Discovery Motions in the Age of E-Discovery: A Look at the Golden State

During its initial drafting, many of public reviewers of the Electronic Discovery Act expressed concerns that the proposed legislation would overburden the courts and litigants with motions for protective orders. In practice, the results are mixed.

June 25, 2019 at 09:30 AM

5 minute read

Historically speaking, pretrial discovery is a relatively recent addition to common law. Its emergence dramatically changed the course of civil cases, seemingly helping to render the process more fair, more efficient, more transparent. In fact, most civil cases filed in the United States are now settled through discovery—that is, without a trial. And its importance in the litigation process keeps expanding, often acting as its most time-consuming and expensive stage.

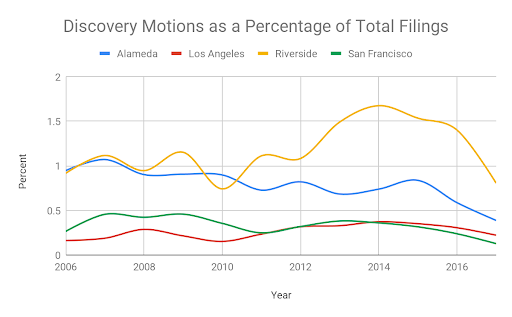

Yet, the share of discovery motions filed throughout the Superior Courts of California in the past ten years has remained relatively constant. (Riverside County is a notable exception. More on that below.) More and more of the information sought through these motions is now created and stored in electronic formats. These formats have left behind trails of electronic fingerprints, metadata that cannot be captured in paper printouts. They have also enabled new search functionalities, new ways to index and coordinate disparate pieces of information. As such, the civil rules and procedures guiding discovery have needed updating. The courts required new policies, standards that could help eliminate the uncertainties associated with the discovery of electronically stored information.

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed the Electronic Discovery Act on June 29, 2009. This act took immediate effect throughout the State of California, defining “electronically stored information” and establishing procedures for its production during the discovery process. Although the text closely follows the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) and their guidelines for e-discovery, there are important differences, most notably with regard to the production of inaccessible data.

The FRCP classifies electronically stored information as either accessible or inaccessible. Requesting parties must review electronically stored information from accessible sources before seeking electronically stored information from inaccessible ones. A requesting party must demonstrate good cause before any inaccessible data can be collected and searched, a policy that requires the requesting party to petition the federal court for an affirmative order to search inaccessible electronically stored information.

In contrast, the Electronic Discovery Act requires the courts to treat all electronically stored information as accessible. All that information stored in dusty, obsolete devices must be reformatted for contemporary devices. All those gigabytes of data stored in servers near and far must be made available.

This minute difference in classificatory schemes shifts the obligations of requesting and responding parties. According to the FRCP, if a requesting party wants access to inaccessible electronically stored information, then they must file a motion to compel the production of documents. However, in California, the Electronic Discovery Act places the burden on the responding party, who must file a motion for a protective order detailing how the specific data source is inaccessible due to undue burden.

During its initial drafting, the Electronic Discovery Act was circulated amongst law firms and city attorneys, legal associations and chambers of commerce, government commissions and attorney licensing agencies. Many of these public reviewers expressed concerns that the proposed legislation would overburden the courts—as well as litigants—with motions for protective orders. They predicted that responding parties would automatically be required to file for a protective order at the outset of every civil action, as the absence of a two-tiered classificatory system strikes the wrong balance between requesting and responding parties.

