US Briefing: Opportunities and threats

Ryan Rettmann left Thacher Proffitt & Wood in the nick of time. Last March, not long before the subprime crash paralysed the debt markets, the first-year structured finance associate moved to Chicago's Kirkland & Ellis. At Thacher Proffitt, he had been working on securities backed by home mortgages, a niche that was dead in the water by the end of summer. At Kirkland, he took a job working on auto-loan securitisations, a considerably healthier asset class. Rettmann was not prescient, just in love. He and his new wife had decided to leave New York and settle in Chicago, where he lined up the Kirkland interview after one phone call.

March 19, 2008 at 11:48 PM

8 minute read

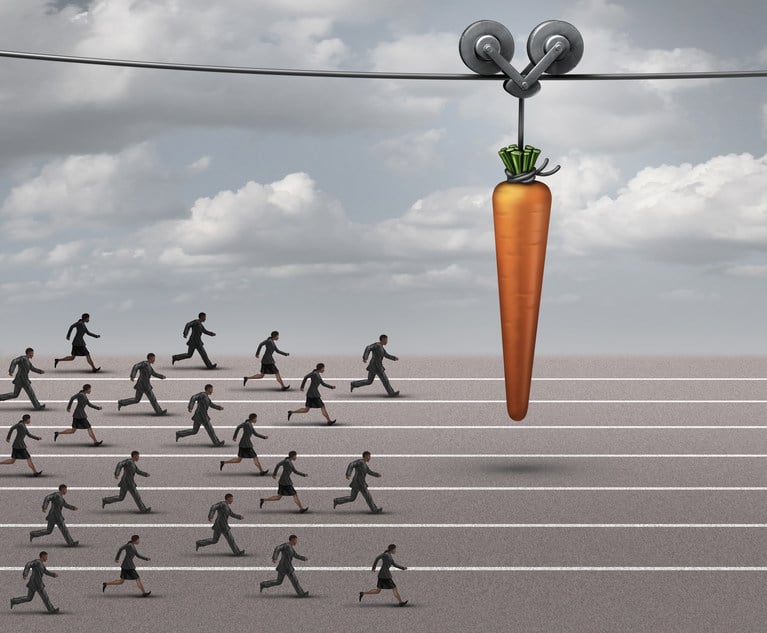

Does a recession mean lay-offs or is it a time to snag laterals? Your view probably depends on your place in the firm hierarchy, says Ben Hallman Ryan Rettmann left Thacher Proffitt & Wood in the nick of time. Last March, not long before the subprime crash paralysed the debt markets, the first-year structured finance associate moved to Chicago's Kirkland & Ellis. At Thacher Proffitt, he had been working on securities backed by home mortgages, a niche that was dead in the water by the end of summer. At Kirkland, he took a job working on auto-loan securitisations, a considerably healthier asset class.

Rettmann was not prescient, just in love. He and his new wife had decided to leave New York and settle in Chicago, where he lined up the Kirkland interview after one phone call.

"I got lucky," he says. "At the time, structured finance was so hot that it was easy to get a job."

How quickly times have changed. With financial institutions battered by bad bets on subprime mortgages and the stock market staggering like a drunken sailor, law firms are bracing for disaster. In January a report from consulting firm Hildebrandt International and Citigroup Private Bank said some firms had already experienced a "significant" drop in productivity in the third quarter of 2007. This year, the study concluded ominously, was shaping up to be the worst since 2001.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the recession: it seems that anxiety, like income, is not evenly apportioned within the legal profession. Since January, The American Lawyer has interviewed dozens of partners, associates, consultants and legal recruiters in threatened practice areas – structured finance, real estate, M&A and private equity. Not one of these people denied there are storm clouds on the horizon, but there was an interesting pattern in how much of a soaking they expect.

Among associates, anxiety is high, even though laid-off young lawyers are, so far, finding new jobs. Nevertheless, many associates echoed the sentiments of Kirkland's Rettmann, who says he scans The Wall Street Journal every day for news about market turmoil.

"I am nervous," says one corporate associate at a New York law firm that is already anticipating a downturn. This associate says he is reviewing contracts in anticipation of mortgage-backed securities-related litigation but does not know how long that work will last. "And my firm doesn't tell us anything," he says.

Partners, meanwhile, are blase – even focused on the lateral opportunities of a roiled market. And law firm managers? Dan DiPietro at Citigroup Private Bank says he is hearing "tremendous angst about 2008″, with almost daily questions about "how difficult the year will be".

