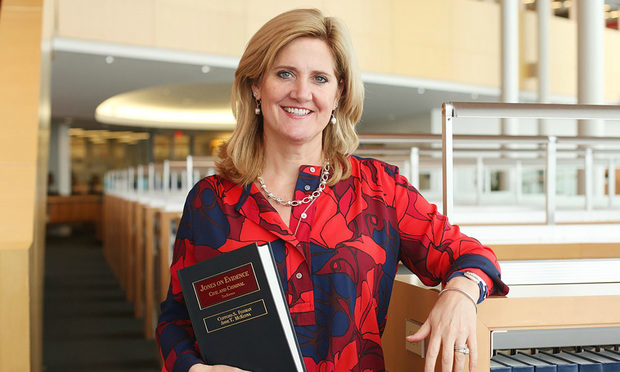

Q&A: Penn State Prof. Anne Toomey McKenna on Tackling the Evolving Nature of Cyber Law

The newly appointed Penn State professor sees a lot of room for questions in the evolving cyber law landscape, but so far there are few answers.

June 04, 2018 at 02:05 PM

8 minute read

As a law student, Anne Toomey McKenna worked as a research assistant for a professor who happened to be working on a treatise on wiretapping. McKenna thought she was headed for a career as a civil litigator and took the opportunity as kind of a one-off thought exercise, something that was unlikely to shape much of her career. Quickly, she realized she was wrong. McKenna found the knowledge base she'd developed while working on this system was a far bigger question for the organizations she was working with than she'd expected. Questions about phone call retention quickly evolved into data retention, and before she knew it, she was a cyber law expert. “If you think back to the 1990s, there was really a sea change about how business was run. For lawyers, the fact that everything went to electronic record radically changed law and evidence. These electronic evidence issues kept becoming more and more a part of my practice,” she said. McKenna recently joined Penn State's Dickinson Law and Penn State Institute for CyberScience as a distinguished scholar of cyber law and policy and professor in practice. She'll be heading up interdisciplinary research and learning with students looking at the cyber and data privacy space. Legaltech News recently caught up with McKenna for a Q&A: Legaltech News: How do you think recent technological transformations have translated into law school training? Anne Toomey McKenna: When people graduated from law school in 2010, they could get away with just taking the basic law school classes like civil procedure and common law. You didn't have to have a component of, "How did this change in terms of privacy? How does this change now that everything is online?" Now, if a student graduated and they just had evidence without exposure to electronically searchable information and ESI, they're not prepared to practice law today. It's almost a disservice. That's what really exciting what's really exciting about [Penn State's] Institute for Cyberscience and Dickinson [Law School]. Their focus is that we're preparing for this from the development of technology. They're doing so many cool things with internet of things; they're doing so many cool things with virtual reality and augmented reality. It's so neat to be someone large enough where all the engineers and the software people want to work with lawyers, and they want to do it right. You don't see that many places, maybe because they don't have a law school, but maybe because they're just busy engineering. Do you get the sense that engineering will continue to work faster than lawyers, or that engineers and lawyers will start to work a little more closely in the future? In U.S. law, we tend to be more reactionary to technological development, but I think what's changing that is the EU. With this [General Data Protection Regulation], everybody who wants to do business on a global scale that in any way touches Europeans is required to come into compliance. Have you noticed that every single app is sending you privacy notices? Isn't it so annoying? But at the same time it's so good, because they're trying to be proactive. In the U.S., we tend to regulate in a technology-specific way, meaning that like, cellphones come out and then we create some new legislation, so again, a reactionary response. But with GDPR, by treating data just as data that requires protection in and of itself regardless of platform, it's not technology-specific, it's privacy-specific, data protection specifically. I think that the law, particularly in the U.S., we have just been responding and trying to keep abreast of things. Think of how behind the Supreme Court is in addressing technology. In United States v. Jones, they were just trying to decide GPS tracking, and we're so beyond that with things like IoT. All of our devices are tracking us at all times, communicating with each other. That's one