The Best Way to Notify Class Members? It's Not Email, FTC Says

The report comes as new federal rules have encouraged electronic notices in class action settlements. But the report found that email notices had a lower claims rate than did traditional materials sent in the mail.

September 23, 2019 at 01:00 AM

9 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

U.S. Federal Trade Commission building. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission building. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM.

For years, attorneys pushed the federal courts to embrace the use of email to notify class members about a settlement. They were cheaper, they argued, more modern, and less likely to end up in the trash. But a comprehensive study out this month by the Federal Trade Commission found that emailed notices weren't getting more consumers to sign up for their refunds—in fact, they're making things worse.

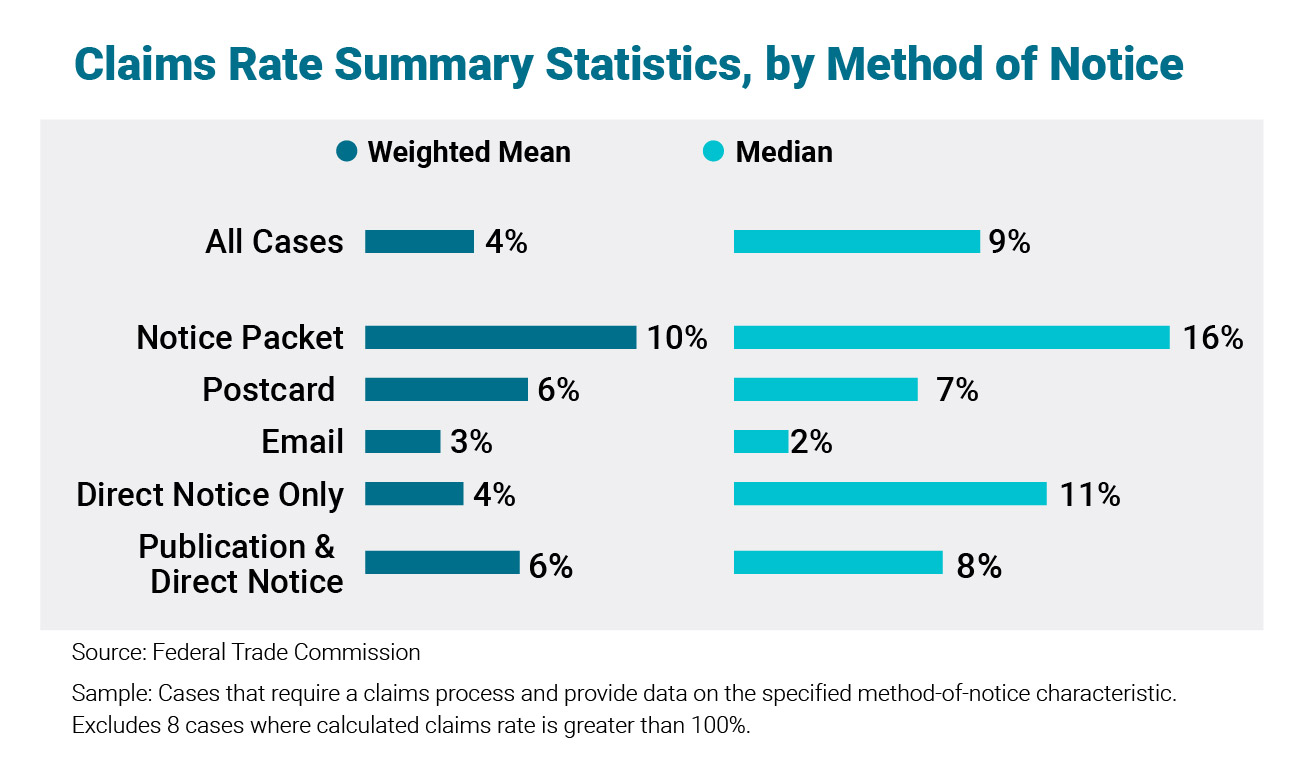

The report, called "Consumers and Class Actions: A Retrospective and Analysis of Settlement Campaigns," found that email notices resulted in a median claims rate of 2% and a mean claims rate of 3%, weighted by the number of class action members. That is far lower than traditional packets of class action materials sent by U.S. mail, which resulted in a 10% weighted mean and 16% median, the FTC report said.

That finding is surprising, according to lawyers and others who practice in class actions. And it comes despite a new rule enacted last year that encouraged lawyers to use more electronic notices.

"Everyone was very excited about using email in the future because it was so much cheaper, and the rule has changed to make it more allowable," said Brian Fitzpatrick, a professor at Vanderbilt Law School who focuses on class actions. "Given that people seem to disregard emails at a higher rate, it calls into question whether we should go further down that path."

The report also found that a combination of notice methods, such as email and newspapers, for instance, did little to improve the claims rate. Yet the words used in email notices did change how people responded, the report found, and suggested rephrasing the subject lines.

"It's very helpful to know the words you're using matter in terms of initiating action," said Elizabeth Cabraser, of San Francisco's Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein. "I was fascinated by that."

To be sure, the report had numerous caveats, many of which the FTC noted in detail when summarizing its research. For one thing, the report relied only on class action settlements in which direct notices were available. In many cases, particularly involving lower-priced consumer goods, lawyers and companies do not have a way to identify individual class members in order to send them a direct notice. As a result, those cases tend to have lower claims rates. Experts said that could be why the FTC's report found overall claims rates to be on the high side: a 9% median and 4% weighted mean.

Still, the claims rates are encouraging to lawyers who often see much lower percentages.

