Fitting the bill

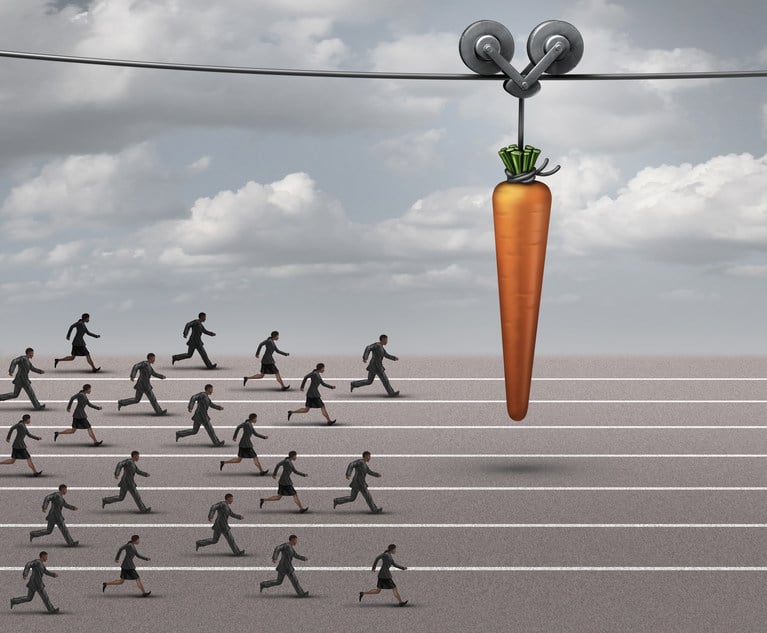

Compelled to try to control legal costs, general counsel across the land are hypnotically drawn to billing-rate discounts. 'Eight percent off your standard rates' mesmerises those who have to account for spending on outside counsel. "Look what we've saved!" they proclaim. Well, maybe.I am suspicious of discounts on legal fees as a cost-control tool. Ultimately they do not alter the dysfunctionality of hourly billing. Law firms still enjoy a cost-plus arrangement, inducements to pad out law firm bills are everywhere and in-house lawyers must still scrutinise long bills. Several other aspects of fee discounts are problematic, too.

May 07, 2008 at 08:16 PM

8 minute read

Do billing-rate discounts really control costs? Rees Morrison finds there is less than meets the eye when it comes to discounting legal fees as a cost-control tool

Compelled to try to control legal costs, general counsel across the land are hypnotically drawn to billing-rate discounts. 'Eight percent off your standard rates' mesmerises those who have to account for spending on outside counsel. "Look what we've saved!" they proclaim. Well, maybe.

I am suspicious of discounts on legal fees as a cost-control tool. Ultimately they do not alter the dysfunctionality of hourly billing. Law firms still enjoy a cost-plus arrangement, inducements to pad out law firm bills are everywhere and in-house lawyers must still scrutinise long bills. Several other aspects of fee discounts are problematic, too.

From what baseline?

Let's start with this question: when a law firm agrees to discount its 'standard hourly rates', how does the in-house lawyer know the firm's rack rates? Law firms do not routinely publish their standard rate cards. In fact, if firms are well managed, they tailor rates according to the strength of the practice, the demand for it, the kind of work on offer from the particular company, personal relationships and more.

Shaving something off a mythical rate might sound good, but what the company really wants is to be billed at rates that are, by some definition, advantageous. The company might not have the clout, cash or cachet to be entitled to the most favourable rates of the firm, whatever those are, but when it requests discounts, it wants to be treated better than other, non-discounted clients.

How to confirm that status is one major problem with discounts. In a world where all too many clients get 'discounted' rates, there may be no relative gain.

Prove it

Another problem is how to prove what the company has actually saved. If every-thing remained the same – including the lawyers working on the matters, the hours they all work and the kind of work required – then discounts would easily compute into savings. Things do not stay the same.

If you can calculate the effective billing rate of a law firm before it imposes a discount, you can test whether that effective rate has, in fact, declined by the amount of the discount several months later (a firm's effective billing rate is the total fees billed divided by the total hours billed). That comparison is clouded by the arrival of new timekeepers and the departure of former timekeepers – not to mention the changing distribution of hours among the consistent billers.

A worm in the apple

What has always been troubling about billing-rate discounts is whether firms make up for the discount by billing a few more hours. It is unknown and probably unknowable whether an additional hour or two, here or there, tucked into a long invoice, wipes out the putative discount.

I suspect that associates do not know about the discounts applicable to matters they work on, but the billing partner certainly does. Nor do associates know or care about how much of each dollar billed the firm collects – that is, the realisation rate. But if realisation rates count for much in compensation decisions, the partners will know; and the urge to sprinkle in a few extra hours may overcome some of them. The in-house lawyer tasked to review the bill may be stymied trying to find those scattered incremental hours.