of the cool things about cyber law, is keeping abreast of the technology. We're moving towards U.S. lawyers in particular necessarily being required to understand global approaches to this from a legal standpoint. Any client that wants to have a presence—the positive side of GDPR is that U.S. legislation is going to file on top of that, because our businesses have to comply with it, particularly larger businesses. The differences are also so fascinating in the U.S. about the way we treat data. Medical data—that was HIPAA. Everyone in the legal space was familiar with HIPAA, but they weren't familiar with financial sector law, because it wasn't their space. Now all this information is being defined as personally identifying information, and instead of siloing data as we do in the U.S., it's really much more comprehensive in scope about data itself as opposed to breaking into medical versus financial. What kind of technical background do you think law students need at this point to be competent attorneys? I think that's critical. I think law students should be educated hand-and-hand with information technology students. When I was visiting at Penn State Law earlier this year, I worked with [Information Services and Technology] faculty, and we did a cyber hack simulation where we did a phishing email. We showed the IST students and my law students how a hack goes down, what it looks like from a technical standpoint. We sat there and typed in the breach, showed how the breach occurred, showed how we mimicked and obtained all the passwords for the system. Then what laws come into play? That's how we have to educate people, or we're just not going to develop and educate lawyers who are prepared for what the legal market and the business world and individuals need right now. Lawyers can no longer be just like, " I specialize in law and cyber." Everyone has to have engaged knowledge. It seems like a lot of these issues have broad implications outside of business compliance, in cases like public security and surveillance. How do some of these legal frameworks apply here? We have such different concepts of individual privacy in the U.S., this notion that our home is our castle, that type of personality. That right of privacy from surveillance in the U.S., we've really seen this gradual erosion of these concepts because we are moving towards a surveillance state, and I don't say that in like in a " 1984" way, because that's inevitable. I've worked with the [U.S. Department of Justice] and the Police Foundation on things like the use of drones in community policing. And that sounds really creepy, but if you think about the use of unmanned aerial vehicles for law enforcement, it's helpful provided the community is aware and on notice—it can help in search and rescue, it can help in all kinds of things. But it poses all of these problems because our courts haven't framed laws, or at least guidelines under common law to figure out how this works. Again, we're reactionary. [At the same time], we all are walking around now with recorders ourselves in our phone, police stopping people from recording them when they're engaged in the course of public duty, and every circuit court has addressed it and is like, "Nope, the public has the right to record the police at all times." We're all in a more heightened surveillance state. It's a two-way street. But the U.S. is much more; that's where we are. We tend to be a little stronger than the Europeans, in that we still perceive the right to electronic privacy. There's a problem, though, because there's such a disconnect between how government is regulated and law enforcement is regulated and what they can lawfully obtain, and what we willingly give over to private industry. We give everything to private industry, and then with the third-party drop trend, if we share it with the app, the app just gives it to the government. Right now the third-party doctrine is a big problem in protecting citizens' privacy. Just by nature, these platforms necessarily require exposure of all our data to third parties, so if we keep the third-party doctrine, we've eviscerated our right to protect from the government seizing information on us.

