How International Turmoil Has Fuelled Growth at Global Firms

Clients have needed extra guidance to deal with the upheaval created by trade tension and geopolitical uncertainty.

September 24, 2019 at 05:30 AM

10 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The American Lawyer

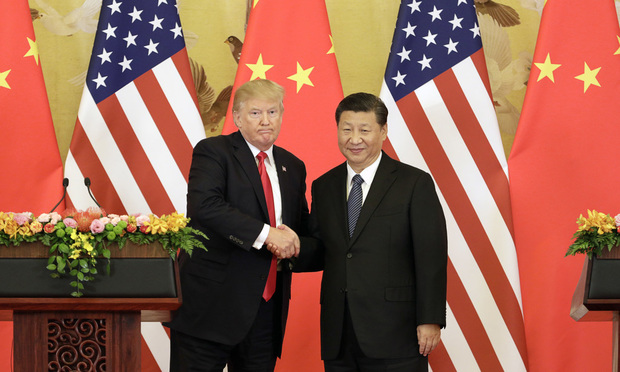

President Donald Trump, left, and Xi Jinping, China's president, shake hands during a news conference at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on Nov. 9, 2017. Credit: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

President Donald Trump, left, and Xi Jinping, China's president, shake hands during a news conference at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on Nov. 9, 2017. Credit: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

When it comes to international trade, bad headlines mean good business for some global law firms.

Since President Donald Trump took office and declared his intentions to get better trade terms from China and other U.S. trading partners, including Canada and Mexico, nothing has settled down for global companies or the firms that advise them.

Any lawyers who once thought the initial upheaval would subside have since learned to expect the unexpected. Yet global firms say they have profited in the last couple of years from clients' increased need for expert counsel to help them deal with it all.

Regulatory practices are especially strong of late and, as long as the economic downturn many firms anticipate doesn't become a deep global recession, they expect that growth to continue. In practices as wide-ranging as international trade policy, national security, antitrust and government contracts and investigations, firms are seeing a silver lining in the global turmoil.

"This has all been very good for law firm business, but maybe redirected the business a bit," says White & Case partner John Reiss, global head of the firm's mergers and acquisitions group. He says "volatility and uncertainty" are making some jurisdictions more attractive for investors, and others less so.

In less than three years in office, the Trump administration has overseen a steadily expanding thicket of thorny trade issues. Talks aimed at cutting the U.S. trade deficit with China had gone nowhere as summer wound down. Each time negotiations have broken off, Trump has imposed or threatened higher tariffs on more imports. China has retaliated by restricting imports of U.S. farm products and raising tariffs on U.S. goods, as well as devaluing the yuan, prompting the U.S. Treasury to designate it a "currency manipulator".

Foreign direct investment into the United States from China has plunged as a result of China's recent restrictions on capital outflows and heightened scrutiny by U.S. regulators that has disrupted or aborted deals. The EU also is tightening national security reviews of foreign investments, and tighter export controls and trade sanctions have placed new obstacles on trade and dealmaking.

In Europe, Brexit continues to cast a long shadow over business in the United Kingdom, which fell from first to sixth in foreign direct investment in the United States from Europe, according to U.S. government data. The U.S. has increased sanctions on Russia and Iran, and in Latin America sweeping U.S. sanctions continue against Venezuela, a major oil exporter.

Even on the North American continent, trade tensions between the United States and its neighbours have escalated at times, as the countries renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (now called the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement), which had been in place for 25 years. And an inverted yield curve on U.S. Treasury notes, long considered a sign of an impending recession, exacerbated financial market volatility in August.

Through it all, law firms capable of addressing clients' long list of concerns are benefiting, they say.

"It is not the ideal motivation, but we have seen a noticeable uptick in demand for services in the areas most affected by the current situation, and it also drives certain defensive and strategic dealmaking," says Jaime Trujillo, acting global chair of Baker McKenzie.

Tax, restructuring and compliance and investigations lawyers are in high demand at the moment, he says. In the firm's annual report released in late August, M&A, private equity and capital markets showed growth, with technology, media and telecommunications, healthcare, and energy, mining and infrastructure marked as the highest-growth industry sectors.

"Clients are more focused on understanding the implications and complexity. Even the less-sophisticated ones are demanding true expertise in sanctions, trade and CFIUS," Reiss says, referring to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, the interagency panel at the Treasury Department that reviews foreign investment in U.S. companies for national security risks.

Even deals with no U.S. component may still encounter U.S. regulatory issues in the current landscape, says Jeffrey Kochian, partner and head of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld's corporate practice in New York.

"Even if you are doing a deal entirely outside of the U.S., you may have U.S. regulatory issues, and we are fortunate to get those calls," Kochian says. "The same is true for internal U.S. transactions – we may need antitrust clearance in the EU for things of that nature."

Cross-border M&A goes M.I.A.

Signs of a global slowdown in mergers and acquisitions were apparent in the first half of 2019. Global M&A activity decreased 10% year over year in the first six months of the year, according to Bloomberg data. Megadeals were responsible for about half of the total value.

But cross-border M&A deals dropped 45% in that span, according to figures released in July by Refinitiv. And two-way completed foreign direct investment between the U.S. and China dropped a whopping 70% from its record level of $60 billion in 2016, according to data from Rhodium Group. That shift has been a major contributor to the overall decline.

