Money talks, partners walk: how the pay gap between elite US and UK firms became a chasm

The US elite comfortably outstrip top UK firms on profitability - what are the key factors behind this huge disparity?

June 12, 2017 at 02:37 AM

19 minute read

An underappreciated effect of the Great Recession is how it put on steroids the amounts by which elite US firms can outflank their UK counterparts on partner compensation.

As a consequence of higher profitability and wider compensation ranges, the most highly compensated partners at elite US firms now earn up to three times as much as their counterparts at traditional UK lockstep UK firms.

Unsurprisingly, we are seeing an almost one-way flow of lateral partners. As talent flows, competitiveness follows, leaving the UK elite facing the prospect of a downward spiral through the global rankings. And to think: it all began with the accident of geography.

The Great Recession

The onset of the global financial crisis dealt a body blow to global law firms. Average profit per equity partner (PEP) fell 15% in one year for the elite on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, since the initial drop, the fortunes of UK and US firms have differed sharply. This graph (click to view) shows the profitability performance through the Great Recession of the magic and silver circle firms and the 10 US firms with the highest PEP.

While almost a decade later, the elite UK firms have yet to regain their pre-recession profitability levels, the US elite regained their prior peak in just three years and are now enjoying profitability some 20% above that level (each on an inflation-adjusted local currency basis).

The US firms are exhibiting growth and institutional vitality that their UK counterparts are not

This marked difference in performance is not just in profitability, manufactured, say, by constrained equity partner numbers. Indeed, as this graph shows, firms on both sides of the Atlantic increased their number of equity partners through the recession, with the US firms doing so slightly more than their UK brethren.

However, the trajectories of the number of lawyers are quite distinct: the US firms have grown strongly while the UK firms have contracted slightly, leading to leverage moving in opposite directions on either side of the Atlantic. Thus, the US firms are exhibiting growth and institutional vitality that their UK counterparts are not.

Today's profitability and compensation disparities

It is useful to try to understand today's differences at the individual firm level. This is an inexact science. The US firms' financial data are unaudited self-reported numbers and, while the UK firms have publicly available audited reports, and some are clear throughout (e.g. Allen & Overy), others are quite obscure in places (e.g. pensions). Further, idiosyncratic approaches to counting the number of equity partners appear common on both sides of the Atlantic. Thus, what follows is reliable more in terms of trends and order-of-magnitude differences than it is in the particular.

Accepting these PEP data for what they are, they need to be brought to the same currency for comparison. Using market exchange rates can be misleading. Instead, the comparison shown in this graph uses long-term equilibrium exchange rates (see Equilibrium Exchange Rate Comparison footnote, below). With the exception of Slaughter and May, the low profitability end of the US elite is operating at PEP levels some 30%-60% above their UK counterparts.

The differences in average profitability will tend to understate the differences in compensation for established partners. For this comparison, compensation ranges within firms play an important role. US firms are increasingly moving to systems wherein individual partner compensation more closely reflects the wide range in the economics of different partners' practices. This has led to US and UK firms having very different ratios between the compensation of partners in their highest and lowest compensated equity partner bands.

Last December, for example, Kirkland & Ellis moved from an 8:1 to a 9:1 ratio between the comp of their top and bottom bands; UK firms traditionally operate at about a 2.5:1 ratio.

Last December, for example, Kirkland & Ellis moved from an 8:1 to a 9:1 ratio between the comp of their top and bottom bands; UK firms traditionally operate at about a 2.5:1 ratio.

So how big is the compensation difference at the top end? Well, here's a way to estimate it: for a 9:1 firm, a reasonable rule of thumb is that the lowest compensated partners earn about one third of firm average while the top tier earn about three times firm average. Similarly, for a 2.5:1 lockstep firm, a reasonable estimate of the range is from 0.60-0.65 to 1.5-1.6 times firm average. Applying these ratios to an idealised US firm with average compensation 30% higher than an idealised UK firm, we get that compensation at the top end of the US firm is 2.5 times that at the UK firm.

This comparison explains why many UK firms have gone off lockstep at the high end. How far off have they gone? In the Companies House filings of the magic and silver circle firms, the highest ratio of top to average compensation identified was 2.3 times. Does this close the gap? Yes, but not entirely – the gap contracts from 2.5 times to 1.7 times, i.e. compensation at the top end of a 9:1 US firm would be 70% above that at the widest modified lockstep UK firm.

The power of geography

To explore how UK firms could close the compensation gap, it's useful to consider how there can be such a divergence in PEP when both sets of firms have great lawyers, doing highly sophisticated bespoke work on critical matters for clients that value high quality lawyering.

