What is really behind Freshfields' poor financial results?

Amid standout performances from its magic circle rivals, Freshfields appears to have had a disappointing 2016-17 - but why?

July 10, 2017 at 06:45 PM

7 minute read

The UK law firm reporting season is now well underway. The story so far has been one of unlikely financial gains, with challenging Brexit-related market conditions masked by the effects of a significantly weakened pound.

The numbers of the more international UK-based firms in particular have been heavily skewed, with foreign revenue artificially boosted as it is converted into sterling for consolidated accounts. Some firms have seen their revenue inflated by as much as 10 percentage points on that basis alone.

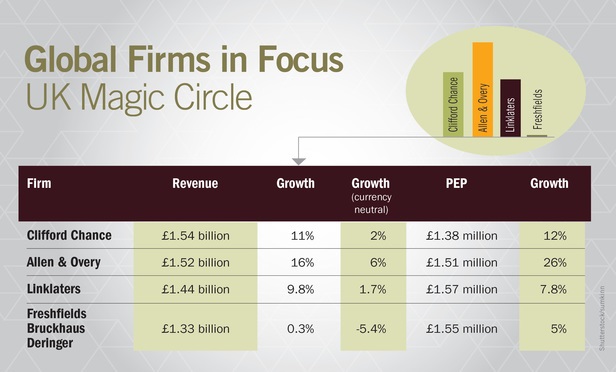

One notable exception is Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, which struggled to even maintain its revenue in what the firm described as "a challenging year", despite a hefty currency bump. The firm's revenue inched up just 0.3% in sterling terms during the past 12 months, to £1.33bn. Remove the currency effect and it would have fallen by 5.4%

Freshfields' magic circle rivals, in comparison, each posted massive revenue increases of between 9.8% and 16%.

Joint managing partner Stephan Eilers blamed the results on several senior partners having retired or left the firm, including corporate rainmaker Mark Rawlinson's move to Morgan Stanley as chair of UK investment banking last October. He also pointed to a loss of fees due to conflicts, and the collapse of the merger between the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and Deutsche Boerse, as Freshfields had been advising the LSE on the deal.

But that doesn't seem to tell the whole story. Taking the gains achieved by its magic circle rivals as a baseline, Freshfields' lack of growth represents a loss in revenue of between £130m and £210m. Partner exits and conflicts can be costly, it's true. But they are issues that affect all large law firms.

The other magic circle firms will also routinely face conflicts that may cost them some lucrative mandates. The level of conflicts activity will vary year by year, of course, but that still doesn't adequately explain Freshfields' performance relative to its rivals.

Likewise, while Freshfields did lose some big-name partners last year – particularly to US competitors – they were also hardly alone on that front. And retirement is a constant, ongoing issue that firms should be dealing with as part of proper succession planning.

Finally, Eilers referred to various investments made by the firm during the last financial year, such as the continued development of its US offices, which in recent years have grown via a number of splashy hires. It also made reference to its Manchester legal and business services centre, which opened in 2015 and now employs almost 600 staff. Such investments will have eaten into the firm's margin to a certain degree, but should only have added to its revenue. You wouldn't expect an investment to generate immediate returns, but if it causes revenue to fall, something has gone very badly wrong indeed.

So, what else could be to blame?

Freshfields is marginally less international than the other three firms – 42% of its lawyers are based in the UK, compared to 38% at Linklaters, 36% at Allen & Overy (A&O) and just 29% at Clifford Chance (CC), according to Global 100 data – and is therefore likely to have received less of a boost from foreign revenue. It also means that Freshfields is slightly more exposed to a UK market that has proved decidedly patchy ever since the Brexit vote. The subsequent decline in transactional activity – the volume of UK M&A deals dropped to a four-year low in the first six months of 2017, according to Mergermarket data – will no doubt have had an impact on a firm best known for its market-leading corporate and M&A practice.

Also notable is Freshfields' massive exposure to the highly challenging German market. Freshfields has one of the largest presences of any law firm in the country – even including domestic German firms – with more than 500 lawyers and no fewer than five offices.

International law firms have found their finances squeezed in Germany by a combination of severe pricing pressure from clients – particularly listed German companies – and extremely high salary costs. Lawyers are paid more in Germany than almost anywhere else on earth, apart from New York.

Things have come to a head in the past 12 months, with each of the magic circle firms investigating ways to combat the tightening profit squeeze. To that end, Freshfields is planning to cut its German partnership by up to 20% by 2020, while CC and Linklaters have both introduced compensation caps for partners in the country. Despite this, a Freshfields source who did not wish to be identified told The American Lawyer that the firm's German practice actually had a "pretty strong year", and that things were instead "a bit softer across the board".

The firm has responded to changing market conditions by rebalancing its practice – downsizing in finance, for example – and has also seen an unusually high number of retirements from its ageing partnership, the source said. The size of the firm's partnership is likely to continue to contract during the coming years without causing a fall in revenue, the source added, leading to continued growth in profit per equity partner (PEP).

That changing internal demographic already played out in the results for the last financial year. The roughly 6% reduction in equity partner numbers meant that while net income fell slightly, PEP still increased by 5% to £1.55m.

Indeed, viewed from a broader perspective, Freshfields' results are clearly disappointing, but hardly catastrophic. Revenue provides an important indication of a business's performance – particularly when tracked over a number of years – but most would agree that profit is more important. After all, it's revenue for vanity, profit for sanity, as the saying goes. And on that measure, Freshfields is still firmly at the head of the UK pack, just £20,000 below Linklaters, the magic circle's new leader by that metric.

(The weak sterling means that even Linklaters would only have ranked 32nd by that metric in US dollars in this year's Am Law 100, however, providing a stark illustration of the difficulties UK firms face in competing with American rivals for lateral hires.)

Still, increasing profits by reducing equity partner numbers is clearly not sustainable in the longer term. Freshfields will be hoping that its investments in the US and elsewhere start to bear fruit in the form of renewed growth.

For now, the firm has been overtaken in the revenue charts by both A&O and Linklaters. Having previously ranked second among its magic circle peers by revenue, Freshfields is now £110m adrift from the group and a full £210m behind CC.

A&O's performance was particularly impressive, capped by a 16% increase in revenue and a 26% jump in PEP. The spectacular results, which look strong even in currency-neutral terms, were widely expected after the firm announced record growth at the half-year mark.

CC also achieved double-digit gains in both revenue and PEP – and its results could actually have been even better. Sources at the firm said that it front-loaded some costs into last year's accounts – including those relating to partner exits and the reorganisation of its Southeast Asia practice, which saw the firm withdraw from Indonesia and Thailand – and that its PEP would otherwise have topped £1.4m. CC declined to comment.

It is, of course, unwise to draw too many conclusions from a single year's results. We won't know until next year whether these fascinating figures are merely a reflection of a short-term blip or the beginning of a strategic divergence among historic rivals.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

KMPG Moves to Provide Legal Services in the US—Now All Eyes Are on Its Big Four Peers

International Arbitration: Key Developments of 2024 and Emerging Trends for 2025

4 minute read

The Quiet Revolution: Private Equity’s Calculated Push Into Law Firms

5 minute read

'Almost Impossible'?: Squire Challenge to Sanctions Spotlights Difficulty of Getting Off Administration's List

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250