Think of your primary law firm. If its average standard rate is £300 per hour with a gross margin of 35%, the firm makes a profit of £195 each hour. That profit is reduced by nearly 30% if it grants you a 10% discount (£30 per hour). To maintain its total profits at the same level, the firm needs to bill you for 40% more hours. But if it bills you for just a few more hours here and there, that also reduces its loss and effectively wipes out your savings.

Swamped by pay hikes

Billing for more hours is one way to keep up profits; raising rates is another. As law firms boost rates, discounts fail to keep pace. Managing partners may well anticipate requests for discounts by building in a little bit extra so they can amiably agree to a phantom concession. You shouldn't pat yourself on the back for wringing out a 7% discount if the hourly rates have jumped by 12%.

What I am suggesting is that, for some long-running matters, it would be cheaper to hire lawyers who bill at their full rates but guarantee not to raise those rates for the next year or two.

Define 'usual'

Another challenge for counsel seeking discounts is that there are no shared benchmarks on what leaves money on the table versus what is over-reaching. Based on my consulting experience with many corporate law departments, it is routine to obtain a 5% discount merely by asking.

To push the discount level up to 7%, the company needs to retain the firm for a number of years and put it to work on fairly significant matters. At 10% discounts, the law firm's billing committee becomes engaged. The firm probably wants close to seven figures in fees and some expectation of ongoing volume.

Some law departments wrangle 15% discounts, but those seem to be for major acquisitions or huge lawsuits. If you dangle £1m or more in fees in one fell swoop, a firm might oblige with a 15% discount. After all, the firm benefits by locking in a large amount of work over a period of time without any marketing costs.

When nosebleed discounts of 20% or more come about, there is some mix of whopping fee volumes, clients in dire financial straits, law firms seeking to break into a practice area, and/or persuasively insistent general counsel.

Profit margins at many large law firms are upwards of 25%. So the ability to shave that margin by some portion – if indeed a discount translates into a reduction – should not surprise anyone. In short, discounts sound good, but do you know when you have locked?

One size fits none

When turning to discounts to cut legal fees, most companies attempt to impose a blanket discount on all their primary law firms. It seems equitable, but an across-the-board discount may be a blunderbuss response. It actually penalises law firms that were charging competitive rates. A firm with an effective billing rate of £450 an hour may find it much easier to swallow that 10% discount than a firm running leanly at £350 an hour.

Moreover, if the two firms billed the same number of hours with the same distribution of those hours among partners, associates and paralegals, a gaudy discount from a very expensive firm would prove more costly than no discount from a relatively inexpensive firm. No law department should insist on discounts that drive away efficient firms while deluding itself about savings from expensive firms that shave a little off their stratospheric rates.

It may make more sense to request that firms lower their billing rates by class level. For example, perhaps first-year associates should have their billing rate discounted 60%; second-year associates, who have begun to deliver a little more value, might be discounted by 30%; and so forth. The assumption – and it is a good one – is that the less experienced the lawyer, the more likely that lawyer's rates are too high for the value delivered.

Fine-tuning such as this would require an electronic billing system that kept an eye on whether rates billed conformed to discounts granted. Such software would instantly point out when firms were not honouring the discounts they had proffered. Without it, somebody still has to eyeball the bill to make sure that each timekeeper is billed at the agreed-upon rate.

Best of the worst

For their part, law firms emphasise the nominal value of the discounts they grant in various ways. The best way is to have each invoice show the total amount of the bill and then, on a separate line, the discount applied. Everyone can read that clearly.

But displaying the reduction is the simple part. Other disabilities – 'standard' rates, provability of savings, additional hours billed, rate increases, appropriate levels and even-handed applicability – handicap the usefulness of fee discounts. Better than no discounts, to be sure. Well, maybe.

Perhaps discounts are like democracy: flawed, but better than any other fee management method. Alternative billing arrangements, such as fixed fees or value determinations for completed matters, raise formidable complexities. Discounts to billing rates are, by contrast, clean and well-understood, with manifest savings.

And that is why they will continue to be favoured. Just as hourly billing is the whipping boy of critics yet somehow survives, discounted billing rates are rife with problems, but no other technique for reducing legal fees works better.

The author is a consultant at Rees Morrison Associates.NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

KPMG's Bid To Practice Law in US On Hold As Arizona Court Exercises Caution

Law Firms 'Struggling' With Partner Pay Segmentation, as Top Rainmakers Bring In More Revenue

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Who Is Nicholas J. Ganjei? His Rise to Top Lawyer

- 2Delaware Supreme Court Names Civil Litigator to Serve as New Chief Disciplinary Counsel

- 3Inside Track: Why Relentless Self-Promoters Need Not Apply for GC Posts

- 4Fresh lawsuit hits Oregon city at the heart of Supreme Court ruling on homeless encampments

- 5Ex-Kline & Specter Associate Drops Lawsuit Against the Firm

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250