"Deals that don't cross jurisdictions tend to be the deals that are getting done, whereas those that cross multiple jurisdictions are more challenging," Kochian says.

European M&A also fell because of a weaker economy, according to Refinitiv. Once-hot tax-inversion deals, in which U.S. companies domicile abroad, ceased after Trump's tax reform, and a strong U.S. dollar made U.S. companies more expensive for foreign companies to buy. Interest rate risks and volatility in the price of oil also played a role in damping down M&A activity, Kochian says. The United States has actually been a bright spot for M&A activity globally.

"Deals are still happening," Trujillo says, "but not for the reasons that would have been present two or three years ago." Rather, clients are making moves in preparation for changes they anticipate in the near future, he says.

Some Chinese investment that had been going to the United States is simply shifting to other places, including Latin America, Africa and within Asia itself. And a lot of Chinese investment is being plowed back into the country to build up its domestic consumer economy and regional infrastructure. Additionally, China's Belt and Road Initiative stretching from Asia to Europe and Africa is extending the country's global reach, says Julia Hayhoe, Baker McKenzie's chief strategy officer.

China's GDP growth is north of 6%, a "respectable" number, Hayhoe says. But while China now has more Fortune Global 500 companies than the United States (129 to 121), the vast majority of their revenue is domestic, meaning global firms need to have strong capabilities and relationships to succeed within China's borders, she says.

"Smaller international players are struggling," Hayhoe says. "You have to have a very strong practice on the ground and it has to be connected into the international capability. You can't just fly in and fly out."

U.S. trade conflicts with China also could have implications for future law firm expansion and recruitment abroad, says Nathan Peart, managing director of Major, Lindsey & Africa's associate practice group. He recently returned to New York after a long stint in Hong Kong.

After a period during which some U.S. firms worked to establish a foothold in China or tie-up with Chinese firms, more work is heading back to the mainland and Hong Kong-based firms, Peart says. And new hurdles for Chinese law students to obtain sponsored work visas from U.S. employers after graduation will mean fewer students can gain experience at U.S. firms before returning overseas, which could have long-term implications, several lawyers say.

"My sense is that the markets are going to end up being quite separate in terms of law firm business," Peart says. "If you are doing business in China, Chinese firms are dominating the market."

Answering the call

As global tension between free trade and protectionism rises, it's brought up a fundamental question that has entangled lawyers, says Steven Croley, a partner and co-leader of the CFIUS and U.S. national security practice at Latham & Watkins. How can the United States protect its national security while also remaining open to the foreign capital (and goods) that the country desires?

The search for answers has given clients new reasons to call their lawyers. "Regulatory programmes have gained in prominence and interest from clients in and outside the U.S.," says Les Carnegie, partner and co-leader of Latham's CFIUS and U.S. national security practice.

In particular, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act, which Congress enacted last year to overhaul the national security review process at CFIUS to include even minority stakes in tech startups, has created more work for specialists, as have new tariffs and heightened enforcement of export/import controls and sanctions, according to Greg Spak, head of White & Case's international trade group.

Spak says there has even been "a boom in basic customs law, which became less interesting and active when duties didn't matter anymore, but now it is booming again". Moreover, like bankruptcy, trade regulatory work is countercyclical, he notes.

Advisory work is also up. "It was a low simmer, but that is starting to turn into a low boil," because general counsel aren't always deeply familiar with trade rules, Spak says.

Sanctions advice is also in demand. "There has been a virtual tsunami of demand for high-calibre sanctions advice and counselling, given the importance of getting sanctions compliance right and the rise in enforcement," Carnegie says.

The new trade environment is also creating work for lobbyists representing companies before government agencies that are drafting new rules. For example, three lawyers from Sidley Austin with white-collar and export sanctions experience recently registered to lobby for the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei Technologies, which has been charged with violating U.S. sanctions.

Most lawyers interviewed for this article have short-term confidence in their own firms and practices, but they also believe escalating tensions with China, financial market volatility, signs of a global economic slowdown and the general atmosphere of uncertainty are likely to hamper some firms' finances in the coming months. And they share a concern that instability could take a lasting toll on the world's economy, which wouldn't be good for anyone, law firms included.

"The potential for major disruption is there and we are all expecting an economic slowdown, but the magnitude of that slowdown could turn into something more serious if our world leaders do not play their cards right," Trujillo says. "If the planets align in a certain way, we have to brace ourselves."

Stephen Kho, an international trade policy and dispute resolution partner who joined Akin Gump after nine years at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, where he was associate general counsel and acting chief counsel on China enforcement, acknowledges that uncertainty can drive activity at firms.

But Kho points out: "These are short-term problems that don't lead to long-term growth or long-term deals. This situation is not ideal. Stability and predictability are good for everyone, but that is not what we have right now."

Email: [email protected]

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

X Ordered to Release Data by German Court Amid Election Interference Concerns

Compliance With the EU's AI Act Lags Behind as First Provisions Take Effect

Quinn Emanuel's Hamburg Managing Partner and Four-Lawyer Team Jump to Willkie Farr

Trump ICC Sanctions Condemned as ‘Brazen Attack’ on International Law

Trending Stories

- 1Parties’ Reservation of Rights Defeats Attempt to Enforce Settlement in Principle

- 2ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 3States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 4Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 5Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250