Go Big or Go Niche: The Management Myth That Makes Little Sense in Law

Management consultants might not admit it, but commercial law is so profitable that you can do fairly well out of it even with very few differentiators

March 28, 2019 at 12:33 AM

5 minute read

Credit: AmySachar/Shutterstock

Credit: AmySachar/ShutterstockIt is the mantra management consultants love to espouse: Go big, go niche or go home.

So widespread is this logic – that success equals being either the biggest or the best – that it is repeated at almost every conference by almost every business leader in the country. You can easily imagine it preached by the likes of McKinsey & Company.

In some industries, it makes total sense to aspire to one strategy or the other. Retailers with high overheads either need to achieve sufficient scale in order sell cheaply in volume, or be niche enough to demand high-end fees.

But law firms around the world have accepted this reasoning to such an extent that those with neither international scale nor a specific area of practice expertise are often derided as institutions that will one day fall by the wayside.

Look at Slaughter and May, they say, and Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. They don't need to expand in order to succeed. And look at Latham & Watkins and Clifford Chance. They are hugely successful after expanding across the world.

The problem with this, of course, is that it is a self-selecting sample of the most successful firms operating the two extreme models. There is also a survivorship bias. For every success story of a targeted strategy like Slaughter and May, there is a less glamorous story of a firm being acquired or collapsing, like Ince & Co. And for every example of global growth like Clifford Chance, there are forgotten cases of failures like Coudert Brothers.

If scale was the single defining factor of a successful law firm business model, then surely Baker McKenzie, Dentons and CMS would be classed as the best institutions around. After all, they have the most lawyers and the most offices.

And if simply remaining small or with a narrow specialist focus effectively guaranteed riches, then the likes of BLM and Hill Dickinson would be among the most profitable, when in actual fact they have some of the lowest average profits per equity partner in the U.K. top 50.

In the legal world, the reality undermines the consultant's market logic. There are some firms that do not really benefit from scale and others where it makes little sense for them to limit their growth. And perhaps most importantly, there are plenty of successful medium-sized law firms that have neither a universal presence nor a niche strategy.

Ashurst, Simmons & Simmons and Stephenson Harwood are examples of these. All three are fairly big, but nothing like the size of the largest U.K.-based legal institutions. They are all pretty good in a variety of practice areas but may not excel at everything.

Conventional business logic would suggest that these firms are on their way out. And it is true that Ashurst has a storied history that once placed it as a competitor to the Magic Circle, something it would struggle to claim now.

However, all three firms rank above many larger competitors by revenue per lawyer and profit per lawyer, as they have done for many years.

If we divide up the top 200 law firms in the world into large, niche and mid-tier, the message becomes even clearer.

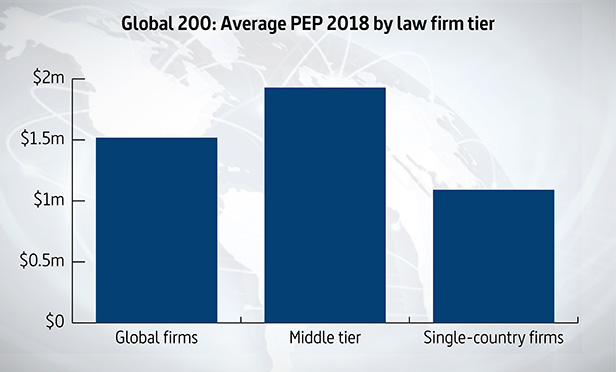

Let's say large firms are those with more than 2,000 lawyers operating across more than 10 countries, and niche firms are those in just one country with fewer than 500 lawyers. The firms in between – those with between 500 and 2,000 lawyers, operating across between two and 10 countries – have the highest average equity partner profits of all three groups, according to bespoke research by ALM Intelligence database Legal Compass.

Source: Legal Compass

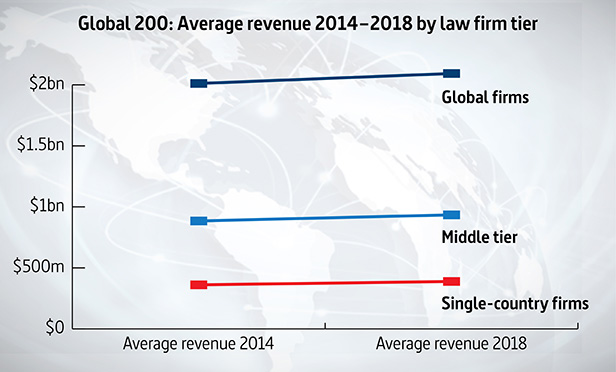

Source: Legal CompassAnd in growth terms, firms in that middle tier are expanding at a similar pace to those in both the global and niche tiers.

Source: Legal Compass

Source: Legal CompassThe truth is that commercial law is so profitable that you can do fairly well out of it even with very few differentiators. You need not be the biggest or the best and you can still enjoy a comfortable existence.

This may not fit with a management consultant message, because it would be strange to pay high fees only to be told to carry on regardless. Where would be the so-called added value in that?

In the late 1990s, Norton Rose brought in Bain & Co for some costly advice, a process that culminated in the firm attempting to be one of the handful of top global law firms in less than 10 years. Subsequent efforts to build up an international network proved more painful than most could have ever predicted.

Perhaps having a grand strategy just feels better, even when the merits of such a plan are highly debatable.

The head of one large international firm says: "Clients don't care if you have a large international network. What they care about is whether you are good and the offices are integrated."

He may well be right. But he'd never make it as a management consultant.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to asset-and-logo-licensing@alm.com. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Quiet Revolution: Private Equity’s Calculated Push Into Law Firms

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 2'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 3Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

- 4On the Move and After Hours: Meyner and Landis; Cooper Levenson; Ogletree Deakins; Saiber

- 5State Budget Proposal Includes More Money for Courts—for Now

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250