A Cambridge Analytica Whistleblower's Challenge to Social Media Collection

A veteran of data collection for political campaigns and social media, Brittany Kaiser says technologies like smart contracts can help build a framework for personal data as personal property.

April 19, 2018 at 02:21 PM

5 minute read

The Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal is redefining how people view and interact with social media, but it's also spotlighting the legal framework around data privacy in the U.S. and how consumers can change it.

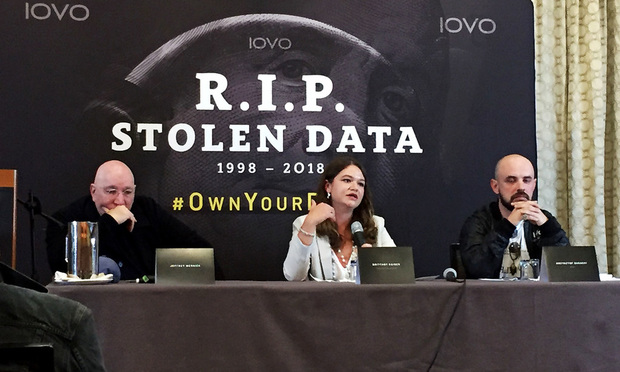

Speaking at an April 18 press conference in New York, former Cambridge Analytica business development director Brittany Kaiser joined a panel in proposing that internet users declare their data personal property, and utilize blockchain—the technology underlying Bitcoin—as a means for collectively pursuing a legal framework. And the pursuit, in her view, could prove lucrative.

Companies like Google parent Alphabet and Facebook are among “the world's most powerful” said Kaiser, who has been coined by news outlets a “whistleblower” in Cambridge Analytica's data practices. “All their value assets are based off the personal data of individuals. The value of the platform is that it continues to collect data on all of us on a day-to-day basis.”

Kaiser, who holds an LLM and specializes in international law, noted that many look to European Union data laws—which require EU citizens to “opt in” to have data collected, as opposed to the U.S.' “opt out” model—as a template for change. “But those European laws don't go far enough,” she said. “It still doesn't give you transparency on all the types of data being collected on you.”

Part of the reason is that data collected by groups like Facebook, as in the case with Cambridge Analytica, are shared with third parties, which then can use the information for their own purposes. And while U.S. users can opt out of sharing, the ability isn't always made obvious.

“Not many people know that there's an option to opt out,” Kaiser said. “You have to look for yourself, and it's not easy.”

What's more, while a user can opt to have their data deleted, Kaiser noted that such a process is difficult if one has been using a social media platform for 10-plus years. “You have to have quite a bit of money and very good lawyers to win some of those cases to remove your data after it's been collected and been made available to others.”

Fellow panelist Krzysztof Gagacki, founder of data management company IOVO, agreed. “Right now, we have the technology that can support the entire change of the data economic priority that is ongoing,” he explained.

Gagacki posited that legal issues surrounding data stem from the inception of the internet. “[S]ince it was created in a spontaneous way, there were no regulations dedicated to data ownership. That's why all the companies making their presence on the internet, they all basically make their revenues out of monetizing our data.”

“If we don't stop it now, then the future generation, they will have no rights, no knowledge about their digital property, which is crucial,” Gagacki added.

However, data literacy isn't the average person's strong suit. As Kaiser, who was recently named an advisory board member at IOVO, explained, “There's a very low amount of data literacy among individuals. Most people don't understand what it means when they click yes on terms and conditions.”

And such clicking has been going on for over a decade. Kaiser noted that she was working with data collection as far back as the 2007 presidential campaign for Barack Obama. Further, she said that the U.S. is far from the only country that collects data for political operations, set apart only in that there's “a plethora of data that is legal for you to purchase or license.”

“For many years, I never questioned it. This is the way the political system works, the advertising industry, every single industry in the business of digital communication, that's the way it works.”

In Kaiser's view, however, free access to platforms like Facebook in exchange for consumer data isn't “a good transfer of value.” She cited incentivizing people with payments to provide their data for specific uses as an alternative, with platforms like Facebook serving as the marketplace.

Panelist Jeffrey Wernick, a private investor who has worked with companies like Uber and Bitcoin, thinks that collective bargaining could make strong cases. To draw a formidably-sized group, he explained that digitized smart contracts, built on blockchain, could aggregate “the right to represent” people.

“It's almost like a class action lawsuit. … That way you extract a lot more value from it,” he said. “We just have to figure out how to organize ourselves. The blockchain is the ideal way to do it.”

“Given the fact that property rights are not defined [with data], the market cannot find a solution if there is no ownership claim,” he added. “Once we establish the concept that it is our property, organizations will figure out” how to make value propositions, which will “drive us to get the most value out of what we produce.”

However, with the present way many internet companies generate revenue, such a change might be difficult to enact. Kaiser said she started a campaign for Facebook to acknowledge personal data as property by April 30. In talking with Facebook leaders about the idea, however, she said some were more open-minded than others about the idea. She noted she was “taken aback and disappointed” at Facebook chief operating officer Cheryl Sandberg's statements about people having to provide data if they want Facebook for free.

“To me that sounds like a threat. To use your property or pay? I don't know about that,” she added.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 15th Circuit Considers Challenge to Louisiana's Ten Commandments Law

- 2Crocs Accused of Padding Revenue With Channel-Stuffing HEYDUDE Shoes

- 3E-discovery Practitioners Are Racing to Adapt to Social Media’s Evolving Landscape

- 4The Law Firm Disrupted: For Office Policies, Big Law Has Its Ear to the Market, Not to Trump

- 5FTC Finalizes Child Online Privacy Rule Updates, But Ferguson Eyes Further Changes

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250