San Francisco DA Office Attempts Novel Feat: Using AI to Combat Bias

Algorithms are coming to the San Francisco District Attorney's Office. In a bid to combat implicit bias, artificial intelligence-backed software will redact race information from police incident reports before prosecutors make their initial charging decision.

June 19, 2019 at 11:52 AM

4 minute read

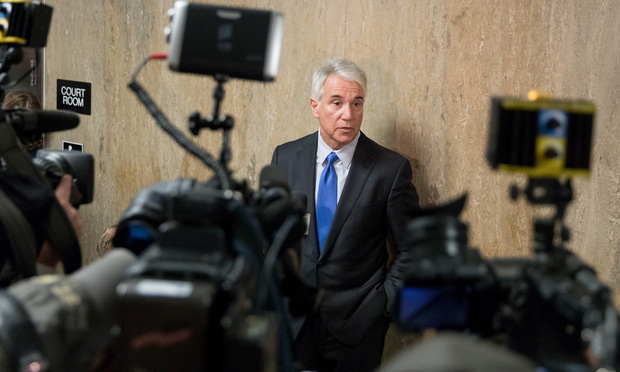

San Francisco District Attorney George Gascon at the sentencing of Jose Zarate.

San Francisco District Attorney George Gascon at the sentencing of Jose Zarate.

As the debate continues over the bias of algorithms and artificial intelligence tools used in important matters ranging from loan approvals to prison sentences, the San Francisco District Attorney's Office is taking a different approach. Last week, the office announced it is turning to an artificial intelligence-powered bias mitigation tool to redact any race-specific language before a police officer's incident report hits a prosecutor's desk.

The software is an effort to remove implicit bias from prosecutors' charging decisions. But observers say that monitoring of the program will be needed as algorithms are only as objective as the information they are programmed with.

Scheduled to begin in July, the San Francisco DA's Office will implement an open-source bias mitigation tool that will automatically scan and redact race information and “other details that can serve as a proxy for race,” announced San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón in a press statement.

Direct race or proxy race information includes first and last names, eye and hair color, addresses and the police officer's precinct. In the first incident reports DA prosecutors see, the bias mitigation tool automatically replaces the race-suggestive information with generic labels like race, name and neighborhood.

The prosecutor will make their initial charging decision based on the redacted version of the police reports. After that initial decision is made, they are then shown the fully unredacted reports and any “non-race blind information,” such as video footage, according to the DA's Office. If prosecutors change their original charging decisions they have to document what additional evidence caused their update. The DA's Office said it will collect and review those updates to identify the volume and types of cases where charges changed from the initial decision.

While those endeavors claim they have good intentions, some have noted algorithms can have the same built-in biases as the people or policies used to code the software.

“Just because it's a system that doesn't—in each instance—apply its own biases, it doesn't mean it doesn't have that biases hardwired into it,” said Fenwick & West intellectual property partner Stuart Meyer. “That doesn't mean it'll get rid of biases.” He added, “It just shows that implicit bias can be built into those systems just as easy as human beings. It all depends on how we train those systems.”

Explainability and transparency are key features of any artificial intelligence software, Meyer said, especially if its decisions are consequential.

For the DA Office's part, office spokesperson Max Szabo said the bias mitigation tool was previously tested and there are ongoing audits scheduled as well.

Alex Chohlas-Woodis, deputy director of the Stanford Computational Policy Lab and a member of the team that created the bias mitigation tool, also noted the importance of receiving feedback from prosecutors to find out how well the tool is at redacting information.

While a truly unbiased algorithm is unlikely, Meyer argued proactive measures, including monitoring results, are essential for ensuring a software does no harm.

“It's important to recognize that human decisions still get perpetuated through artificial intelligence,” he said. “But the good news is people can think about those things in advance and train to engineer the bias out of them in advance.”

The tool being deployed at the DA's office was created by the Computational Policy Lab for free at the suggestion of Gascón in February. Gascón has been interested in the implications of race in the criminal justice system previously and thought there was more the office could do to curb implicit bias, Szabo said.

Szabo added that the initiative not only marks the start of using a bias reduction tool in the prosecutor's office, but a step toward digitizing police incident reports. Currently, many of the documents prosecutors use are paper-based, while the Stanford tool requires computer access.

The new tool and process will be used in all cases, but for the initial outset they will only be used for approximately 80% of the office's caseload, which is generally felony cases, Szabo said.

Stanford's Computational Policy Lab is no stranger to partnering with government agencies and deploying AI-backed software to address public policy. Its previous projects include an analysis of over 100 million traffic stops in the U.S. to provide data to policymakers to improve interactions between the public and police; a machine learning-powered test to identify and track potential bias in organizations; and risk assessments for bail reform.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 1When Words Matter: Mastering Interpretation in Complex Disputes

- 2People in the News—Jan. 28, 2025—Buchanan Ingersoll, Kleinbard

- 3Digital Assets and the ‘Physical Loss’ Dilemma: How the Fourth Circuit’s Ruling on Crypto Theft Stands at Odds With Modern Realities

- 4State's Expert Discovery Rules Need Revision

- 5O'Melveny, White & Case, Skadden Beef Up in Texas With Energy, Real Estate Lateral Partner Hires

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250