Failure by the UK elite to adapt will set them on a course to mediocrity

A part of the explanation is geography. Different geographic markets have different inherent profitability: while the US and UK are high profit, much of the rest of the developed world (e.g. western Europe, developed Asia, the Middle East and Australia) operates at a notch down in profitability, and the emerging markets (e.g. Africa, China, CIS, Latin America) operate at yet a further notch down. The UK and US elite firms have very different footprints across geographic markets categorised as high, medium, and low profitability in this way (click here to see this illustrated).

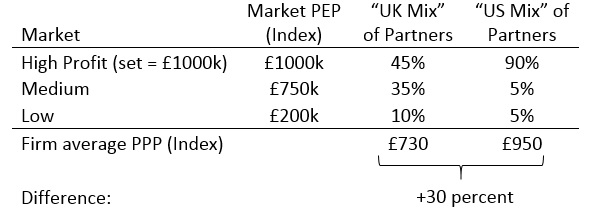

What would you have to believe for the geographical footprint difference to explain the divergence in PEP? Well, if you estimate that profitability of the medium and low profit markets is 75% and 20%, respectively, of that of the high profit markets then, for the typical UK and US mixes of partners by market type as shown below, the mix differences would explain a 30% difference in PEP:

This difference in footprints, and its profitability consequence, is probably more due to 'maps than chaps' – that is, more due to geographic happenstance than to prescient leadership. For a US firm, sitting in an economy that is more than 6.5 times the size of that of the UK, much of the impetus for growth can be satisfied within the domestic market. As the segment of the US market in which these elite firms play is largely homogenous nationally, growth comes without a major profitability sacrifice. In contrast, the UK firms' natural avenues for growth – continental Europe, Hong Kong, Australia – all entail a step down in profitability.

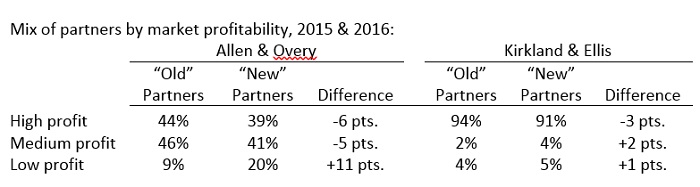

Geographic growth has some underappreciated dynamics. One is that once a foothold is established in a market, the number of partners in the market tends to grow at a faster rate than does that of the firm as a whole. We see this in how the mix of 'new' partners (promotions and laterals) differs from that of 'old' partners across markets by profitability type; see data for an example UK and US firm below:

Growing disproportionately in lower profit markets reduces average profitability, with the effects more pronounced in absolute terms as the proportion of a firm's partners in the lower profit markets grows. Such disproportionately lower profit growth is rarely a firm's intent. More typical is an aspiration to be the minimum size needed to serve the firm's most important clients in the local market.

But mission creep often ensues. The entrepreneurial type of partner who founds an office in a new geography will instinctively and energetically look to grow. Growth won't always be in practices, or with clients, that are central to the firm's strategy. Yet, to firm leadership, sanctioning the hiring of each marginal lawyer seems like a small price to pay to keep the entrepreneurial founders engaged and motivated. Before long, however, the firm's low profit market presence is larger and less focused than was intended.

Strategy implications

There are major differences in strategy among the global elite. For example, Wachtell and A&O are pursuing very different approaches to securing sustainable, above normal, profitability. Different strategies necessarily produce different levels of average PEP. This is not of itself a problem; it only becomes a problem if a firm's compensation system creates a significant and sustained disconnect between the economic value of a partner's practice and the partner's compensation. If the comp system tends to move individual partners' compensation toward global averages (as can happen out of a 'one firm' ethos), then the comp of partners in lower profit markets drifts up while that of partners in higher profit markets drifts down and leads to their being undercompensated relative to the economic value of their practices. The higher the percent of firm's partners in lower profit markets, the more pronounced is this effect and hence the greater is the risk of a firm's most commercially successful, high profit market partners departing to firms prepared to share with them more of the economic value created by their practices.

While many UK firms have increased significantly the variability in their compensation systems (e.g. different ladders by country, uncapped top tiers), there is evidence that such talent migration is happening between the UK and US elite. I looked back at partners who had moved from an elite US firm to an elite UK firm, and vice versa, during the past five years. What I found was a total of 35 such moves: 29 were from the UK elite to the US elite; six were in the opposite direction.