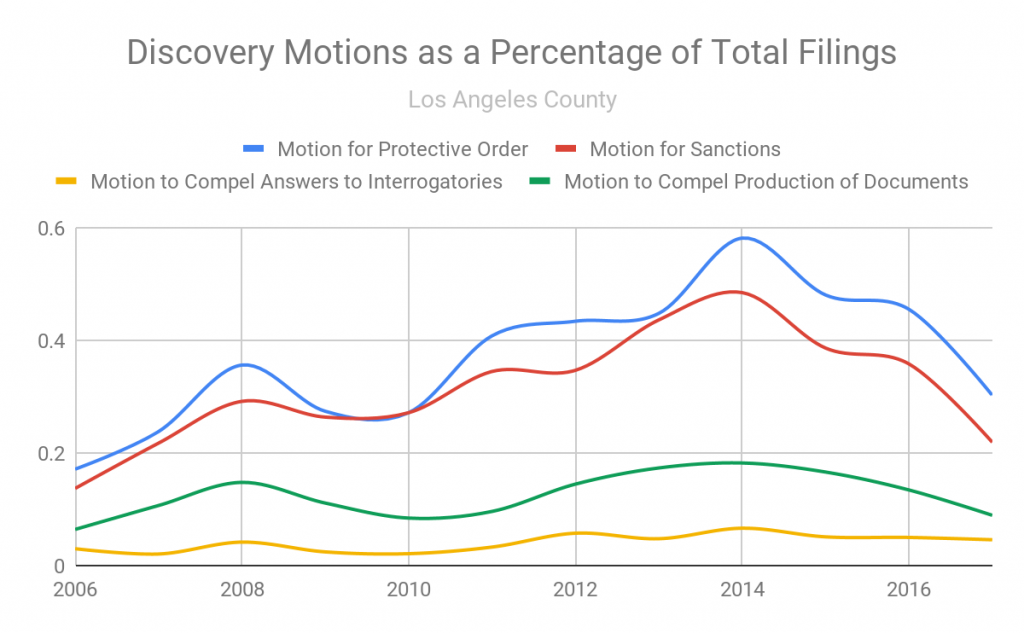

In Los Angeles County, these concerns rang a little bit true. After the Electronic Discovery Act passed in 2009, the percentage of motions for protective orders increased from 0.26 percent to 0.58 percent.

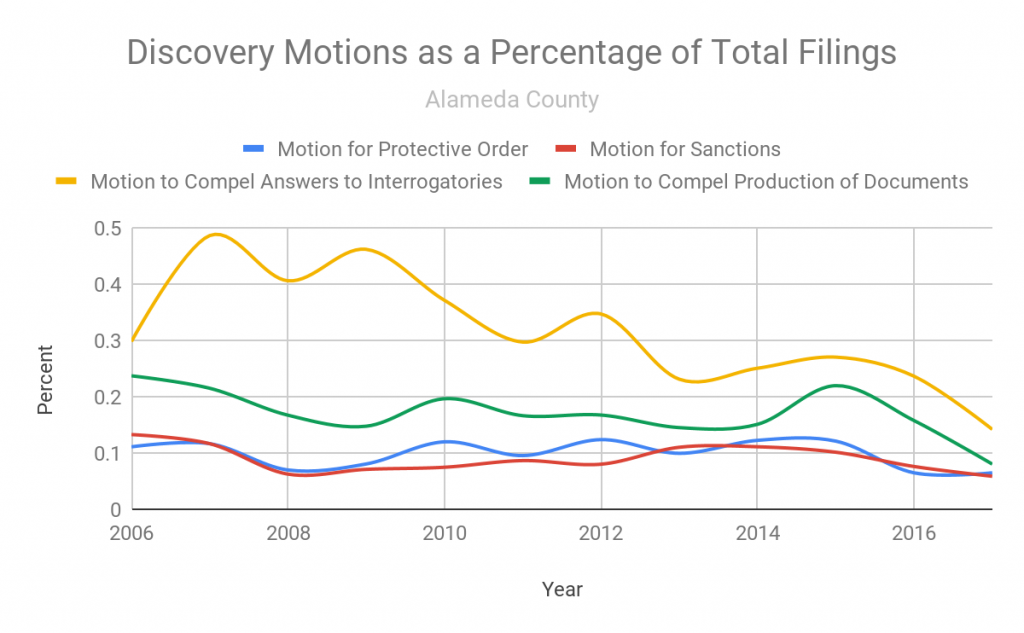

The story, however, is not so simple. Consider Alameda County. The percentage of motions for protective orders stayed relatively constant, hovering around 0.1 percent until 2015.

