What happens to Kirkland's legions of salaried partners?

Most salaried partners - or 'non-share' partners, as Kirkland call them - will not go on to make the equity at the firm. So what happens to those who do not make the cut?

October 12, 2017 at 03:59 AM

5 minute read

Last week Kirkland & Ellis announced that 97 lawyers had joined its salaried partnership, including 13 in London – the firm's largest-ever City promotions round.

That salaried partnership tier is relatively welcoming – both compared with other top US law firms, and especially compared to Kirkland's equity partnership.

Consider this: Kirkland had 359 equity partners last year, according to The American Lawyer's reporting. The firm currently lists about 975 total partners.

The simple fact is that most salaried partners – or "non-share partners" in Kirkland lingo – will not go on to reap the windfall that comes with an equity stake in the high-powered firm. But just how many non-equity partners don't make the cut? And what happens to them?

Past reporting by The American Lawyer has described the Kirkland partnership as an "up-or-out" model, with roughly 20% of salaried partners joining the equity tier after they become eligible about four years into their salaried partner tenure.

But an analysis of past salaried partner classes suggests that Kirkland's so-called sharp elbows may not be all that pointed. The American Lawyer researched the current jobs of the 315 lawyers that Kirkland announced as incoming partners between 2010 and 2013.

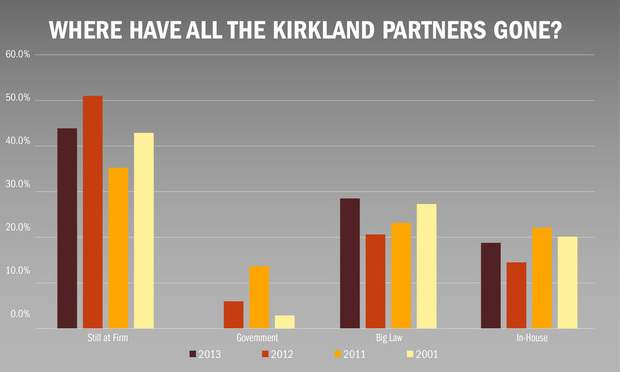

Of the 316 partners promoted during that four-year period, 43% remain at the firm. The analysis found that 43% of the 70 salaried partners made up in 2010 are still at Kirkland. The 2011 class, which featured 82 lawyers, has winnowed to 29, or 35%. Half of the 84 partners made up in 2012 are still at the firm. And 44% of the 2013 class remains at Kirkland.

While more lawyers enter Kirkland's salaried partnership every year than almost any other firm, the position at Kirkland is less of a long-term play than at other firms. Jones Day's partnership is comparable only insofar as it promotes a relatively high number of lawyers every year. In 2012, the firm promoted 45 lawyers to what it states is a "one-tier" partnership. Today, 73% remain at the firm.

The most common landing ground for Kirkland's income partners is at other Am Law 200 firms. Across the four Kirkland income partner classes analysed by The American Lawyer, roughly a quarter of those lawyers are now practising at other firms, according to those firms' websites, state bar registrations and individual profiles on professional networking website LinkedIn. Two of the most common firms for Kirkland refugees are King & Spalding and Sidley Austin.

After other jobs in Big Law, the second most common role after a Kirkland salaried partnership is an in-house position. That is where about 21% of former Kirkland lawyers end up. These are often high-ranking positions, with 13 partners from just four years' worth of salaried partner promotions now occupying chief legal officer or general counsel roles. The list of companies that now employ Kirkland partners as in-house lawyers includes Amazon, Boeing, Hulu, Intel, Johnson & Johnson, Kate Spade & Co, Koch Industries, McDonald's, Sony, Target, and more than a dozen others.

Government jobs – ranging from assistant US attorneys to administrative judges at the US Patent and Trademark Office – are the third most common, with less than 10% of lawyers taking a government paycheck. A sprinkling of lawyers start their own firms, become entrepreneurs in business or go into academia.

There are also significant gender disparities in the jobs data. The gaps show up mostly in three places.

First, men are more likely to be promoted to salaried partner than women, with 69% of the 316 partners promoted at Kirkland over the four-year span being men. That is roughly in line with the percentage of non-equity partners that are women – about 30% – according to the latest survey by the National Association for Women Lawyers. (The highest percentage of women promoted to salaried partner in a single year of those analysed at Kirkland was 2011, when 38% of new partners were women.)

Second, men are also more likely to stay at Kirkland than women. Of the 99 women promoted to salaried partner in the four-year period analysed by The American Lawyer, 31% are still at the firm. Of the 217 men promoted in that same timeframe, 47% remain at Kirkland.

Thirdly, women are more likely to work in-house than men after leaving Kirkland. About 30% of the women who have been promoted to partner at the firm are now working in-house, compared to about 18% of men. In recent years, Kirkland has invested in programmes that help lawyers at the firm find their next job, while also trying to strengthen bonds between the firm and its impressive list of alumni.

For instance, Kirkland launched a training programme aimed at teaching its associates and alumni about in-house career paths. Thirty participants attended seminars from December to March of this year that included panel discussions with current in-house lawyers. Kirkland said the goal of the programme is to prepare lawyers for future transitions to in-house roles and to support women who used to work at the firm in their effort to return to practising of law.

Kirkland did not immediately return a request for comment about the data. In the past, the firm's management has attributed the turnover in its partnership as a necessary byproduct of turning itself into a global legal giant.

According to the most recent Am Law 100 rankings, Kirkland trailed only Latham & Watkins as the world's most profitable firm when measured by gross revenue. Kirkland came in at fifth place when measured by profits per equity partner.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

X-odus: Why Germany’s Federal Court of Justice and Others Are Leaving X

Mexican Lawyers On Speed-Dial as Trump Floats ‘Day One’ Tariffs

Threat of Trump Tariffs Is Sign Canada Needs to Wean Off Reliance on Trade with U.S., Trade Lawyers Say

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Reviewing Judge Merchan's Unconditional Discharge

- 2With New Civil Jury Selection Rule, Litigants Should Carefully Weigh Waiver Risks

- 3Young Lawyers Become Old(er) Lawyers

- 4Caught In the In Between: A Legal Roadmap for the Sandwich Generation

- 5Top 10 Developments, Lessons, and Reminders of 2024

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250