The difference is wider in each group's home market: 14 partners moved from the UK to the US elite in London; two moved from the US to the UK elite in the US. Lateral movement was especially robust last year – 2016 accounts for almost half of the five-year total. The hiring by US firms is concentrated in just three US firms – Kirkland & Ellis, Gibson Dunn & Crutcher and Davis Polk & Wardwell accounted for 25 of the total hires (click here to see more).

For a US firm, sitting in an economy that is more than 6.5 times the size of that of the UK, much of the impetus for growth can be satisfied within the domestic market

Much of conventional economics is premised on the notion of diminishing marginal returns; that is, the tendency for companies that get ahead of their rivals to be slowed in their progress by running out of, say, the best land to farm or people to hire. Law firms defy this convention. Rather, they are governed by the phenomenon of increasing returns, that is the tendency for firms who get ahead to get further ahead as virtuous loops are established between attractive clients, great lawyers and strong profits. We see this increasing returns phenomenon among elite global firms; the firms with stronger PEP have exhibited higher growth in PEP than have their lower PEP brethren.

The evidence is clear that the US elite are ahead, and getting further ahead, of their UK counterparts not just in terms of PEP but also, more fundamentally, in attracting excellent lawyers in high profit markets and in overall organisational vitality. It would be tempting for the UK elite simply to accept this and to carry on unperturbed and undaunted – tempting, but foolhardy. Competitors don't stand still. The US second tier stands ready to assail the UK elite with the same combination of partners concentrated in high profit markets and wide compensation bands that was so successfully exploited by its elite compatriots. Unaddressed, successively lower tier US firms will surpass the erstwhile UK elite as the latter recede into mediocrity.

Thus, it behoves the UK elite to take stock of where they are setting the balance on a number of strategy levers. While the action implications from such deliberation will vary by firm, common themes will likely include the following:

Compensation systems: A compensation system seeks to balance a firm remaining true to its traditions with the changing realities of the external marketplace. On the latter, a firm with a narrow compensation range is increasingly competing with one hand tied behind its back in the market for talent. Too narrow a compensation system also risks muting partners' motivation in an increasingly challenging environment where success can accrue disproportionately to the more motivated. Compensation systems can be changed without unduly damaging the fabric of a partnership by following, for example, a process that engages all partners in an open dialog .

Partner mix across markets of varying profitability: An overly strong presence in lower profit markets reduces overall profitability, pressures compensation systems, and can foment disharmony among partners. Firms may want to consider selective withdrawal from, and slowing promotions and laterals in, lower profit markets. In principle, UK firms could raise their average profitability in one step through a combination with a US firm. In practice, it's not clear that the UK elite would be enthusiastic about combining with the US firms within comparable bands of profitability, (e.g. Freshfields and Linklaters would rank in the 20s of the AmLaw 100 by PEP; Clifford Chance, Allen & Overy, and Macfarlanes would rank in the 30s). A more viable approach to raising profitability through growth in the US may be to focus on sub-segments of the broader service areas where the UK firms have unsurpassed strength and then look to grow around these.

Growth rate: The public company world attaches great importance to growth. This makes sense: shareholders benefit from stock price appreciation resulting from equity markets believing future revenue streams will exceed the outlays necessary to create them. The law firm world is very different in two ways. Firstly, shareholders only benefit from the year-by-year realisation of the incremental profits – there is no realisable benefit today of anticipated future incremental profits. Secondly, there is a cap on the amount by which the incremental profit created by, say, a successful lateral partner can exceed their compensation – if too wide a gap emerges, the risk of the partner leaving grows. Thus, law firms should be chary of the clarion call to growth that permeates the broader business world.

This is not to say that law firms should eschew growth. Indeed, there is a minimum required growth rate: that needed to promote associates to partners at a rate sufficient to attract high quality associates. Above this rate, growth should be focused on tightly integrated initiatives that enable the organisation as a whole to realise economic value today (through, say, more differentiated offerings that enable strengthened price realisation); firms should avoid growth through non-integrated initiatives that putatively will result in future revenues significantly in excess of their costs.

Investment horizon: In the broader business world, it's common to espouse investing for the long term, that is to put money into initiatives that will not yield a profit until many years in the future. One has to be thoughtful in adopting such an investment horizon in the law firm world. Investments at law firms entail paying partner A less than the economic value of her practice so you can pay partner B more than the value of his. If such differences are large or sustained then commercially productive partners become disenchanted, lose motivation, and leave to firms prepared to pay them more. In the case of lateral partner investments, this risk is compounded by the fact that 45% of laterals do not stay more than five years, meaning there is almost a 50/50 chance the investment outlay is simply wasted. There is no comparable constraint in the broader business world – a 'cash cow' can fund 'question marks' indefinitely. This is not to say law firms should not invest. Rather it is to say that law firms should set a time horizon for realising an economic value from investments that is shorter than that encouraged in the broader business world.

