Chinese law firms are poaching top talent from their global counterparts, and now they're coming after your partners.

Since early 2017, leading domestic players such as Fangda Partners and Han Kun Law Offices have been moving aggressively, hiring partners from the likes of Linklaters, Clifford Chance (CC), White & Case and Morgan Lewis & Bockius.

"Domestic Chinese firms have become increasingly active in recruiting from international firms," said Jason Ji, managing director of Singapore-based legal recruiter JC Consulting.

In January of this year, Shanghai-based Fangda – a firm that reported $136.5m in revenue in 2016 – announced that it had hired long-serving Linklaters partner and China head Fang Jian. Fang was the second former China management partner to be snapped up by Fangda from Linklaters in less than a year; six months earlier, Zili Shao, the magic circle firm's former Asia head, joined the Chinese firm as a non-executive chairman.

Beijing-based Han Kun also has been notably active in the Asia lateral market. Last year, it convinced former CC financial regulatory partner Yang Tiecheng to join the Chinese firm with most of his team in Beijing and Shanghai. And that was after the firm's earlier recruitment of former White & Case China chief Li Xiaoming.

For Fangda, Han Kun and other Chinese firms, the hiring of experienced partners from international firms is a logical next step in their quest to become major players in the global legal market. Not only do those lawyers give them more access to large, multinational clients, but they also help them serve their existing Chinese clients, many of which have become technology giants in their own right and have new and increasingly complex needs.

"Some of our clients have a very different status in the market today compared to 15 years ago," said Dafei Chen, a Hong Kong-based partner with Han Kun. "As their law firm, how can we stay unchanged?"

Indeed, when Han Kun was founded in 2004, the firm focused almost exclusively on venture capital and private equity. But many of its Chinese startup clients – companies like Shenzhen-based Tencent – have prospered during the past decade, growing into technology giants worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

The fundamental driver behind this rapid growth was the high-speed economic development that occurred in China during the past two decades. And that growth is now making domestic firms such as Han Kun more attractive to Chinese lawyers working at global firms, Chen said.

Top Chinese firms no longer market themselves with low prices; they want to be known for service quality

Regulatory restrictions that prevent international firms from practising Chinese law, combined with the relatively small size of global firms' Asia outposts, means lawyers at global firms with Chinese client connections are gradually encountering more and more roadblocks.

"Clients have various needs for legal services, and a domestic firm may better be able to handle some of those services," said Chen, noting that Chinese firms usually have a full-service offering, making it easier for them to keep a client's business within the firm.

To be sure, elite Chinese law firms started poaching from global firms more than a decade ago, as they sought experience in cross-border matters as well as knowledge in law firm management. Most of those hires consisted of mid- to senior-level lawyers who spent years training and practising with global firms but for various reasons were never made partner.

Shanghai-based Fangda and Beijing-based Haiwen & Partners have both expanded over the years with such hires. In 2007, for example, as part of Fangda's efforts to build its Beijing office, the firm recruited intellectual property litigator Gordon Gao from Paul Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, where he was of counsel. Gao has since led a successful IP disputes practice at Fangda and became one of the firm's top billers.

And more recently, in 2016, Haiwen recruited former Latham & Watkins counsel Lu Guiping, a Hong Kong and US-qualified capital markets specialist, and eventually launched a Hong Kong office in 2017.

Even at the partner level, Chinese firms have occasionally lured away top lawyers with western experience, filling a need as more and more of their work involved cross-border transactions. In 2004, for example, legacy King & Wood Mallesons made one of the earliest such moves by convincing longtime Vinson & Elkins Beijing chief representative Handel Lee to join as chairman. In the next few years, King & Wood continued with high-profile hires, including such notable partners as former CC Beijing chief representative Rupert Li and former Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman Shanghai managing partner Meg Utterback.

In addition, Robert Lewis left legacy Lovells, where he was Beijing managing partner, to join Shanghai-based Allbright Law Offices in 2010. He then moved on to Beijing-based Zhong Lun Law Firm in 2011.

