Prosecuting Print Crime: This Law Professor Is Bracing for the 3-D 'Maker Movement'

In this Q&A, Stanford's Mark Lemley explains his take on the new intersections opening between innovation, IP and 3-D printing.

August 08, 2018 at 10:00 AM

5 minute read

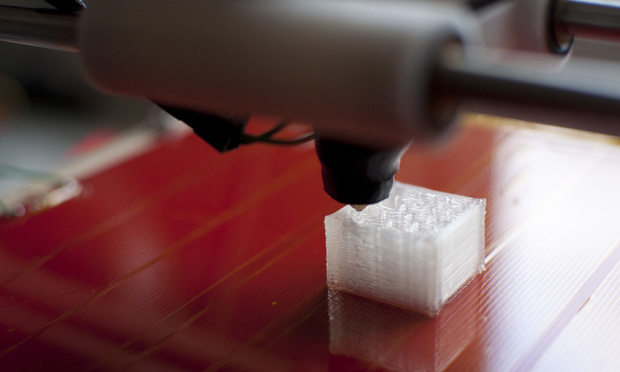

Photo by Zach Zupancic, via Flickr.

Photo by Zach Zupancic, via Flickr.

Law's track record of tackling futuristic foils isn't the strongest, but novel issues are testing its hand. Notable among these is the 3-D printer, a device that in addition to building handbags and houses portends the possibility of guns, knives and other tools threatening in the wrong hands.

Stanford Law professor Mark Lemley takes this notion a few steps further. In an upcoming paper co-authored by Bournemouth University's Dinusha Mendis and Queensland University of Technology's Matthew Rimmer, Lemley and company explore “the legal, ethical, and public policy issues in respect of intellectual property, innovation, regulation,” the abstract says.

Legaltech News recently caught up with Lemley to discuss “print crime” and the novel legal issues sparked by 3-D printing, his analysis of the “Maker Movement” and its potential to change commerce, and how lawmakers and lawbreakers will interact in the years to come.

Legaltech News: What are some novel issues we could see with 3-D printing, given copyright and trademark laws currently on the books?

Mark Lemley: 3-D printing separates design from manufacturing and it democratizes manufacturing. Anyone can share a design anywhere—it's just data. And anyone with the design can make the product in the privacy of their own home. That means that those who want to enforce IP laws are in for a hard time.

Your paper also brings up potential controversies around 3-D printing guns. Are the current disputes playing out in courts and among lawmakers ones you'd say were … predictable? What sort of legal framework do you imagine will result from this use of 3-D printers?

I think the copyright/trademark controversy and the 3-D printed gun controversy are in some sense the same. In both cases, the current or proposed laws are based on restricting access to things, whether they are copyrighted sculptures, patented machines, branded handbags, or plastic guns. The struggles over the last few decades about whether to regulate the internet itself in order to more easily control content on the internet will replicate themselves here with 3-D printers.

It makes sense to ban plastic printed guns and other things replicators can create, like smallpox viruses. But it's a big and unwarranted step from that to banning or regulating the use of 3-D printers themselves. Given the Republican resistance to any form of gun regulation, I actually think the existence of a 3-D printed gun may be the best indication that we won't ban or regulate 3-D printers altogether.

Your paper is slated to analyze 3-D printing under the lens of policy, ethics, regulations and other legal issues. Which arena is the most thorny?

Our forthcoming book, “3D Printing and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Regulation,” tackles these issues from a variety of perspectives and a variety of countries. I think IP issues will be the first to come up in force, but they are also the ones we have the best template for answering because of the similar issues that we've dealt with around the internet.

Considering the plethora of creations likely to come, is there a fine line we may encounter that forces us to choose between innovation and IP? Where do you see U.S. legislators and the courts steering things?

The difficulty of enforcing IP rights against 3-D printing is a real challenge for IP law. But it won't mean no innovation. To the contrary, if the internet is any guide, we will get more creativity than ever before even as IP becomes harder and harder to protect. As I suggested in a paper a few years ago in the NYU Law Review, as the cost of production goes down more and more people create. That's the opposite of what IP predicted, and it may mean that the right role for IP in the future is more limited than it is today.

Do you think the Maker Movement actually might actually match up to something like the industrial revolution in terms of impact?

I do think 3-D printing has the potential to revolutionize the making of many things in the same way the internet fundamentally changed the making and distributing of creative works. One broader challenge is how that affects the economy as a whole. We've already moved away from a world in which people go to stores; now stores bring things to them. 3-D printing may mean that increasingly stores bring you raw materials and you (or your corner print shop) do the rest. That has implications not just for IP, but for how people interact, how cities are configured, how much we drive, and much more.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 1Some Thoughts on What It Takes to Connect With Millennial Jurors

- 2Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

- 3The New Global M&A Kings All Have Something in Common

- 4Big Law Aims to Make DEI Less Divisive in Trump's Second Term

- 5Public Notices/Calendars

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250