A Year Later: The Impact in Delaware From the US Supreme Court's 'TC Heartland'

Almost one year ago, the U.S. Supreme Court decided the landmark case of TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods Group Brands. The decision upended what had been the status quo on the issue of where venue lies in patent infringement actions.

April 11, 2018 at 10:09 AM

6 minute read

Almost one year ago, the U.S. Supreme Court decided the landmark case of TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods Group Brands, 137 S. Ct. 1514 (May 22, 2017). The decision upended what had been the status quo on the issue of where venue lies in patent infringement actions. The author has written before for the Delaware Business Court Insider about a looming potential for a restriction on where plaintiffs may bring patent infringement lawsuits, first in 2016 when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit acted on a writ of mandamus and issued its opinion on the issue, maintaining a broad interpretation of the applicable venue statutes, and again when the Supreme Court first issued TC Heartland and overruled a 26-year-old precedent of the Federal Circuit. The question had always been whether a Supreme Court ruling would end an era during which, for certain periods, over 40 percent of all patent infringement suits were being brought in the Eastern District of Texas. Now, a year later, there is evidence that this concentration of a single type of litigation in a single district is being redistributed among other historically significant patent infringement litigation venues, including the District of Delaware.

By way of background, in TC Heartland the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that a domestic corporation resides only in its state of incorporation for purposes of patent venue. The long-standing Federal Circuit precedent that TC Heartland reversed, VE Holding v. Johnson Gas Appliance, 917 F.2d 1574 (Fed. Cir. 1990), had interpreted “resides” in the patent venue statute, 28 U.S.C. Section 1400(b), to confer venue in nearly any forum where a defendant was subject to personal jurisdiction, according to the general venue statute, 28 U.S.C. Section 1391, which defined “residence” for corporate defendants. In interpreting the terms residence and resides, VE Holding, according to the Supreme Court, improperly relied on a 1988 amendment to Section 1391(c), which added the clause “for purposes of venue under this chapter” at the beginning of the provision that substantively states: “a corporation may be sued in any judicial district in which it is incorporated or licensed to do business or is doing business, and such judicial district shall be regarded as the residence of such corporation for venue purposes.”

The TC Heartland court thus focused on interpreting the venue statutes and precedent. The court explained that when Congress intends to effect a change of that kind, it ordinarily provides a relatively clear indication of its intent in the text of the amended provision. The current version of Section 1391 does not contain any indication that Congress intended to alter the meaning of Section 1400(b) as interpreted in the seminal Fourco Glass v. Transmirra Products, 353 U.S. 222, 228-29 (1957). Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that Fourco definitively and unambiguously held that the word “reside[nce]” in Section 1400(b) has a particular meaning as applied to domestic corporations: It refers only to the state of incorporation. Congress has not amended Section 1400(b) since Fourco, thus Fourco remains precedential.

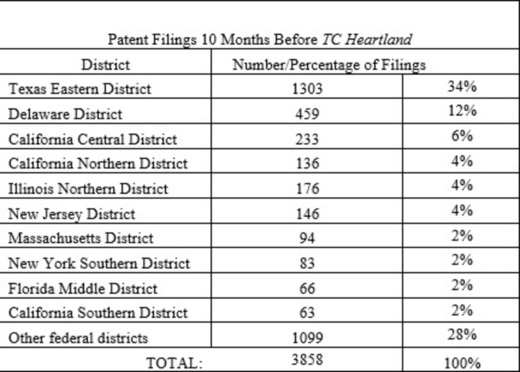

It is undeniable that TC Heartland has affected where patent infringement suits are being litigated. According to data mined from Docket Navigator, in the 10 months before the Supreme Court issued its opinion, plaintiffs filed over 3,800 patent infringement suits. Approximately 34 percent of them were filed in the Eastern District of Texas. By comparison, the nine other most popular federal districts, including the District of Delaware (12 percent), the Central District of California (6 percent), the Northern District of California, the Northern District of Illinois, and the District of New Jersey (each at 4 percent), together accounted for 38 percent of all patent filings. All other federal districts received the remaining 28 percent of the cases.

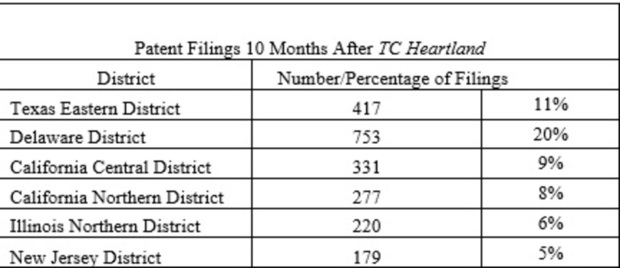

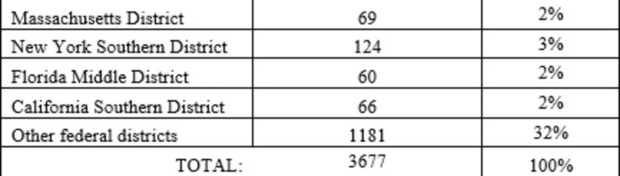

Now, again, a defendant in a patent infringement action may be sued only in the defendant's state of incorporation or where the defendant has “a regular and established place of business” and also committed acts of infringement. In the corresponding 10 months following TC Heartland, the effect on the distribution of patent infringement filings is notable. With a comparable number of patent filings across all federal districts in the 10 months pre- and post-TC Heartland—3,858 before versus 3,677 after—plaintiffs initiated 886 fewer patent cases in the Eastern District of Texas, equating to an approximate 23 percent decline. Delaware on the other hand, has seen the greatest uptick in filings, equating to an approximate 8 percent increase. Further, as compared to the period before TC Heartland, patent infringement suits also increased in each of the Central District of California, the Northern District of California, the Northern District of Illinois and the District of New Jersey.

Taking a closer look at the District of Delaware in particular, where the majority of the “Hatch-Waxman” patent-litigation is filed and litigated, it is interesting to note that the increase in filings is attributable to regular—as opposed “Hatch-Waxman”—patent infringement cases. Generally, the Hatch-Waxman Act permits a branded drug company to sue a generic drug company before any traditional infringing acts have occurred, when the generic drug company only seeks FDA approval to sell a copy of the patented drug. In particular, the rate of such Hatch-Waxman filings in Delaware have remained steady in the wake of TC Heartland, where the non-Hatch-Waxman cases have more than doubled in Delaware as a direct result of the Supreme Court's decision. However, it is not surprising TC Heartland has had less of an impact on Hatch-Waxman litigation, where district courts have struggled to apply Section 1400. For instance, Chief Judge Leonard Stark commented on the problem in a recent opinion, observing “there appears to be a complete mismatch between the backward-looking nature of the patent venue statute and the forward-looking nature of Hatch-Waxman litigation” and thus Section 1400 “creates an almost impenetrable problem in the particular context of Hatch-Waxman patent litigation,” as in Bristol- Myers Squibb v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals (D. Del. Sept. 11, 2017). As a result, while TC Heartland re-established the location where the majority of patent infringement suits are filed, issues remain in the context of Hatch-Waxman litigation.

James S. Green Jr. is a partner at Landis Rath & Cobb, where his practice is focused on complex business litigation in Delaware state and federal courts, including patent litigation in the District of Delaware. He can be contacted at 302-467-4426 or at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

IPO to Insolvency: Big Law Isn't Done Making Money on EV SPACs

Agreeing to Wider Customer Notice, FTX to Settle Claims Out of Delaware Court

4 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250