"If you think about direct mail campaigns in other areas, where someone is trying to initiate other types of actions, such as buying a product or making a donation, it's usually 1%," Cabraser said. "That's considered good. Nine percent is very good indeed."

The report, part of the FTC's Class Action Fairness Project, is one of the most extensive yet on class action settlements. In 2017, the FTC subpoenaed seven claims administrators for data. The project's idea was to improve class action settlements for consumers while making sure lawyers and defendants aren't benefiting at their expense.

The FTC plans to take comments on the findings through Nov. 22 and host a public workshop Oct. 29 in Washington, D.C.

The report uses two sets of data to complete two studies: 149 consumer class actions provided by the claims administrators, called the "administrator study," and the findings of its own "notice study," an internet survey of 8,000 randomly selected participants who received email notices about a fictitious class action settlement.

The FTC report could be among the first research to provide an impartial view on class action settlements, which engender intense arguments about abuse and advocacy and frequent legislation on Capitol Hill, lawyers say. It also could provide guidance to lawyers and judges, many of whom are increasingly scrutinizing class action settlements. But that's not all who could benefit.

"I could also see it perhaps informing the Department of Justice," Fitzpatrick said. Under the Trump administration, the DOJ has used its authority under the Class Action Fairness Act to object to some class action settlements. "I assume the whole point of this is to try to bring to light some better ways of doing things that they hope the courts will insist upon, and maybe the Department of Justice could facilitate that through objections."

The report found that, not only did email notices perform worse than mailed packets, but that even postcards worked better. According to the report, postcard notices resulted in a median claims rate of 7% and a weighted mean of 6%.

The report comes as the U.S. Judicial Conference's Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure imposed a new rule specifying that sometimes "electronic means, or other appropriate means" could be appropriate to fulfill the Federal Rule 23 of Civil Procedure's mandate to provide the "best notice that is practicable." Lawyers saw the change as an opportunity to use less expensive, and perhaps more efficient, notices through emails or social media.

Andrew Trask, of counsel at Shook, Hardy & Bacon in Los Angeles, said the report's findings about email notices were surprising given the enthusiasm behind their use. But he suggested that consumers might be more adept at identifying legitimate notices in the mail than they used to be.

"By contrast, it may be more difficult to distinguish legitimate emailed class notices from Nigerian princes or Microsoft chain mails," he wrote in an email.

One person who wasn't surprised about the report was Todd Hilsee, principal of The Hilsee Group in Philadelphia. He's a class action notice expert who argued against federal rules encouraging electronic notices. He called the FTC report an "important voice" in the debate over class action settlement notices.

"The rules encouraging judges to utilize electronic notice, even when there is the availability and possibility of a postal mailing list, were completely unsupported by any study that suggested that email was more effective," he said.

He also wasn't surprised that claim notices sent through U.S. mail performed better. He said mailed notices are more intrusive and that mailing addresses are easier to track than email notices.

Postcards, although less effective at getting a higher claims rate, are commonplace because they cost less—something that both lawyers and claims administrators hoping to win the lowest bids both prefer, Hilsee said.

"It's not because they're better," he said of postcard notices. "Everybody knows a regular envelope with easy-to-read print, with a claim form enclosed and separate envelope with postage on it, that's going to be head and shoulders more responsive—it just makes common sense—than a postcard with tiny fine print that doesn't include the claim form and says, 'Hey, go to this website.'"

But Cabraser questioned the report's findings on email notices, which she said have been shown anecdotally to improve claims rates. She said email notices have improved in the past five years, particularly when it comes to avoiding a class member's spam filters. The FTC's data comes from settlements between 2013 and 2015.

"It may be true that earlier email campaigns were not as effective," she said. "And, in fact, we've studied those campaigns, and that's how notice expert providers realized there were things you had to do to get the email opened and to get it read and to devise tracking for that. That's a work in progress, but I think progress has been made on that."

Moreover, she said, people tend to keep their email addresses, even if they move, which reduces the percentage of returned notices sent to mailing addresses. The report notes that notices sent through packets via U.S. mail might not cause higher claims rates but, instead, reflect other factors, such as companies that have more detailed customer records.

Cabraser also questioned the report's finding that supplementing the emails with published notices, such as magazines and TV ads, made little difference in the claims rate.

"We realized that multimedia repetitive campaign will be more effective," she said, noting that, in the Volkswagen emissions case, the most effective notice was an email blast combined with a postcard. "Sooner or later, the class member will take notice."

One thing that does make a difference: The words lawyers use in the notices. According to the report, notices in "plain English," such as "refund" and "cash," resulted in higher claims rates.

The claims rates were slightly better when the email notices were longer, but there was no difference between class members who received $10 from the settlement, versus more than $200, the report said. The notice study found that class members were more likely to open an email that referenced a refund but less likely to open an email that referenced the exact dollar amount. That could be because more than half of the recipients thought the email with the dollar amount was an advertisement, the report said.

Those findings show that people have reasons for not making claims in a class action settlement other than the popular belief that they will not receive very much, Cabraser said.

"It's not about the money, but the nature of the case and the product," she said. "Some folks are much more likely to take action and participate depending on the nature of the product."

The notice study found that references to a "class action" got people to open the email at a higher rate if it was in the sender's address but not if it was in the email header. And putting a court seal on the notice added only a little bit of credibility.

"That goes to show it's going to be really, really hard to overcome people's desensitized anti-spam nature," Fitzpatrick said. "People do not look at emails unless they already know the sender."

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllTrending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250