As a law student, Anne Toomey McKenna worked as a research assistant for a professor who happened to be working on a treatise on wiretapping. McKenna thought she was headed for a career as a civil litigator and took the opportunity as kind of a one-off thought exercise, something that was unlikely to shape much of her career. Quickly, she realized she was wrong. McKenna found the knowledge base she'd developed while working on this system was a far bigger question for the organizations she was working with than she'd expected. Questions about phone call retention quickly evolved into data retention, and before she knew it, she was a cyber law expert. “If you think back to the 1990s, there was really a sea change about how business was run. For lawyers, the fact that everything went to electronic record radically changed law and evidence. These electronic evidence issues kept becoming more and more a part of my practice,” she said. McKenna recently joined Penn State's Dickinson Law and Penn State Institute for CyberScience as a distinguished scholar of cyber law and policy and professor in practice. She'll be heading up interdisciplinary research and learning with students looking at the cyber and data privacy space. Legaltech News recently caught up with McKenna for a Q&A: Legaltech News: How do you think recent technological transformations have translated into law school training? Anne Toomey McKenna: When people graduated from law school in 2010, they could get away with just taking the basic law school classes like civil procedure and common law. You didn't have to have a component of, "How did this change in terms of privacy? How does this change now that everything is online?" Now, if a student graduated and they just had evidence without exposure to electronically searchable information and ESI, they're not prepared to practice law today. It's almost a disservice. That's what really exciting what's really exciting about [Penn State's] Institute for Cyberscience and Dickinson [Law School]. Their focus is that we're preparing for this from the development of technology. They're doing so many cool things with internet of things; they're doing so many cool things with virtual reality and augmented reality. It's so neat to be someone large enough where all the engineers and the software people want to work with lawyers, and they want to do it right. You don't see that many places, maybe because they don't have a law school, but maybe because they're just busy engineering. Do you get the sense that engineering will continue to work faster than lawyers, or that engineers and lawyers will start to work a little more closely in the future? In U.S. law, we tend to be more reactionary to technological development, but I think what's changing that is the EU. With this [General Data Protection Regulation], everybody who wants to do business on a global scale that in any way touches Europeans is required to come into compliance. Have you noticed that every single app is sending you privacy notices? Isn't it so annoying? But at the same time it's so good, because they're trying to be proactive. In the U.S., we tend to regulate in a technology-specific way, meaning that like, cellphones come out and then we create some new legislation, so again, a reactionary response. But with GDPR, by treating data just as data that requires protection in and of itself regardless of platform, it's not technology-specific, it's privacy-specific, data protection specifically. I think that the law, particularly in the U.S., we have just been responding and trying to keep abreast of things. Think of how behind the Supreme Court is in addressing technology. In United States v. Jones, they were just trying to decide GPS tracking, and we're so beyond that with things like IoT. All of our devices are tracking us at all times, communicating with each other. That's one of the cool things about cyber law, is keeping abreast of the technology. We're moving towards U.S. lawyers in particular necessarily being required to understand global approaches to this from a legal standpoint. Any client that wants to have a presence—the positive side of GDPR is that U.S. legislation is going to file on top of that, because our businesses have to comply with it, particularly larger businesses. The differences are also so fascinating in the U.S. about the way we treat data. Medical data—that was HIPAA. Everyone in the legal space was familiar with HIPAA, but they weren't familiar with financial sector law, because it wasn't their space. Now all this information is being defined as personally identifying information, and instead of siloing data as we do in the U.S., it's really much more comprehensive in scope about data itself as opposed to breaking into medical versus financial. What kind of technical background do you think law students need at this point to be competent attorneys? I think that's critical. I think law students should be educated hand-and-hand with information technology students. When I was visiting at Penn State Law earlier this year, I worked with [Information Services and Technology] faculty, and we did a cyber hack simulation where we did a phishing email. We showed the IST students and my law students how a hack goes down, what it looks like from a technical standpoint. We sat there and typed in the breach, showed how the breach occurred, showed how we mimicked and obtained all the passwords for the system. Then what laws come into play? That's how we have to educate people, or we're just not going to develop and educate lawyers who are prepared for what the legal market and the business world and individuals need right now. Lawyers can no longer be just like, " I specialize in law and cyber." Everyone has to have engaged knowledge. It seems like a lot of these issues have broad implications outside of business compliance, in cases like public security and surveillance. How do some of these legal frameworks apply here? We have such different concepts of individual privacy in the U.S., this notion that our home is our castle, that type of personality. That right of privacy from surveillance in the U.S., we've really seen this gradual erosion of these concepts because we are moving towards a surveillance state, and I don't say that in like in a " 1984" way, because that's inevitable. I've worked with the [U.S. Department of Justice] and the Police Foundation on things like the use of drones in community policing. And that sounds really creepy, but if you think about the use of unmanned aerial vehicles for law enforcement, it's helpful provided the community is aware and on notice—it can help in search and rescue, it can help in all kinds of things. But it poses all of these problems because our courts haven't framed laws, or at least guidelines under common law to figure out how this works. Again, we're reactionary. [At the same time], we all are walking around now with recorders ourselves in our phone, police stopping people from recording them when they're engaged in the course of public duty, and every circuit court has addressed it and is like, "Nope, the public has the right to record the police at all times." We're all in a more heightened surveillance state. It's a two-way street. But the U.S. is much more; that's where we are. We tend to be a little stronger than the Europeans, in that we still perceive the right to electronic privacy. There's a problem, though, because there's such a disconnect between how government is regulated and law enforcement is regulated and what they can lawfully obtain, and what we willingly give over to private industry. We give everything to private industry, and then with the third-party drop trend, if we share it with the app, the app just gives it to the government. Right now the third-party doctrine is a big problem in protecting citizens' privacy. Just by nature, these platforms necessarily require exposure of all our data to third parties, so if we keep the third-party doctrine, we've eviscerated our right to protect from the government seizing information on us.This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250