Pay attention

Salary surveys have become something of a fixture of the in-house world but, as popular as their production is among recruitment professionals, there has been little debate about how useful - or how widely used - they are by their intended audience.Of course, no one disputes the demand for research that can provide lawyers working outside the highly structured world of private practice with a yardstick by which to judge their own compensation. But with salaries and bonuses widely varying as the type, sector and geography of the companies looking to recruit, just how useful are current surveys on the market? Are such surveys a true reflection of the earnings of lawyers working in-house? And what is the general quality of the research behind such initiatives?

November 12, 2008 at 11:02 PM

7 minute read

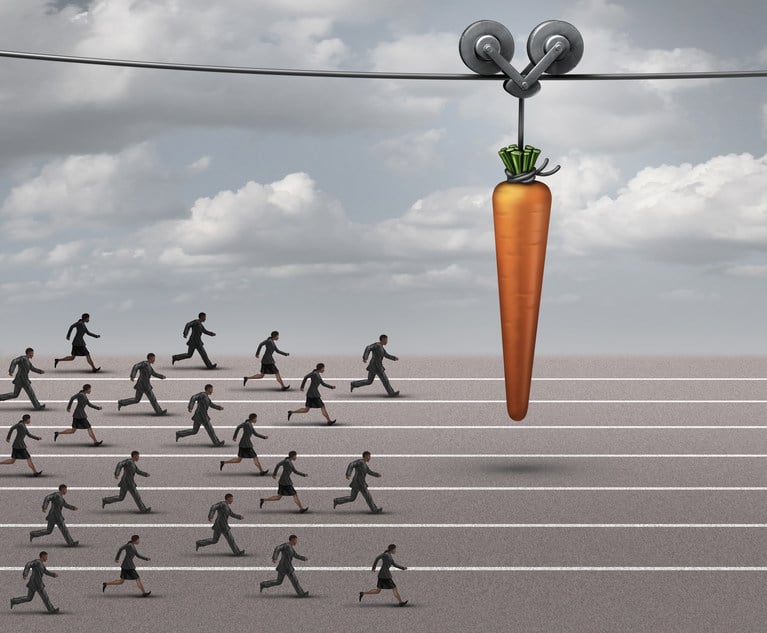

Salary surveys have become a fixture of the in-house recruitment market. But, finds Leigh Jackson, benchmarking general counsel pay is more art than science

Salary surveys have become a fixture of the in-house recruitment market. But, finds Leigh Jackson, benchmarking general counsel pay is more art than science

Salary surveys have become something of a fixture of the in-house world but, as popular as their production is among recruitment professionals, there has been little debate about how useful – or how widely used – they are by their intended audience.

Of course, no one disputes the demand for research that can provide lawyers working outside the highly structured world of private practice with a yardstick by which to judge their own compensation. But with salaries and bonuses widely varying as the type, sector and geography of the companies looking to recruit, just how useful are current surveys on the market? Are such surveys a true reflection of the earnings of lawyers working in-house? And what is the general quality of the research behind such initiatives?

The difficulty of trying to compile accurate figures on the wages of in-house lawyers is illustrated by looking at the range of different studies in the market place.

The In-house Lawyers Pay Report 2008, compiled by Thomson Reuters company IDS, is one example of the challenge of providing meaningful cross-industry benchmarks. The IDS research gives a detailed breakdown of pay across various levels of employees and different sectors, and puts together a range of medians and averages.

The survey found that the average pay for a UK head of legal stood at £131,502. However, taking a look at the figures more closely, the survey found that the lowest-earning respondent among general counsel, a legal head working in the manufacturing sector, earned less than £30,000, while the highest-earning general counsel, working at a finance company, received a wage of £378,000.

While the wide difference is partly explained by differing industries, even within single groupings wide disparities often occur.

And the differences in benchmarks become more pronounced if the findings from two different surveys are compared. According to Hughes Castell's latest salary summary, the typical basic pay for a general counsel working in a media company is between £100,000 and £180,000. The comparative figure in Taylor Root's latest salary guide is between £132,000 and £184,000.

Although both surveys explain that the numbers are to be used as a guideline and not a scientific measure, by consensus, it is challenging for such research to establish genuinely comparable benchmarks.

If it is agreed that it is hard to create accurate measures of the salaries of in-housers, are they still a useful tool? The general consensus among recruitment professionals is yes.

Tracy Brown, a recruiter in the legal division of Barclay Simpson, says that job seekers benefit from the research.

