Under the bonnet: an in-depth look at the financial health of the UK top 50

The LLP accounts for the UK's top law firms offer real insight into the challenges they face

May 25, 2017 at 06:25 AM

8 minute read

The limited liability partnership (LLP) accounts for the UK top 50 law firms, when scrutinised side by side, throw up so many potential metrics on which to compare performance, it can be hard to know where to start.

The latest analysis of the group's accounts, carried out on behalf of Legal Week by accountants Smith & Williamson, allows us to compare firms across everything from profitability, debt levels, capital ratios, pension liabilities and staff costs for the 2015-16 financial year.

And for the first time, this year we're also comparing performance across the group for three years – with the most recently available LLP figures set against 2014-15 and 2013-14.

Naturally, the figures need to be accompanied by a very significant disclaimer. The positive spin is that they allow like-for-like comparisons across a range of metrics that simply would not be possible through any other means.

The downside, though, is the caveat that a like-for-like comparison of figures in different firms' LLP accounts can be problematic, given that the same measures may hold a different significance for different firms.

Herbert Smith Freehills and Simmons & Simmons, for example, have high levels of borrowing, but these reflect their decisions to finance their activities primarily through third-party loans, rather than via partners taking on the debt individually through capital loans. Similarly, as demonstrated by Norton Rose Fulbright, borrowings do not necessarily mean the firm is in a net debt position, as it needs to be offset against cash in the bank.

Elsewhere, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer records some of the biggest declines across a host of profitability measures during 2015-16. Operating profit and profit available for division among members fell by around 24% year on year, but this plummet reflects a theoretical charge relating to annuity provisions for partners' future retirements. If you add back the £138.6m provision for annuities then its profit would stand at around £500m.

However, putting these caveats to one side, the accounts still highlight some very clear trends and areas of concern for some firms. So, from the thousands of numbers to choose from, what jumps out?

Pay rise warnings

Many of the numbers suggest firms have been taking positive steps to manage their finances. Only seven of the 48 top 50 firms filing LLP accounts posted year-on-year declines in revenue for that year, with 34 of the group having loans or overdrafts; with Eversheds having joined the 33 firms with borrowings in 2014-15.

There are, however, some warning signs. Not least the fact that the number of firms seeing a dip in operating profit rose from 13 in 2014-15 to 18 in 2015-16, with average operating profit ratio (operating profit compared with revenue) also declining marginally year-on-year.

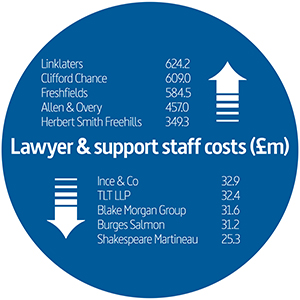

Arguably more concerning is that spending on lawyer and support staff salaries across the UK top 50 increased, with this increase coming alongside a corresponding year-on-year rise in the cost of salaries as a percentage of revenue.

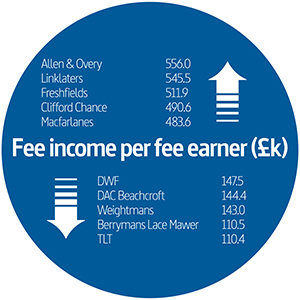

With these increases in salary costs coming alongside two years of slight declines in fee income per fee earner, the obvious concern for firms is whether they can really afford the annual pay rises that have become standard practice.

Giles Murphy, head of the professional practices group at Smith & Williamson, comments: "Firms can't afford the level of salary increases they're providing staff. It's a highly competitive market, but the concern is that firms are, at a basic level, becoming less efficient – their cost base is growing at a faster rate than income levels. A key element of cost base is people, and they somehow have to keep that under control."

The accounts show total staff costs across the group stood at more than £6bn, with this figure equating to an increase in average costs of 4.8%, against a rise of 3.6% in average headcount across the group.

The accounts show total staff costs across the group stood at more than £6bn, with this figure equating to an increase in average costs of 4.8%, against a rise of 3.6% in average headcount across the group.

With fee income per fee earner dipping marginally for the last two years, it is clear that fee income growth has not kept pace with these rising costs. Twenty-five of the firms included in the research saw fee income per fee earner either drop or stay static in 2015-16, compared with the previous year.

As Murphy adds: "Income per lawyer has declined for two years running, and that comes down to the efficiency point. A greater percentage of income firms are generating is being spent on the people they're employing, and that's flowing through to profitability and can't continue."

Given the accounts cover the 2015-16 financial year and therefore do not take into account the large associate pay increases introduced by many firms from May 2016, next year's accounts could paint a more worrying picture. And, crucially, this situation is unlikely to improve if firms opt to match the latest round of salary rises currently taking place across the London offices of some US firms when they confirm 2017 associate pay rates.

