With pregnancy discrimination cases rising, flexibility is key to retaining talented women

I was surprised to read earlier this year about the employment tribunal case of trainee Katie Tantum suing her former employer, Travers Smith, for unfair dismissal and pregnancy discrimination. She claims she was not kept on after her training contract because she became pregnant in her final seat. I was surprised not by her allegations, but by the fact that: (1) she actually brought a claim; and (2) it got all the way to a hearing. Cases of pregnancy and maternity discrimination rarely reach the public domain. In fact, according to research carried out by the Equal Opportunities Commission in 2005, only 3% of women suffering this type of discrimination complained to an employment tribunal. Most of these cases will settle pre-hearing.

April 11, 2013 at 07:03 PM

5 minute read

Travers unfair dismissal case marks rare example of discrimination claim reaching hearing, says Harriet Bowtell

I was surprised to read earlier this year about the employment tribunal case of trainee Katie Tantum suing her former employer, Travers Smith, for unfair dismissal and pregnancy discrimination. She claims she was not kept on after her training contract because she became pregnant in her final seat. I was surprised not by her allegations, but by the fact that: (1) she actually brought a claim; and (2) it got all the way to a hearing.

Cases of pregnancy and maternity discrimination rarely reach the public domain. In fact, according to research carried out by the Equal Opportunities Commission in 2005, only 3% of women suffering this type of discrimination complained to an employment tribunal. Most of these cases will settle pre-hearing.

The very short three-month time limit for lodging a discrimination claim is no doubt partly to blame, often falling in the later stages of pregnancy or soon after the birth. Women's concern for their and their baby's health, stress and anxiety and damage to career prospects are also contributing factors.

The very short three-month time limit for lodging a discrimination claim is no doubt partly to blame, often falling in the later stages of pregnancy or soon after the birth. Women's concern for their and their baby's health, stress and anxiety and damage to career prospects are also contributing factors.

But the number of cases of pregnancy and maternity discrimination we see seems to be increasing. This is in part due to the economic downturn and the increase in women on maternity leave being made redundant. They are often viewed as an 'easy target', not being in the workplace, and, at such a vulnerable time in their careers, are less likely to complain about being dismissed unfairly.

Let's look at a typical example; we'll call her Emily. Having had no contact from her employer during her maternity leave, Emily got in touch with her employer to discuss her return to work. Her new boss invited her in for a 'get to know you' chat only to then inform her, in the meeting, that 'regrettably' he was making her redundant and there was nothing else for her.

In this situation, Emily's employer had an obligation to offer her a suitable alternative role, if one existed, without her having to apply. Many employers appear unaware of this, or fail to inform the employee of any such role immediately after their role becomes redundant.

In another scenario, Erica returned from maternity leave only to be made redundant a few weeks later, not having been given back any of her pre-leave work. She was also made to feel unwelcome on her return and not integrated back into the workforce.

Her employer used the subjective criterion 'commitment to the job' when selecting her for redundancy, which could be translated as a willingness to stay late. Many women with young children are unable to do this on a regular basis and use of such a criterion to select a woman for redundancy would be indirect sex discrimination.

On the flip side, Jacqueline was prepared to carry out the demanding hours that her pre-maternity leave role involved. However, her employer made an assumption about what Jacqueline, as a new mother, was not prepared to do. She also scored low on this criterion and was also discriminated against, indirectly.

Tantum's allegation that she was not kept on at Travers Smith post-qualification because she became pregnant is unusual. We more commonly see women later on in their career who have perhaps been promised partnership or other promotions that mysteriously disappear once their pregnancy is announced, or sometimes just before or on return from maternity leave.

Sometimes obstacles are suddenly put in the way of promotion that did not previously exist. It can be hard to prove that such treatment is due to pregnancy or maternity leave.

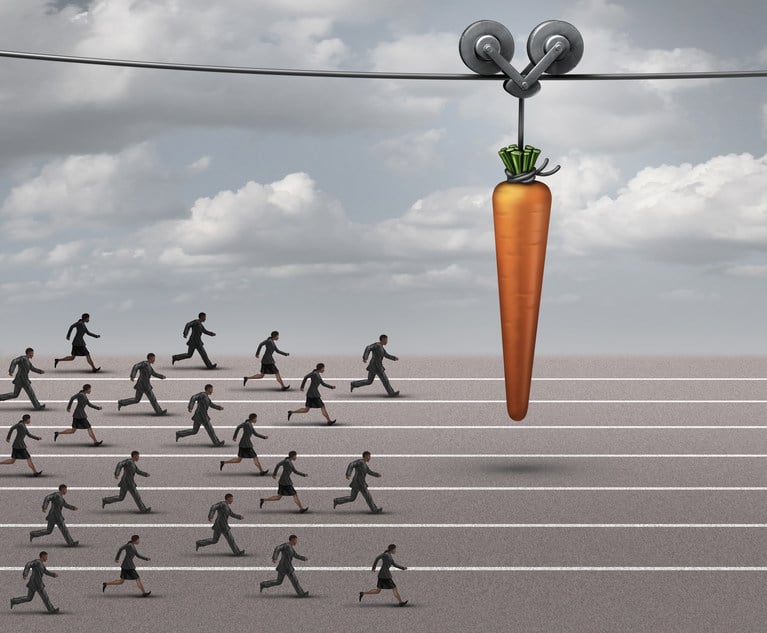

Many women returning from maternity leave are refused the flexibility they need to look after a young family and hold down a job. They are forced to resign. This is huge waste of talent and simply perpetuates the problem. I believe many employers discriminate, even at the pregnancy stage, because of ignorance and unfounded fears of what they can expect from the future.

The Law Society president Lucy Scott-Moncrieff recently remarked after a major Law Society survey that some law firms are "paying mere lip service to flexible working".

One of the recommendations that has emerged from the survey is 'embedding flexible working practices in corporate culture'. Scott-Moncrieff referred to firms losing talented women and promoting mediocre men. While some may not agree with this statement, it is an inescapable and uncomfortable truth that there are simply not enough women in senior level positions in law firms.

Firms need to think of more creative ways to retain women who are trying to balance family life with a career. The over-emphasis on billable hours is an outdated measure of performance. Shouldn't all skills be taken into account, rather than just time in the office? Firms could also focus more on compressed hours, job shares, working remotely, using teams of lawyers on cases and using support staff.

That way, in the words of Scott-Moncrieff, perhaps we can ensure that more women see the paintings on the boardroom wall.

Harriet Bowtell (pictured, top) is a partner in the employment department at Slater & Gordon.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to This Dark Horse US Firm in China?

Big Law Sidelined as Asian IPOs in New York Dominated by Small Cap Listings

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250