"Candidates use them to pitch themselves at the right level in the market and also to gauge what they could get by moving into a different area of law or sector," she says. "Candidates who have been out of the market for considerable amounts of time and are a little out of touch with salary levels also find them useful."

Brown says that the research can be used as a guide for recruiters themselves, providing general information clients may request.

"Spending time to produce a detailed report twice a year is much more credible than just giving limited information when asked for it," she says. "It also means that we are consistent with the information that we are providing and, although time-consuming, initially it saves us a lot of time in the long run."

Brown's view is shared by Laurence Simons managing director Naveen Tuli (pictured). Laurence Simons produces a global salary survey which, according to Tuli, provides a detailed and valuable guide for the consultants themselves.

Brown's view is shared by Laurence Simons managing director Naveen Tuli (pictured). Laurence Simons produces a global salary survey which, according to Tuli, provides a detailed and valuable guide for the consultants themselves.

Tuli says: "The survey is something that every consultant keeps on his or her desk. For clients conducting pan-European searches, for example, it helps them keep within budget."

While the feeling among recruiters is that the study is a valuable tool for both consultants and candidates, many claim that the difficulty in producing an in-house survey means that the studies are most effective as a point of reference rather than definitive guide.

Tuli comments: "Although the survey is based on hard data from our database and candidate offers, it can only be viewed as a useful guide rather than a scientific study."

With a number of variables constantly in play, it can be tricky to make an accurate estimate of what a candidate would be likely to receive as a salary. The size, geography and sector of company all make producing data difficult.

Scott Gibson, director for Hughes-Castell, says that, unlike private practice surveys, in-house data is much more difficult to band as there is a less defined career track, and industries and company structures vary so widely.

And although law firms have widely recognised levels such as trainee, assistant, associate and partner, job titles within companies are far less standardised.

To account for this, Gibson argues that such research has to be specific to particular locations and industries to be of use. "In private practice if you know the level of post-qualification experience, type of firm and location of a candidate, you can usually accurately assess salary to within a few thousand pounds.

"The same is generally not the case for in-house legal departments unless they are highly localised and of a type, for example, investment banking salaries, which tend to be capital market related and based in central London."

Gibson says that lower job mobility in-house makes salaries even harder to benchmark.

He adds: "The relative infrequency of legal recruitment means there can be a tendency for HR departments or even some department heads to become out of touch with prevailing market rates in legal until they are required to hire – a situation which can lead to wide bandings.

But while recruiters still support the salary survey, a straw poll of in-house lawyers finds they are perhaps less viewed than some imagine.

Craig Duncan, Europe, Middle East and Africa general counsel at Reliance Globalcom company Vanco, believes salary research is of most value when it places in-house salaries in the context of the pay structure of companies.

Duncan says: "The surveys are not as effective as looking at the earning structure within an organisation itself. Lawyers are like any professionals and will be subject to a pay scale within their company."

Another issue was that of independence. One recruiter, who asked not to be named, says that respondents may not always give the most accurate responses.

The recruiter comments: "The results that are produced could be questionable – they allow lawyers in-house to benchmark their own salary and they have a vested interest. Some companies use the evidence to show their high pay bracket."

"There is probably scepticism on the part of all parties, a third party creating the results would have no vested interest but both the client and the candidate could be interested in creating wage inflation."

Looking to the future, it seems that recruiters are more focused on improving the quality of their salary research rather than moving away from the concept entirely. In addition, some of the more ambitious consultants are increasingly interested in extending the concept to bespoke, company-specific research as a means of producing more meaningful data.

Karen Horton, a recruiter with LPA Legal, says: "Sometimes companies will specifically request that we do research for them and they will send through the details of their employees. We will then use the information to benchmark the salaries against the market to see whether they are paying the right amount."

Laurence Simons, which also produces an individualised service for companies, also sees potential in specialised research. Tuli comments: "The bespoke benchmarking for multinationals is tailored and a lot more accurate."

Sign up to receive In-house News Briefing, Legal Week's new digital newsletter

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

KPMG's Bid To Practice Law in US On Hold As Arizona Court Exercises Caution

Law Firms 'Struggling' With Partner Pay Segmentation, as Top Rainmakers Bring In More Revenue

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1AIAs: A Look At the Future of AI-Related Contracts

- 2Litigators of the Week: A $630M Antitrust Settlement for Automotive Software Vendors—$140M More Than Alleged Overcharges

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Linklaters Hires Four Partners From Patterson Belknap

- 5Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise, Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250