During the past five years, the trend quieted down as China's domestic firms matured and grew stronger financially. However, there were still some exceptions – Fangda, for example, nabbed Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer's former China antitrust head Michael Han in 2014.

"The Chinese firms are much pickier now in making lateral hires," said one lawyer who has seen the changes firsthand. "[They] are less likely to hire people without a solid book of business."

Top domestic Chinese firms have seen substantial financial growth. Han Kun, for instance, reported profits per partner of $1.44m among 30 equity partners in 2016. But recruiters and lawyers alike said money is not the biggest selling point for Chinese firms.

"Money is not what draws partners from foreign firms to Chinese firms, despite their growing financial capability," said Shawn Chen, who leads the China business for London-based legal recruiter SSQ.

In fact, global firm partners may make less money immediately after making a move to a Chinese firm, he said. But the value they get in experience and reputation could help them build another career at a domestic firm.

"Eventually [the financial return] will catch up if you bring in enough revenue," he said.

Meanwhile, the Chinese firms see the investment made to lure global firm partners paying off in terms of what the new partners bring in reputation and experience, he said.

Indeed, JC Consulting's Ji said Chinese firms that have made recent hires from global firms were not driven to do so by the promise of instantly adding to their firm's overall wealth. After more than two decades of steady growth, many domestic firms are in a phase of regeneration. "Everyone needs new blood to improve," he said.

"Top Chinese firms no longer market themselves with low prices; they want to be known for service quality," Ji added. "Having these heavyweight partners will be helpful in that sense."

Recruiters said more moves by global partners to Chinese firms are in the pipeline. Han Kun, which hired three global firm partners in 2017, admits it is currently in active discussions with several.

"We are expecting more people to join us from international firms in the coming months," Chen said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

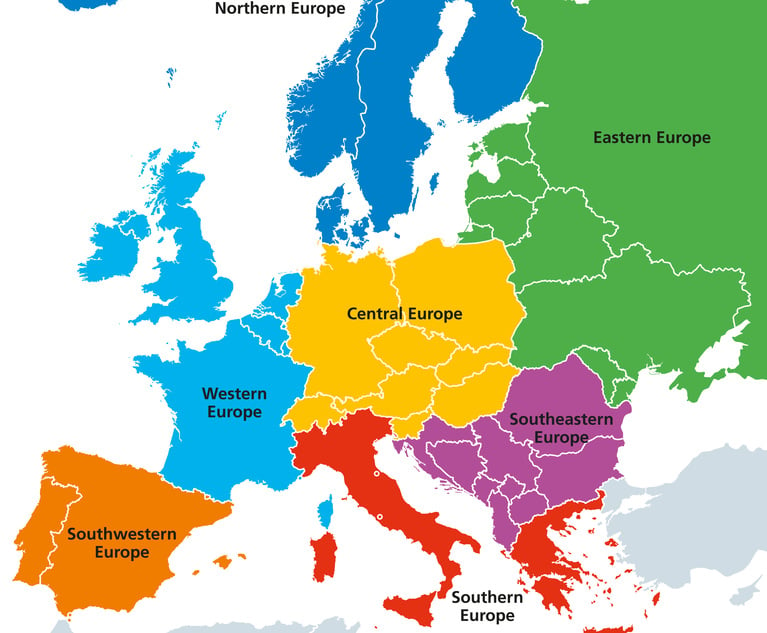

To Thrive in Central and Eastern Europe, Law Firms Need to 'Know the Rules of the Game'

7 minute read

GOP's Washington Trifecta Could Put Litigation Finance Industry Under Pressure

Trending Stories

- 1Gibson Dunn Sued By Crypto Client After Lateral Hire Causes Conflict of Interest

- 2Trump's Solicitor General Expected to 'Flip' Prelogar's Positions at Supreme Court

- 3Pharmacy Lawyers See Promise in NY Regulator's Curbs on PBM Industry

- 4Outgoing USPTO Director Kathi Vidal: ‘We All Want the Country to Be in a Better Place’

- 5Supreme Court Will Review Constitutionality Of FCC's Universal Service Fund

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250