But most of the nine Am Law 100 firm leaders interviewed for this story insist that their firms are superbly positioned; they are worried about how the other guys will handle whatever the market throws at them. It is a strange phenomenon: the level of fear that lawyers expressed was in inverse proportion to their level of seniority.

Brian Brooks falls squarely in the 'not worried' category. Brooks is the head of O'Melveny & Myers' Washington DC office and a member of the firm's executive committee. In recent weeks, rumours that O'Melveny was culling associates through unusually harsh performance reviews bloomed on the internet. Brooks says the stories are simply not true. "Unfortunately, the routine annual bonus process coincided with rumours that the economy is about to crater," he says.

The number of associates who received low performance evaluations, he adds, was about 5% of the total N the same as in 2007. Firm-wide, Brooks says, O'Melveny is in good shape. The firm does not do quite as well in up-cycles as its peer group, he notes, but has strong restructuring and litigation practices that thrive when the economy weakens. "Times like this give us an opportunity to shine," he says.

Ralph Baxter is also confident N at least for his own firm, Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe. "We are not lawyers to the entire economy," Baxter says. "We are lawyers to our clients. The need for our services does not go away simply because the economy is less robust." (Ten percent of Orrick's revenue is from structured finance work, but Baxter says that includes all sorts of securitisations.) "The most important thing to say about 2008," says Baxter, "is that we do not know what is going to happen."

Even the severe downturn in deal work is not daunting to some prominent practice leaders. "The private equity guys are very creative," says Alan Klein, a Simpson Thacher & Bartlett partner. "They have a lot of equity that they have to spend." Some of those dollars will likely go for 'pipes' transactions, in which investors buy a piece of a company instead of the whole thing, he says. He also predicts more deals in Asia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe and a continued healthy clip for smaller buy-outs.

In the meantime, Simpson Thacher will be busy doing ancillary work related to the $156bn (£77bn) worth of deals the firm helped broker last year. Still, Klein says, there is no question that people are worried. Dozens of signed deals have come apart in the last year, a collapse that Klein, a 30-year veteran, describes as "unfathomable".

But in a now-familiar refrain, private equity partners are saying that everything depends on positioning. At Kirkland, for instance, Frederick Tanne is blunt about the year to come. "In terms of the market, it is going to be a more difficult year for private equity," he says. "Anyone who says different is smoking something."

Nevertheless, Tanne says that Kirkland, whose strength is in the smaller buy-outs that are likely to account for most of the dealmaking in the next year, will be fine. The firm handled 85 private equity transactions in 2007, at an average of $1.2bn (£592m) each. By way of comparison, Simpson Thacher handled 29 buy-outs at an average of $5.4bn (£2.7bn) each.

Experienced partners like Klein and Tanne can take the long view. Associates are quicker to panic, especially when they believe they are being kept in the dark by their firms, but early indications suggest that those who have already been hit hardest by the downturn – the 100 or so structured finance associates who were fired or bought-out in recent months – are finding other jobs.

Thacher Proffitt and McKee Nelson, where 52 associates accepted buy-out offers, say that all but one got new jobs, most right away. Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft, which laid off 35 associates in January, says it expects most to find new positions at other firms, though it is too early to say for sure. Dozens more young lawyers, such as Timothy Hauck, a former first-year Thacher Proffitt associate, left their firms last autumn and winter, before the buy-outs were offered. Hauck landed on his feet and is now a corporate associate at Arnold & Porter.

The lesson here: if there is pain in a downturn, there is also opportunity. Good performers, regardless of practice area, should be able to find other work. "It is an opportunity for firms to pick up good people if they are willing to take the risk that they won't be busy for a while," says Bradford Hildebrandt.

That goes for partners, too. Peter Zeughauser of the Zeughauser Group says that firms whose profits per partner were in the bottom third of the Am Law 200 are likely to lose talented young lawyers – and have only themselves to blame. As the economy slows, dissatisfied partners are expected to change jobs in record numbers. This has legal recruiters licking their lips. "It could be the busiest year ever," says one.

A busy lateral marketplace is one of the few sure bets in the coming months. For everyone else, the watchword is uncertainty. Predicting future business cycles is a puzzle that economists, much less lawyers, are unable to solve. Just ask McKee Nelson, which last fall offered buy-outs to 23 under-worked associates. "I have been beating myself up over this for months now," says Reed Auerbach, head of the firm's New York office. "But then I realise there are smarter people that didn't see this coming."

A version of this article appears in the March edition of The American Lawyer, Legal Week's US sister title.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms 'Struggling' With Partner Pay Segmentation, as Top Rainmakers Bring In More Revenue

5 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250