Mastering the E-Beast

Companies should implement thoughtful records retention programs to reduce the costs of e-discovery.

March 27, 2011 at 08:00 PM

9 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Law.com

As in-house counsel know, litigation sometimes is hard to avoid, discovery is probably the most expensive part of litigation and the proliferation of electronically stored information ( ESI) has made discovery more complicated and expensive than ever. In 1996, back when people still used paper, my article “Taming the Paper Tiger,” which appeared in Litigation Management & Economics, decried the complexity and expense of managing all of the paper records potentially discoverable in complex litigation. Little did we know how good we had it then–or how much worse it could get. Now, instead of taming the paper tiger we are faced with mastering the e-beast.

So how do we master this dangerous beast? There is no magic lasso, but we are seeing progress on several fronts. The 2006 Federal Rules amendments provide some protection against having to produce ESI that is “not reasonably accessible due to undue burden or cost.” The Sedona Conference, a widely renowned nonprofit think tank that provides guidance on e-discovery and other issues, has several working groups that have developed constructive suggestions for improving discovery, and those suggestions often gain traction in the courts. For example, the 2008 Sedona “Cooperation Proclamation,” encouraging parties to cooperate to agree to reasonable limitations with regard to discovery, has now been endorsed by at least 110 state and federal judges. In October of 2010 we saw release of the Sedona Conference Commentary on Proportionality in Electronic Discovery, recommending that courts give real meaning to the provisions Fed. R. Civ. P. 1, providing that the rules “should be construed and administered to secure the just, speedy and inexpensive determination of every action…” (emphasis supplied). Most states have analogous provisions in their state rules of civil procedure.

Yet, to date, these efforts have only slightly subdued the e-beast. There is still a long way to go before many courts abandon the presumption that everything is discoverable regardless of how difficult to find, how likely to be cumulative, how unlikely to be material to truly contested issues or how high the cost of the chase in comparison to the amounts at issue in the case. At the same time, the proliferation of electronic information is continuing to feed the beast, and making it grow larger.

Here are several “great” ideas some companies are adopting: (i) let's take all of our telephone voicemails and automatically transcribe them into emails–or better attach the voice files to emails to be retained (and discoverable at enormous cost) indefinitely; (ii) let's embrace instant messaging and start journaling all of the instant messages and texts to retain those forever as well; (iii) let's save our disaster recovery backups for months or years instead of only days or weeks; (iv) whenever any employee leaves the company, let's image the hard drive of their computer so that we retain that forever as well; and (v) let's get bigger hard drives on our next purchase of PCs so that employees will have plenty of storage space to save emails in .pst files that never get deleted. Or better still, let's buy an archiving system or service that we can set up to save all emails forever. After all, you never know when you are going to need to find 5,000 or so old offers for Viagra!

As the above examples illustrate, the first line of corporate defense is to take into account e-discovery risks and exercise common sense with regard to record retention before litigation ever hits. It's not just the careless or sarcastic comments that are too often found in employee e-mail or other electronic records–and then used to make the whole company look bad. Even if all of the information is innocuous, you can spend a fortune collecting, filtering and reviewing massive volumes of data.

Systems should be set up to keep records available and readily accessible only as long as needed for legitimate business purposes or legal compliance. After that, procedures and mechanisms are needed to ensure that the obsolete records are deleted–including all electronic copies of them. Of course, you also need the ability to “turn off” any automated deletion programs in the event of pending or reasonably anticipated litigation or an investigation, in order to avoid any potential for spoliation of evidence.

Sound records management can help reduce the problem, but more help clearly is needed. The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania is now undertaking an interesting experiment with the use of E-Discovery Special Masters. They have developed a pool of lawyers, and at least one former judge, to serve as special masters–all successful candidates had to demonstrate training and experience in complex litigation, e-discovery and mediation, and then go through a training course set up and supervised by the court. More than 40 approved candidates–including a number of experienced practitioners from outside of Pennsylvania–will soon be available for appointment in cases where parties request, or where the court otherwise deems appropriate.

Can knowledgeable special masters help litigation parties and courts master the ferocious e-beast? Stay tuned!

As in-house counsel know, litigation sometimes is hard to avoid, discovery is probably the most expensive part of litigation and the proliferation of electronically stored information ( ESI) has made discovery more complicated and expensive than ever. In 1996, back when people still used paper, my article “Taming the Paper Tiger,” which appeared in Litigation Management & Economics, decried the complexity and expense of managing all of the paper records potentially discoverable in complex litigation. Little did we know how good we had it then–or how much worse it could get. Now, instead of taming the paper tiger we are faced with mastering the e-beast.

