questions under Caremark about whether these were red flags that were ignored,” Pileggi said.

Lawrence Hamermesh, a corporate law professor at Widener University Delaware Law School, questioned TMZ's interpretation, but also acknowledged that such contractual provisions, if they existed, would be deeply troubling—and “almost criminal”—evidence against the Weinstein Co. board.

“It would make it fairly easy to allege that … somebody of authority in the company was aware of the problem,” he said.

But Hamermesh cautioned that Weinstein Co.'s status as a tightly held company meant that it was less prone to derivative litigation because shareholders in private firms are often more familiar with corporate decision-making than investors in large public companies.

“It's not likely to be one of these cases where people are looking at the board, asking, 'Where were you,'” he said.

It was not clear how the Weinstein Co. had structured its corporate governance apparatus, since private firms are not required to disclose that information publicly. To even have standing to bring the suit, however, a plaintiff would have to be an equity investor in the firm, but not a member of its board.

Even then, practical concerns may weigh against filing derivative litigation.

Investors often hold large stakes in private firms like Weinstein Co., and it may be in their financial interest to simply allow the company to be sold for the best possible price.

Also, given Weinstein's stature and reputation in Hollywood, potential plaintiffs would either have to admit that they knew about Weinstein's alleged misconduct or be forced to publicly defend an assertion that they were completely oblivious to it. The former may sink a derivative claim, and the latter could be untenable for a Weinstein Co. investor, likely to be a deep-pocketed player in the Hollywood film industry.

As of Wednesday, no derivative suits had been filed in Delaware.

Tom McParland can be contacted at 215-557-2485 or at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @TMcParlandTLI.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Chancery Court Exercises Discretion in Setting Bond in a Case Involving Share Transfer Restriction

6 minute read

SEC Calls Terraform's Dentons Retainer 'Opaque Slush Fund' in Bankruptcy Court

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

- 2California Court Denies Apple's Motion to Strike Allegations in Gender Bias Class Action

- 3US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

- 4Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

- 5African Law Firm Investigated Over ‘AI-Generated’ Case References

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250