From The Litigation Daily:

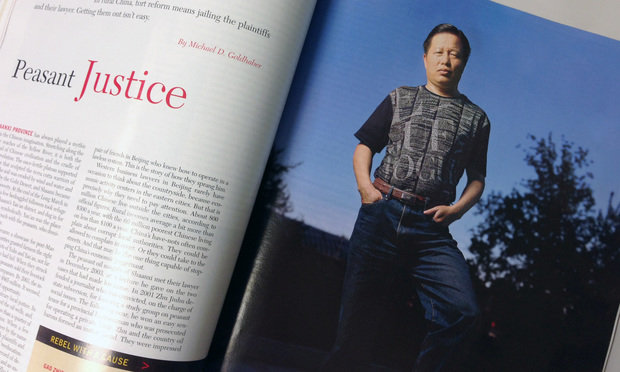

In November 2005, The American Lawyer ran a full-page photo of the larger-than-life Beijing human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, posing defiantly with his hands tucked into his jeans, exuding more dignity in his knock-off t-shirt than a thick magazine full of attorneys in business suits. Before the issue could even hit your mailbox, Gao’s 20-lawyer law firm had lost its license, thanks to Gao’s full-throated defense of the Falun Gong. Gao was soon arrested.

The caption for the accompanying story, “Peasant Justice”—about Gao’s brave defense of another rights advocate—noted that tort reform in China means jailing the lawyers. The punchline: “Getting them out isn’t easy.” We didn’t know the half of it.

In honor of this month’s Chinese communist party plenum on “socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics,” let’s review Gao’s lived experience of the rule of law as currently expressed in China. This account draws on reports by Freedom Now and other nonprofits. The Global Lawyer invites the American bar to join its voice to President Obama’s in urging Xi Jinping to let Gao leave the country before the U.S.-China presidential summit on Nov. 12.

Gao was already under pressure when I met him at a Beijing bookstore in August 2005. He had obstinately insisted on defending China’s most despised: the Falun Gong (banned by the state as a “cult”), a Bible-pushing Christian pastor, impoverished urbanites evicted for the Olympics, and powerless peasants pillaged by local officials. Weeks before we met, a client had been stung by secret police posing as journalists, so he was wary. After changing our meeting place twice, Gao tapped me on the shoulder as I browsed.

Gao spoke with disdain of China’s controlled judiciary. He called on both local and Western law firms to rally around persecuted lawyers. When I asked where he found his courage, Gao spoke of his mother, a Buddhist so devout that she’d gather the bones scattered by grave robbers to give them a proper burial. As an adult, Gao was inspired by a Falun Gong client to find his own faith in Christianity. He understood the danger of his game, yet he saw no choice. “Our giving up of our effort in human rights protection,” he wrote in a stiffly-translated essay, “will be our encouragement of illegal behavior and the giving up of our conscience.”

Driven by a sense of mission, Gao responded to confrontation in kind. In December 2005—the month after he was profiled in The American Lawyer and lost his law license—Gao publicly renounced his Communist membership and called for an end to Falun Gong persecution. He was put under 24 hour surveillance. From Aug. 15 to Sept. 21, 2006, he was secretly detained. According to his own account, Gao was forced to sit motionless in an iron chair for hundreds of hours under bright lights. He temporarily confessed to “inciting subversion” in response to threats against his children. “I decided I could not haggle about my children’s future,” he wrote.

In the ensuing months his family was harassed anyway—his wife punched on the street, his 13-year-old daughter dragged into a car. The police (likely the state security or protection bureau) even tried to pick up his two-year-old son from preschool. In Dec. 2006, after a trial of less than a day conducted without notice to his legal team, Beijing’s First Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Gao to a three-year prison term, which was supposedly suspended in favor of five years probation.

In practice, this meant five years alternating between oppressive house arrest and tortuous disappearances, followed by three years of obscene solitary confinement. For many days of those eight years, Ivan Denisovich had it easy by comparison.

House arrest entailed six to eight policemen living in the Gao family home. The police would not let them dim the lights while they slept or close the door when they defecated. Gao was not allowed outside. The police at first drove his daughter Grace to school. Then they blocked her from getting an education. For Gao’s wife Geng He, that was the last straw. With the help of Falun Gong sympathizers, in March 2009 she and the children slipped away from their minders and traversed a perilous route over the Burmese border. They soon won asylum from the United States, where Grace is now enrolled in college.

Gao himself was periodically hooded and kidnapped in the dead of night for special treatment in the basement of a police station. He would then infuriate his captors by relating his experience to the world, breaking a tacit code and, worse, showing an unbroken spirit. In September 2007 he disappeared for 50 days. His keepers, he said, had shocked his genitals with an electric baton and pierced them with toothpicks to extract a new confession. In February 2009 he disappeared for 14 months. At various times, Gao said, he had been hooded, bound with belts, pistol-whipped, threatened with death, and told his children were having nervous breakdowns.

Only three weeks after Gao resurfaced, the Chinese authorities tired of being trifled with. In April 2010 he disappeared for 20 months to solitary confinement at an army base in a cold northern province with no heat, clad only in summer cotton. When asked about Gao’s whereabouts by a New York Times reporter, a Foreign Ministry spokesperson replied glibly that he was “where he should be.” Finally, in Dec. 2010, China acknowledged Gao’s existence long enough to withdraw his probation and ship him for three years to Shaya County Prison, in the far western province of Xinjiang.

There the solitude of Gao’s confinement deepened beyond imagining. He was held in a 70 square-foot cell lit around the clock by a five-watt bulb. There was no other light, heat or ventilation, no reading or writing materials, no exercise, no human interaction of any kind beyond being handed a piece of bread and a bowl of watery cabbage each day. His guards were put under strict orders not to speak with him.

Gao was released to house arrest at the conclusion of his sentence on Aug. 7, 2014. The tall man who had projected vigor in our portrait was now a 137-pound skeleton. For a time he couldn’t walk without being propped up, and when he opened his mouth to speak, his mouth just shook. Much of what he said was unintelligible. The first time he was able to speak this summer, Gao told his wife by phone to take their son Peter to church, because faith is what kept him going. Peter, now 11, cannot remember his father’s voice. He asked why Gao had done things that kept the family apart. I love you, Gao replied, but I must also love others.

Geng He said in an interview with The American Lawyer that her husband is making strides, and that “his heart still longs for justice.” She thanked the American Board of Trial Advocates and American Bar Association for giving Gao awards in 2007 and 2010. She singled out Jared Genser of the nonprofit Freedom Now, who has made a career of rescuing headstrong dissidents, for making sure Gao wasn’t forgotten before or after the award ceremonies.

“Gao Zhisheng’s colleagues [in China] mostly kept silent through the entire torture and persecution,” Geng said through an interpreter. “We want to express gratitude toward American legal society. Without the attention of American government officials and legal human rights organizations, Gao Zhisheng might have died.”

It will take the continued attention of U.S. lawyers to win Gao’s release from the world’s largest prison, which for Gao and others like him, is China itself. It will take the renewed attention of Chinese lawyers to slowly transform their society, and make that insulting metaphor inapt.

But in a nation resolved to break their bodies, can human rights defenders maintain the spirit to carry on? The answer is an emphatic yes. Next week’s column will chronicle the surprising resurgence of human rights in the Chinese legal profession.

This article originally appeared on The Global Lawyer, a regular column by The American Lawyer senior international correspondent Michael D. Goldhaber.