So how do we master this dangerous beast? There is no magic lasso, but we are seeing progress on several fronts. The 2006 Federal Rules amendments provide some protection against having to produce ESI that is “not reasonably accessible due to undue burden or cost.” The Sedona Conference, a widely renowned nonprofit think tank that provides guidance on e-discovery and other issues, has several working groups that have developed constructive suggestions for improving discovery, and those suggestions often gain traction in the courts. For example, the 2008 Sedona “Cooperation Proclamation,” encouraging parties to cooperate to agree to reasonable limitations with regard to discovery, has now been endorsed by at least 110 state and federal judges. In October of 2010 we saw release of the Sedona Conference Commentary on Proportionality in Electronic Discovery, recommending that courts give real meaning to the provisions

Yet, to date, these efforts have only slightly subdued the e-beast. There is still a long way to go before many courts abandon the presumption that everything is discoverable regardless of how difficult to find, how likely to be cumulative, how unlikely to be material to truly contested issues or how high the cost of the chase in comparison to the amounts at issue in the case. At the same time, the proliferation of electronic information is continuing to feed the beast, and making it grow larger.

Here are several “great” ideas some companies are adopting: (i) let's take all of our telephone voicemails and automatically transcribe them into emails–or better attach the voice files to emails to be retained (and discoverable at enormous cost) indefinitely; (ii) let's embrace instant messaging and start journaling all of the instant messages and texts to retain those forever as well; (iii) let's save our disaster recovery backups for months or years instead of only days or weeks; (iv) whenever any employee leaves the company, let's image the hard drive of their computer so that we retain that forever as well; and (v) let's get bigger hard drives on our next purchase of PCs so that employees will have plenty of storage space to save emails in .pst files that never get deleted. Or better still, let's buy an archiving system or service that we can set up to save all emails forever. After all, you never know when you are going to need to find 5,000 or so old offers for Viagra!

As the above examples illustrate, the first line of corporate defense is to take into account e-discovery risks and exercise common sense with regard to record retention before litigation ever hits. It's not just the careless or sarcastic comments that are too often found in employee e-mail or other electronic records–and then used to make the whole company look bad. Even if all of the information is innocuous, you can spend a fortune collecting, filtering and reviewing massive volumes of data.

Systems should be set up to keep records available and readily accessible only as long as needed for legitimate business purposes or legal compliance. After that, procedures and mechanisms are needed to ensure that the obsolete records are deleted–including all electronic copies of them. Of course, you also need the ability to “turn off” any automated deletion programs in the event of pending or reasonably anticipated litigation or an investigation, in order to avoid any potential for spoliation of evidence.

Sound records management can help reduce the problem, but more help clearly is needed. The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania is now undertaking an interesting experiment with the use of E-Discovery Special Masters. They have developed a pool of lawyers, and at least one former judge, to serve as special masters–all successful candidates had to demonstrate training and experience in complex litigation, e-discovery and mediation, and then go through a training course set up and supervised by the court. More than 40 approved candidates–including a number of experienced practitioners from outside of Pennsylvania–will soon be available for appointment in cases where parties request, or where the court otherwise deems appropriate.

Can knowledgeable special masters help litigation parties and courts master the ferocious e-beast? Stay tuned!

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump's SEC Likely to Halt 'Off-Channel' Texting Probe That's Led to Billions in Fines

Companies' Dirty Little Secret: Those Privacy Opt-Out Requests Usually Aren't Honored

Ballooning Workloads, Dearth of Advancement Opportunities Prime In-House Attorneys to Pull Exit Hatch

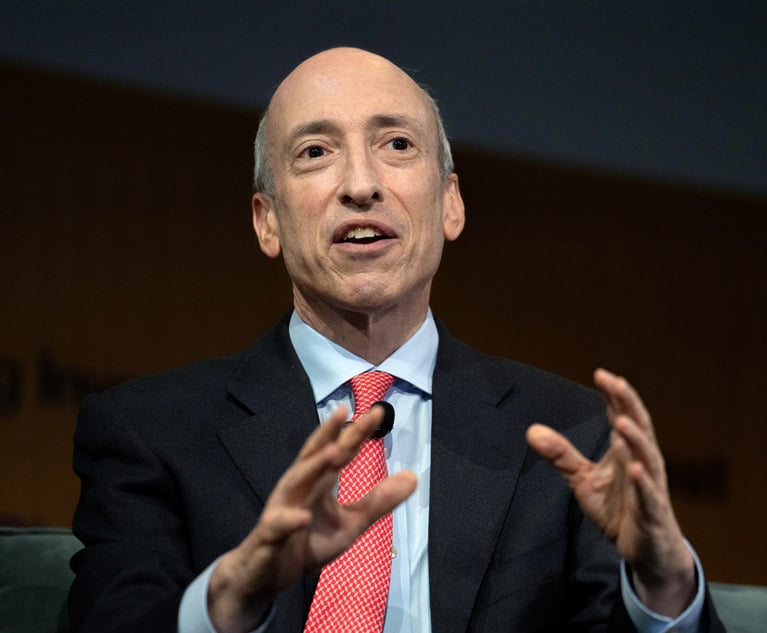

Am Law 100 Partners on Trump’s Short List to Replace Gensler as SEC Chair

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Commentary: James Madison, Meet Matt Gaetz

- 2The Narcissist’s Dilemma: Balancing Power and Inadequacy in Family Law

- 3Leopard Solutions Launches AI Navigator, a Gen AI Search, Data Extraction Tool

- 4Trump's SEC Likely to Halt 'Off-Channel' Texting Probe That's Led to Billions in Fines

- 5Special Section: Products Liability, Mass Torts & Class Action/Personal Injury

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250