White & Case and Shearman & Sterling, for example, are now offering a base rate for newly qualified (NQ) lawyers of £105,000, compared with $180,000 (£139,000) at the likes of Latham & Watkins and other leading New York firms – both of which are significantly higher than the NQ rates currently offered by the magic circle.

With costs rising at all bar nine of the firms included in the research, those that have taken active steps to control their cost base stand out. Ashurst is the only top 15 UK firm to record a drop in staff costs during the year, with its 2% decline in costs coming against a 3% rise in staff numbers.

With costs rising at all bar nine of the firms included in the research, those that have taken active steps to control their cost base stand out. Ashurst is the only top 15 UK firm to record a drop in staff costs during the year, with its 2% decline in costs coming against a 3% rise in staff numbers.

At the other end of the scale, some of the firms seeing the largest increases in staff costs have seen their figures skewed by unique circumstances. Gateley, for example, saw staff costs leap by 79% to £39m as a result of its conversion from an LLP to a plc listed on London's AIM market. Meanwhile, Bird & Bird's 16% jump in staff costs is the product of exchange rate fluctuations when its figures were converted from euros into sterling.

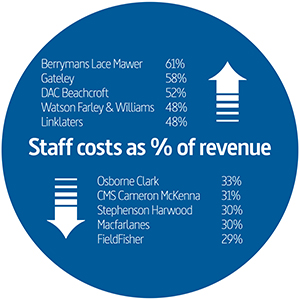

A slightly different view of how firms operate emerges when looking at their approach to staff costs. Many of the firms recording the highest staff costs as a percentage of revenue are well known in the insurance market. BLM, for example, pays out 61% of its revenue in salary costs, narrowly ahead of Gateley's 58% and DAC Beachcroft's 52%.

But Linklaters and Freshfields also shell out heavily on staff costs, with the former spending 48% of total fee income on staff costs and the latter paying out 45% of billings on staff salaries and other expenses.

In contrast, Allen & Overy paid out only 35% of revenue on its staff, while Fieldfisher and Macfarlanes round out the bottom of the table by paying out only 29% and 30% respectively on staff.

In contrast, Allen & Overy paid out only 35% of revenue on its staff, while Fieldfisher and Macfarlanes round out the bottom of the table by paying out only 29% and 30% respectively on staff.

Commenting on the trend, Jomati consultant Tony Williams warns: "Firms are getting higher revenues by adding headcount. Chargeable hours are not particularly high – firms are paying lawyers more, but they're not getting any more productivity from them, and that's squeezing margins.

"It's not clear if that's because of more fixed prices or people are working fewer hours, but there's certainly a problem there and it can't continue indefinitely – even though there is still a healthy margin."

Backwards steps

Another issue prompting some cause for concern is the lack of progress firms are making to bill efficiently and collect what is owed to them. Both client debtors and debtor days increased year on year, with the research highlighting significant disparities in how long it took firms to collect their dues. At Irwin Mitchell, for example, debtor days stood at 253 in 2015-16, compared with just 61 at Travers Smith.

It is an obvious area for improvement for some firms, and in an uncertain market – with concerns sharpened by King & Wood Mallesons' recent UK collapse – it is possible that lending banks may be less sympathetic towards law firm borrowers.

Smith & Williamson's Murphy comments: "The next 36 months will be a period of greater uncertainty, so it's important for firms to have a greater cash buffer to deal with these volatilities."

As Williams concludes: "Work in progress and debtors going the wrong direction is another cause for concern. What they say is true – 'revenue is vanity, profit is sanity and cash is king'. If they're not getting the cash in there's less to invest, and while you're on a decent margin that's an irritant more than a cause for concern – but you can potentially get yourself into trouble."

All the more reason for firms to take heed and speed up the process of restructuring their businesses to make better use of technology and cheaper non-lawyers.

- Click here for the full table of LLP figures

- The warning signs firms should be looking out for: lessons from the UK top 50 LLP accounts

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Big Law Sidelined as Asian IPOs in New York Dominated by Small Cap Listings

X-odus: Why Germany’s Federal Court of Justice and Others Are Leaving X

Mexican Lawyers On Speed-Dial as Trump Floats ‘Day One’ Tariffs

Threat of Trump Tariffs Is Sign Canada Needs to Wean Off Reliance on Trade with U.S., Trade Lawyers Say

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

- 2Litigators of the Week: A Directed Verdict Win for Cisco in a West Texas Patent Case

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Womble Bond Becomes First Firm in UK to Roll Out AI Tool Firmwide

- 5Will a Market Dominated by Small- to Mid-Cap Deals Give Rise to a Dark Horse US Firm in China?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250