Retailers Using Facial Recognition Should Be Wary of Illinois and Followers

Currently there's no federal law regulating facial recognition. However, lawyers say to watch Illinois closely as that state grants its citizens a private right of action measure if its biometric law is violated.

May 02, 2019 at 11:30 AM

4 minute read

In a lawsuit filed last week in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, a lawyer for an 18-year-old New Yorker alleges he was misidentified in a string of Apple store thefts. The suit alleges, among other things, that Apple uses facial recognition technology in its stores.

That practice, while denied by Apple, isn't widely regulated in the U.S. Still, the few state-level biometrics laws that do exist, especially Illinois, should be monitored closely by businesses because of the risks they could pose.

In Bah v. Apple and Security Industry Specialists, Ousmane Bah claims the ordeal of being accused and arrested for theft constituted negligence, emotional distress, slander and other claims brought against Apple Inc. Bah is seeking $1 billion in damages.

According to the suit, a New York City Police Department detective said he viewed surveillance video from a Manhattan Apple store Bah was accused of stealing from, and the suspect and Bah didn't look alike. He also explained Apple's security technology identifies theft suspects using facial recognition technology,

A request for comment from Apple regarding its use of facial recognition technology in its retail stores was not answered by press time but, according to The Verge, the retailer has said it doesn't use facial recognition technology in its stores.

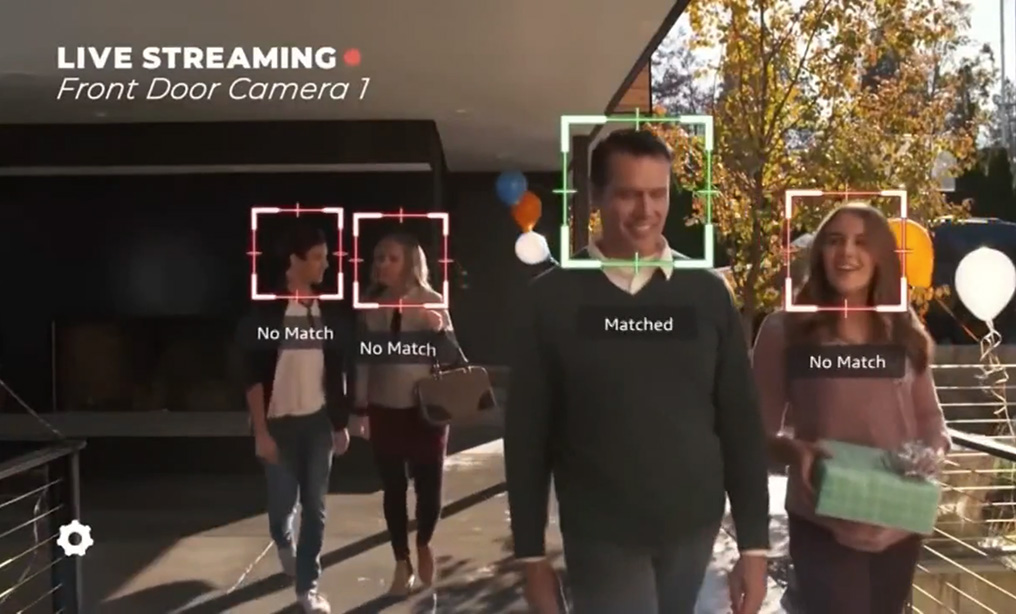

To be sure, facial recognition in stores is a growing trend, according to a 2017 CNBC article.

This may be in part because retailers considering using facial recognition software in U.S. stores won't find many regulations governing the technology. Indeed, outside of Washington state, Texas and Illinois, no other state currently has a law governing facial recognition software. Likewise, there's no federal regulation concerning biometrics, although the U.S. Senate introduced the Commercial Facial Recognition Privacy Act of 2019 in March.

But of the three state biometric laws, Illinois' Biometric Information Privacy Act law differs the most significantly by allowing a private cause of action for violation of the law. Such private actions, which are available to Illinois residents and can be rolled into a class action suit, makes facial recognition a greater danger in Illinois, lawyers said.

“Because Illinois is still the only state to have a private right of action and the consequence is $1,000 for negligence or $5,000 for intentional or reckless violations or actual damage … there's a great risk to using that technology in a state like Illinois,” said Mary Smigielski, a Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith partner and co-chair of the firm's Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act practice group.

“You only need a technical violation,” Smigielski added. “You don't need to have a data breach or have the information stolen, just the mere fact that you proceeded without having consent is violation.”

Indeed, the Illinois Supreme Court held earlier this year that violation of the law, which requires written consent and notification to collect and use an individual's biometric information, can have a right of action and actual damage isn't required to be aggrieved. Some lawyers predicted the case could open the floodgates for biometric class action suits in Illinois.

If a retailer does use facial recognition technology in Illinois, the company must have written consent from customers and a readily available public policy explaining what the retailer is collecting, why it is collecting, consent to share it and “can't otherwise profit from it,” said Justin Kay, a Chicago-based Drinker Biddle & Reath partner.

While most states do not have any biometrics laws, some argue that following the guidelines of the few that do is just good business.

Jeffrey Neuburger, a New York-based Proskauer Rose partner, said although New York state doesn't have a biometric law, he would recommend a business provide public notice of facial recognition technology being used in its store.

“I think it takes away some of the creepiness factor if people ultimately find out they are using facial recognition,” he said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 1Gunderson Dettmer Opens Atlanta Office With 3 Partners From Morris Manning

- 2Decision of the Day: Court Holds Accident with Post Driver Was 'Bizarre Occurrence,' Dismisses Action Brought Under Labor Law §240

- 3Judge Recommends Disbarment for Attorney Who Plotted to Hack Judge's Email, Phone

- 4Two Wilkinson Stekloff Associates Among Victims of DC Plane Crash

- 5Two More Victims Alleged in New Sean Combs Sex Trafficking Indictment

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250