Inside the Big Four's legal market playbook: the PwC-Fragomen alliance unpacked

The alliance suggests the Big Four's expansion in the legal market is speeding up. It also provides insight into what the Big Four's strategy in other areas of the industry might look like.

October 03, 2018 at 12:00 AM

9 minute read

Last Monday (24 September), PwC and US immigration law firm Fragomen announced a strategic alliance. In a joint statement, the firms said the alliance would see the two firms collaborate and jointly market their immigration services. It also stated that their new arrangement would give them the ability to come together to provide "integrated services" to their clients.

The deal is far more consequential than the dry press release suggests. The alliance will speed up the Big Four's already quick expansion into the immigration space. It will also serve as a test case for partnerships in other areas of the legal industry.

Law firms should also look at this announcement in a wider setting. Fragomen's decision to enter into this alliance is important to unpack. The firm didn't have to join forces with PwC, a 10,000-pound gorilla that will almost certainly dominate the "alliance". Understanding the logic behind Fragomen's choice could be useful to other firms. The obstacles Fragomen faced before making this decision and the options it had to address those obstacles are likely similar to those that other law firms will face in the coming years, as the Big Four continue to expand. Below is an analysis looking at each of these issues.

The immigration market

For law firms with large immigration practices, Monday's announcement was likely to have come as not much of a surprise. The Big Four have been expanding into the immigration space for nearly a decade. That expansion has been speeding up in recent years. In June of this year, for example, Deloitte acquired the non-US offices of Berry Appleman & Leiden (BAL), another leader in the immigration space, and signed a partnership with the firm's US practice. In this context, the alliance between PwC and Fragomen could be seen as yet another example of the Big Four's growing presence in the immigration space. However, such a view is misguided because it understates the deal's importance. This announcement is not just another data point on the same trend line.

Fragomen is the largest provider of immigration-related legal services in the world by some distance. The firm generated revenues of $577m during 2017 from 553 lawyers, who are all focused, in one form or another, on immigration-related legal services. In contrast, BAL is about a fifth of the size, with 109 lawyers.

More important than Fragomen's size, is its reputation. The firm is widely regarded for its expertise in immigration-related law. Fragomen has long held the top spot on Chambers & Partners' global list of highly regarded immigration firms. The second and third spots, interestingly, are held by PwC and BAL. Now that BAL has joined forces with Deloitte and PwC has joined forces with Fragomen, the Big Four will hold the top two spots exclusively.

➤➤ Effective legal collaboration strategies and innovative partnerships will be explored on day one of LegalWeek CONNECT, taking place on 28-29 November at County Hall, London SE1. Click here for more information

The Big Four's presence at the top of the immigration market will put pressure on other firms. Baker McKenzie, Mayer Brown and Morgan Lewis & Bockius all have relatively large immigration practices. Competing with the Big Four will not be easy. PwC's geographic coverage, a key competitive advantage in immigration law, is unrivalled. Its global immigration practice, for example, covers 170 countries. The Big Four's size will also be an asset. It will allow them to invest in new technologies and new processes to improve service quality and reduce costs. Their strong offerings in consulting and tax also will be useful – they act as lead generators for immigration legal practices. Some large law firms will, no doubt, find ways to compete with the Big Four. But others will not. It would not be surprising to see one or more large law firms spin off their immigration practice to a Big Four player. EY, which has a presence in the immigration space but has not signed a deal with a large law firm yet, would be a likely home for such a spinoff.

Even if spinoffs do not happen, the writing is on the wall. The Big Four are now the elephants in this (admittedly small) corner of the legal market.

Beyond immigration – a view of the Big Four's legal market playbook

A first glance, Fragomen's decision to enter into an alliance with PwC may seem odd. The firm has grown substantially in the past decade. At nearly $2m dollars in average profit per equity partner, the firm is also fairly profitable. Why would such a successful law firm enter into an alliance with a much larger Big Four player that is likely to dominate the partnership? The answer is that Fragomen's success in recent years is not quite as strong as it would initially appear.

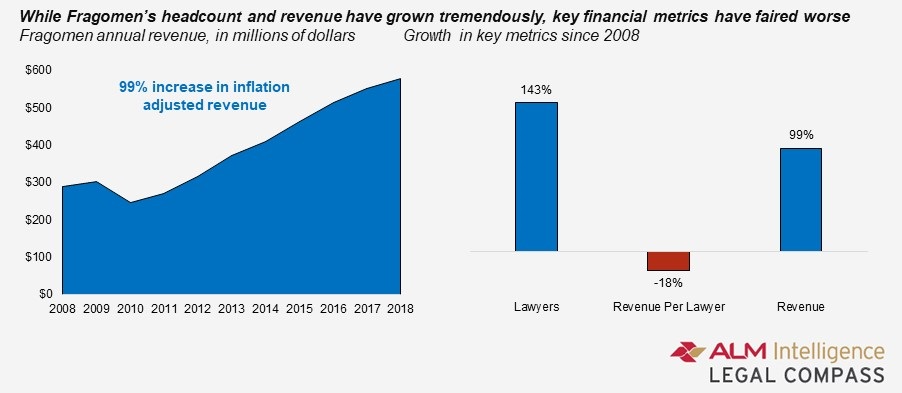

It is true that Fragomen has grown substantially in the past decade. In fact, the firm has nearly doubled since 2008. This makes Fragomen one of the fastest-growing firms in the legal market. That growth, however, is almost entirely due to increases in headcount. The firm has seen headcount, in lawyers, increase by 143% since 2008. In contrast, revenue per lawyer (RPL) has decreased, on an inflation-adjusted basis, by 18% during the same period (see below). Decreases in RPL are often linked to reductions in hourly rates. This suggests the firm's pricing power has shrunk in recent years. Given the mood of corporate clients and the continued encroachment of the Big Four on Fragomen's market, a reduction in pricing power is not surprising.

