King & Wood Mallesons - the lessons for law firm leaders

What conclusions can be drawn from KWM's current predicament?

January 06, 2017 at 05:04 AM

5 minute read

King & Wood Mallesons (KWM) was never really a law firm. For starters, it was a verein – a structure that allowed three distinct firms to create a branding opportunity – King & Wood in China, Mallesons in Australia, and SJ Berwin in the UK. As things turned out, when SJ Berwin came on board in 2013, the verein whole quickly became less than the sum of its parts.

King & Wood Mallesons (KWM) was never really a law firm. For starters, it was a verein – a structure that allowed three distinct firms to create a branding opportunity – King & Wood in China, Mallesons in Australia, and SJ Berwin in the UK. As things turned out, when SJ Berwin came on board in 2013, the verein whole quickly became less than the sum of its parts.

As ALM's Chris Johnson and Rose Walker put it in their recent feature, a verein is: "A holding structure that allows member firms to retain their existing form. The structure… enabled the three practices to combine quickly and keep their finances separate."

But the structure also means that when one member of the verein hits hard times, the others can walk away. For KWM, "The Chinese and Australian partnerships have effectively been able to stand back and watch as the European practice burned."

To be sure, the verein structure exacerbates the firm's current difficulties. But before leaders of big non-verein firms become too self-satisfied, they might consider whether their own firms risk the same dangers now afflicting KWM.

As Johnson and Walker report, the firm's compensation system produced bad behaviour. KWM awarded client credit to the partner who physically signed the invoice. That effectively encouraged partners to refer work to rival firms, rather than other KWM partners.

Think about that last sentence for a minute.

"It was one of the things that killed the firm," says one former London partner. "If I sent work to other [KWM] partners, it would be out of my numbers at the end of the year. It was better for me to send it to another firm, as I'd then still be the one invoicing the client, so I'd get the credit for everything."

A team of one, not one team

When it came to cross-selling among offices and practice groups, management talked a good game. Indeed, the verein's 2013 merger tag line was 'The Power of Together'. But here, too, behaviour followed internal financial incentives. The compensation committee focused on individual partner performance, not the 'one team, one firm' soundbite on its 'vision and values' website page.

"There was a complete disconnect between what management said we should do and what the remuneration committee would reward us for doing," says a former partner.

Lessons not learned, again

As KWM's European arm disintegrates, most law firm leaders will probably draw the wrong conclusions about what went wrong. Emerging narratives include: SJ Berwin had been on shaky ground since the financial crisis hit in 2008; the firm lacked competent management; the principal idea behind the combination – creating a global platform – was sound; only a failure of execution produced the bad outcome.

For students of law firm failures, the list sounds familiar. It certainly echoes narratives that developed to explain the 2012 collapse of Dewey & LeBoeuf. But the plight of KWM – especially the SJ Berwin piece – is best understood as the natural consequence of a partnership that ceased to act like a partnership. In that sense, it resembles Dewey too.

The organisational structure through which lawyers practice law together matters. The verein form allows KWM to back away from the failure of the European partnership with limited fear of direct financial exposure. But as the legacy SJ Berwin business careens toward disaster, fellow verein members will suffer, at a minimum, collateral damage to the KWM brand.

What's the future worth?

The lesson for big law firm leaders seems obvious. Since the demise of Dewey, that lesson has also gone unheeded. A true partnership requires a compensation structure that rewards partner-like behaviour – collegiality, mentoring, expansion and transition of client relationships to fellow partners, and a consensus to pursue long-term strategies promoting institutional stability rather than maximising short-term profit metrics.

Firms that encourage lawyers to build individual client silos from which partners eat what they kill, risk devastating long-term costs. They're starving the firm of their very futures. Unfortunately, too many big law firm leaders share a common attitude: the long-term will be someone else's problem.

In a line that stretches back to Finley Kumble and includes Dewey, Bingham McCutchen and a host of others, the names change, but the story remains the same. So does a single word that serves both as those firms' central operating theme and as their final epitaph: greed.

Steven J Harper is an adjunct professor at Northwestern University and author of The Lawyer Bubble: A Profession In Crisis and other books. He retired as a partner at Kirkland & Ellis in 2008 after 30 years in private practice. He blogs about the legal profession at The Belly of the Beast, and a version of the column above was first published on that website. Follow Steven on Twitter at @StevenJHarper1.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

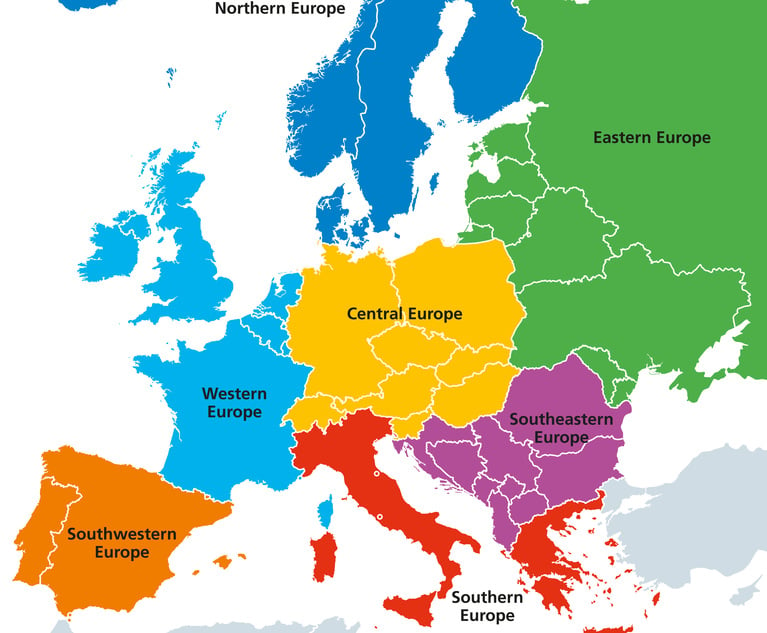

To Thrive in Central and Eastern Europe, Law Firms Need to 'Know the Rules of the Game'

7 minute read

GOP's Washington Trifecta Could Put Litigation Finance Industry Under Pressure

Trending Stories

- 1Gibson Dunn Sued By Crypto Client After Lateral Hire Causes Conflict of Interest

- 2Trump's Solicitor General Expected to 'Flip' Prelogar's Positions at Supreme Court

- 3Pharmacy Lawyers See Promise in NY Regulator's Curbs on PBM Industry

- 4Outgoing USPTO Director Kathi Vidal: ‘We All Want the Country to Be in a Better Place’

- 5Supreme Court Will Review Constitutionality Of FCC's Universal Service Fund

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250