Government Data Collection Efforts Yield Cybersecurity Questions

The breach of India's national ID database Aadhaar raises concerns as to whether governments are equipped to deal appropriately with today's cybersecurity landscape.

January 16, 2018 at 12:56 PM

8 minute read

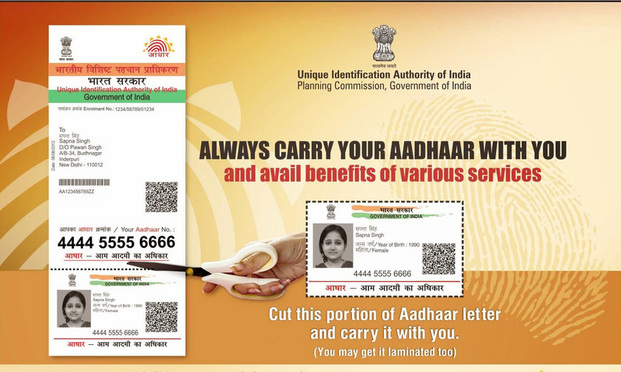

India's Aadhaar identification card.

India's Aadhaar identification card.

In 2009, Indian officials first pitched the idea for Aadhaar, an online national identification system containing personal and biometric information. It was touted as a “turbocharged version of the Social Security number,” a database that could act as a digital cure for identity fraud and make identity verification an easier and more streamlined process. In the last eight years of its operation, Aadhaar has been both widely expanded to integrate with tons of government and online services, and widely criticized as a privacy risk for Indian nationals if it were to be hacked.

As feared, earlier this month Indian newspaper The Tribune announced that it had successfully breached the controversial national database, exposing data for upward of 1.2 billion Indian nationals. The newspaper reportedly paid a hacker the equivalent of $8 to create a login that would allow reporters at the Tribune to access information for all registered members of the database. A second news outlet, The Quint, found another vulnerability in the system allowing existing administrators to offer any person new administrator credentials to the database.

And Indian officials are not alone. Governments' efforts to bring their resources into the digital era, particularly with databases of consumer information, are increasingly running into concerns about cybersecurity.

Craig A. Newman, partner with Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler, noted that storing collections of personal data lacking in basic data security protocols is not a particularly viable posture in today's cybersecurity landscape. “A database like Aadhaar is a virtual stockpile of confidential information including photos, fingerprints and retina scans. Whenever that type of data is aggregated in a single place, implementing robust and layered data security safeguards is a must.”

The private sector has learned this lesson the hard way over the last few years. 2017 alone saw data breaches at many of the most well-resourced companies in the United States, companies like PayPal, Equifax and Yahoo. The scope of those breaches seems to have grown as well, with Equifax's breach affecting over 145 million customers, and Yahoo's breach revealed to have affected all 3 billion of their account holders.

“The government is no different,” Newman said. “It doesn't matter if it's public or private sector—hackers follow the money and data,” he later added.

Indeed, U.S. government agencies seem to have become just as fruitful a target for hackers as private corporations. Last year also saw major hacks at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Office of Personnel Management (OPM), both agencies that may not necessarily inspire much concern about cybersecurity risk at face value. 2016 also saw a reported 30,899 cyber incidents and 16 major incidents at federal agencies that compromised data.

Even when hackers don't intentionally target agencies, human error issues can put private consumer or employee data at risk of exposure. In early January, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) confirmed that a former employee retained access to nearly 240,000 current and former employees' personal information.

Although consumers affected by government data breaches theoretically have the ability to seek legal recourse, U.S. courts so far haven't shown much interest in validating standing for lawsuits.

“It's been tough for individuals to sue the government when their data is breached. Similar to the private sector, these individuals have had difficulty establishing that they have the legal standing—or in other words, have suffered concrete harm or injury—sufficient to pursue a lawsuit. The class actions filed against the Office of Personnel Management were dismissed on precisely these grounds,” Newman noted.

Andrew Grotto, an international security fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University and former senior director of cybersecurity policy at the White House, noted that both resource allocation and organizational policy shape the likelihood of data exposure at U.S. government agencies, something that varies widely across agencies.

“I wouldn't lump not even all agencies within the U.S. federal government together. There are some that are better than others. Some of it is resources, but a lot of it is management culture. But resources really do matter, especially when you get into state and local governments,” Grotto said.

Grotto was part of a group of nine former national security and technology officials who filed an amicus brief supporting a lawsuit concerning privacy concerns over the U.S. Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity's proposed effort to consolidate U.S. voter information into a national database. The group wrote that the proposed database posed a “grave vulnerability” to hacking by foreign actors.

President Donald Trump announced last week via Twitter that he would disband the commission, and Department of Justice operatives this week stated their intent to destroy, rather than archive or transfer, the voter data collected by the commission to date.

Grotto voiced concern about the voter information database because he felt that the risk of cyberattack would likely outgun even the best U.S. cybersecurity resources. “The risk is high. Even with world-class protections around it, there would be a lot of foreign government and criminal actors and others who would love to get their hands on this data,” he said.

It's not always the case that aggregating government data poses too great a cybersecurity risk. Other government data centralization projects do propose some important benefits to agencies and residents. Data aggregation can help with agency collaboration and efficiency, research, and a whole host of other core government functions. It can even be a way to bolster cybersecurity, as with DHS's EINSTEIN program that detects potential threats in agency web traffic.

With any large government data centralization project, Grotto said, it all comes down to managing cyber risk. “Managing cyber risk is just about evaluating the costs, benefits and the risks,” he noted.

Failure to appropriately evaluate those risks, however, can expose a great deal of private information. Grotto noted that U.S. privacy law shapes data security conversations slightly differently than other parts of the world. While European models tend to uphold privacy as a fundamental right, “In the U.S., we have a very pragmatic balancing type test where we balance interests. It's not a fundamental right in the same way,” Grotto explained.

Other countries are still trying to shore up their stance on privacy in ways that could affect data consolidation and retention. India's Supreme Court has taken up questions about Aadhaar's potential privacy infringements even prior to the breach. The court heard arguments last July about whether privacy is a fundamental right of Indian citizens and whether use of the Aadhaar database poses any threat to that right.

The upcoming implementation date for the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) could force greater global alignment of privacy and cybersecurity policies, which may raise the bar for cybersecurity risks assessments across governments internationally. The regulation applies to any organizations doing business in European Union countries and carries a stiff penalty for noncompliance. Though GDPR is unlikely to target government agencies specifically, it could carry over into broader policy debates.

“I think one way we can see a change here is either through litigation in the European Union, companies being targeted for enforcement action in EU data breaches or companies, that sort of having an impact on the policy debate here,” Grotto noted.

Even if the GDPR doesn't promote these standards among government agencies and their data collection efforts, Grotto thinks that U.S. federal government agencies have made great strides in the way they evaluate cybersecurity risk and believes that they're likely to continue to do so. “I'm actually pretty optimistic that that thrust carried over from the last administration,” he said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 111th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 2Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 3'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 4Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

- 5On the Move and After Hours: Meyner and Landis; Cooper Levenson; Ogletree Deakins; Saiber

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250