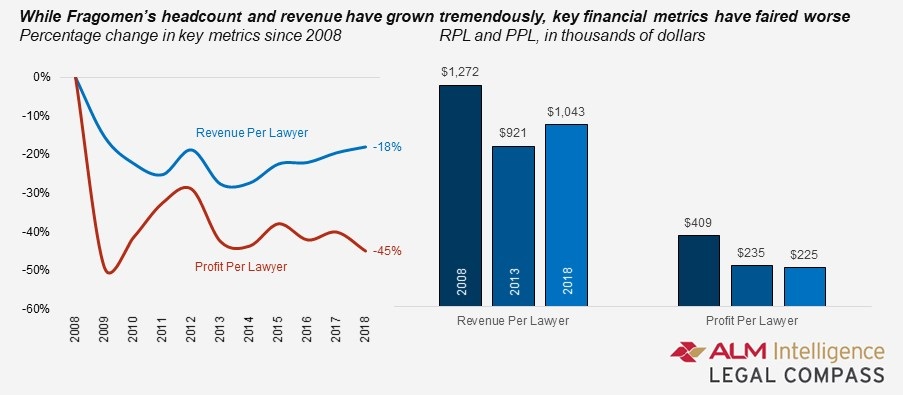

A deep look at Fragomen's financials reveals more concerns. Profit per lawyer (PPL) shrunk significantly after the downturn and has not recovered since. Even more concerning is the fact that PPL has continued to drift downward during the past several years (see below). Again, this is not surprising. Given the market conditions Fragomen has faced in recent years – price-sensitive clients and increasing competition from larger firms – reductions in profits are exactly what would be expected.

Fragomen had few good options. Deloitte's acquisition of BAL in June was a clear sign that the Big Four's expansion in the immigration space was not going to abate. The firm's lagging financials suggested a 'go it alone' strategy was unlikely to work. Partnering with PwC may have been a difficult choice, but it was clearly the firm's best option.

The Fragomen story should not be seen as an isolated case. A similar series of events could play out elsewhere in the legal market. It could look something like this:

- Market entry: The Big Four expand organically into a new area of the legal market.

- Expansion: The Big Four leverage their brands and existing line of services in consulting and tax to gain market share among corporate clients.

- Weaken competitors: Increased competition by the Big Four weakens legacy service providers, putting pressure on their financial models.

- Acquisitions: The Big Four act as white knights to legacy providers, partnering with them in "alliances" or acquiring them via "mergers".

Such a storyline could play out in a wide range of areas in the legal market. The alternative service provider space is, arguably, the most likely. These firms focus on service lines that would find a natural home inside a Big Four firm. Services such as contract management, e-discovery, intellectual property (IP) management and regulatory-related services would fit well with the Big Four's existing strengths. EY's acquisition of Riverview, last month, is evidence the Big Four are targeting this space already.

How this might play out in the law firm market is less clear. The Big Four, it is argued, will steer clear of areas where there is a significant amount of litigation work. The reason or this is that the Big Four's business model is premised on developing strong ties with corporate clients – litigation creates enemies. This makes expansion into areas like labour and employment tricky. Acquiring a labour and employment firm would require taking on a fair amount of litigation work. Acquiring an IP firm would create similar problems.

The solution to this dilemma may be acquisitions that are paired with spin-offs. The Big Four could acquire an IP firm and then spin off the litigation work into its own independent law firm. This could leave both sides of an IP firm better off. Litigation practices are often more profitable. The non-litigation practices, on the other hand, require scale and continued investment in technology and process improvement to be competitive. Splitting these two businesses makes sense. Placing the volume-oriented business inside a Big Four firm will make it more competitive. Letting the more profitable litigation partners go their own way would allow them to: (1) increase their profitably by getting rid of the lower-value non-litigation work; and (2) avoid conflicts created by the non-litigation work.

Spin-offs of the sort described above would work in more areas of the legal market than most law firms are willing to admit. Labour and employment firms are an obvious candidate. Regulatory practices could also be split, as could corporate practices. There is no reason why contract work, low-value M&A work and other low- to mid-value corporate work cannot be performed inside a Big Four firm.

What is most interesting about this scenario – where litigation practices are split from non-litigation practices – is that it could come about in a few ways. Spin-offs are just one possibility. It could also happen more organically through the lateral hiring markets. Partners in non-litigation practices could decide they would be more competitive inside a Big Four firm. Partners in litigation practices, on the other hand, could decide they would be more competitive (and more highly paid) in a litigation boutique. There is some evidence this kind of self-sorting is already happening.

This scenario is not inevitable of course. There are good reasons why litigation and non-litigation practices are currently inside the same firms. That said, this scenario seems possible. Law firm leaders should be imagining such scenarios. Fragomen made the decision to join forces with PwC before they had to. Other firms would be wise to see the writing on the wall and act before urgency sets in.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

4 minute read

KPMG's Bid To Practice Law in US On Hold As Arizona Court Exercises Caution

Trending Stories

- 1Public Notices/Calendars

- 2Wednesday Newspaper

- 3Decision of the Day: Qui Tam Relators Do Not Plausibly Claim Firm Avoided Tax Obligations Through Visa Applications, Circuit Finds

- 4Judicial Ethics Opinion 24-116

- 5Big Law Firms Sheppard Mullin, Morgan Lewis and Baker Botts Add Partners in Houston

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250