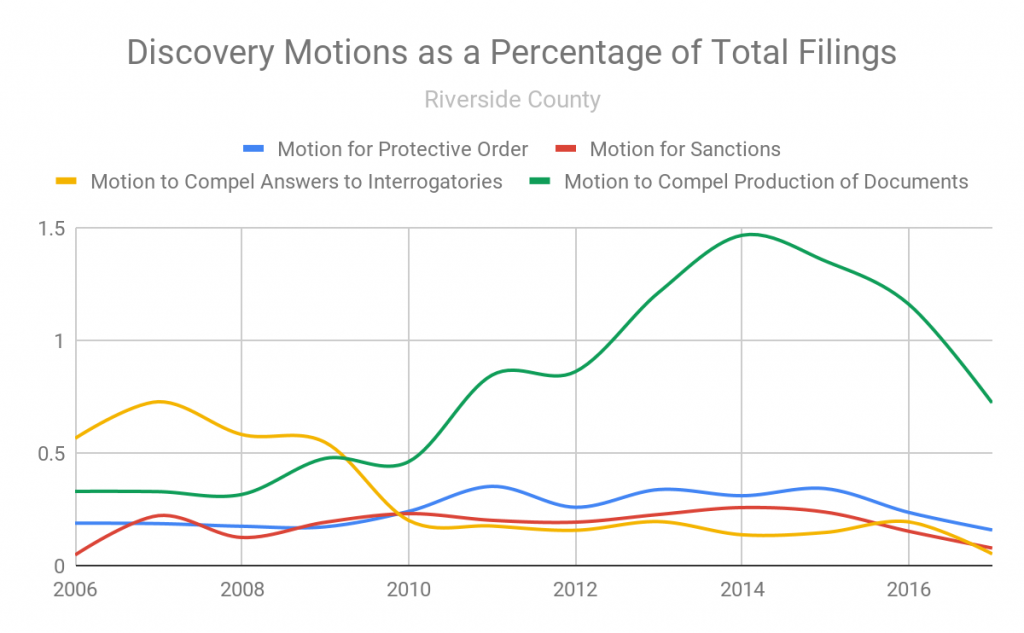

And then there is Riverside County. The percentage of motions for protective orders experienced little change after 2009. Yet, the percentage of motions to compel production of documents ballooned, rising from 0.48 percent in 2009 to 1.5 percent in 2014.

Historical data on the number of discovery motions filed throughout the Superior Courts of California offer a glimpse into how legislative changes in electronic discovery affected litigation strategies. Has a single-tiered classificatory scheme caused litigants to file more protective orders? More motions to compel? The unexpected effects of the Electronic Discovery Act are a reminder about the importance of studying litigation practices.

Such research is useful for legal practitioners, helping them to predict the kinds of responses they are likely to receive from opposing parties. But it can also help reviewers of the legal process map the burdens placed on different parties, maps that allow us to think about the question: At whose expense does fairness and efficiency comes?

Nicole Clark is the Founder/CEO of Trellis: Legal Intelligence, a VC-backed legal tech startup. Prior to founding her company, she practiced as a business litigator and employment attorney at mid-size litigation boutiques and AM100 firms.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 1Understanding the HEMS Standard in Trusts

- 2Mergers Are About People, Not Paperwork: Here’s Why

- 3Wachtell Partner Leaves to Chair Latham's Liability Management Practice

- 4Morris Nichols Partners to Be Involved With PLI Program

- 5How I Made Practice Group Chair: 'Cultivating a Culture of Mutual Trust Is Essential,' Says Gina Piazza of Tarter Krinsky & Drogin

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250