Revenue vs profit: Law firms seem to have been misguided about the importance of revenues. Law is a two-sided market – firms compete for the most attractive clients and for the best lawyers, with success in one enhancing the prospects for success in the other. Revenues may be proof that clients are being attracted to a firm, but profit is what attracts and retains great lawyers. It's always harder to build profit than revenue. When growing, the hurdle should not be 'can we sell more work?'; rather it should be 'can we increase our realised price by offering something clients truly value and that few, if any, others can match?'.

Bundled vs integrated service offerings: Law firms succeed when their service offerings are truly differentiated – differentiation translates to fewer credible competitors, and fewer competitors leads to stronger price realisation and hence profitability. A major reason firms build broad office networks is to create service offerings that span offices and hence are differentiated.

There are some basic truisms that must be honoured for this logic to be valid. First, a firm has to serve the same clients with the same offerings across the broad office footprint; this isn't always the case as local offices have a proclivity to serve local clients. Also, the bundle has to be valued by clients. This isn't always the case either. For example, a client will not always use the broad-footprint firm when they want the best-of-breed lawyer in a particular jurisdiction. It's useful to parse through the implicit 'when best-of-breed not required' rationale here: this is equivalent to a client using the broad-footprint firm when they are happy with a second best local lawyer, suggesting the client would probably have been happy with an arms-length independent firm. There is an inherent tension between this implicit rationale and the broad-footprint firm's typical aspiration of being an elite law firm.

Where the broad office footprint can lead to differentiation is when it is used to create integrated, not just bundled, offerings. An integrated offering is one where lawyers with different domain expertise and backgrounds work intensively together to develop solutions that wouldn't be developed if they simply worked together across firm boundaries. It's stunningly difficult to pull off this integration at law firms. This is partly because many partners don't distinguish between cross-selling and integrating offers. Cross-selling is the law firm equivalent of a fast food upsell ('do you want fries with that?'); an integrated offering is lawyers from different backgrounds working on the same matters and on developing new legal specialities at the interstices of extant practice area definitions. Creating such offers doesn't happen naturally. It requires enablement, example setting and relentless encouragement from firm leadership, and the client-teaming and practice-management overlays to a firm's office-centered organisational structure.

This is a watershed moment in the life of elite UK firms. Their US counterparts, whether through happenstance or prescient leadership, have moved ahead in terms of profitability, vitality and ability to attract great partners. The US second tier stands ready to replicate the success of its elite compatriots. Failure by the UK elite to adapt will set them on a course to mediocrity. The tide is at the flood; fortune, or shallows and misery, beckons.

Hugh Simons is a strategist and veteran professional services firm leader. He is a former senior partner, executive committee member and chief financial officer at The Boston Consulting Group and the former chief operating officer at Ropes & Gray.

***

Footnote: Equilibrium Exchange Rate Comparison If you compare the profitability of elite UK and US firms using market exchange rates, you get numbers that tell you more about the vagaries of exchange rates than they do about the firms' relative performance. Instead, this analysis uses purchasing power parity (PPP) rates as published by the OECD. These PPP rates remove the effects of capital flows and currency speculation by looking simply at the exchange rate required to have the same basket of goods cost the same amount in each country. PPP rates are stable over time and serve as a long-term equilibrium about which market rates vary. They ring true as reasonable equilibrium rates: for example, while the average FY 2015-16 rate for the Euro was 1.355 €/£, the equilibrium rate is 1.088 €/£. These rates are used in place of market rates in two steps: (1) the GBP-denominated profitability of the UK firms is restated using information about the sensitivity of this profitability to exchange rate variation provided in Companies House filings, (this adjustment materially increases GBP-denominated profit per equity partner for firms with significant Euro-denominated practices), and (2) the dollar-denominated profit per equity partner of the US firms is converted into GBP at the equilibrium GBP/USD rate of $1.452/£ to enable a same-currency comparison.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

KPMG Moves to Provide Legal Services in the US—Now All Eyes Are on Its Big Four Peers

International Arbitration: Key Developments of 2024 and Emerging Trends for 2025

4 minute read

The Quiet Revolution: Private Equity’s Calculated Push Into Law Firms

5 minute read

'Almost Impossible'?: Squire Challenge to Sanctions Spotlights Difficulty of Getting Off Administration's List

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250