Gorsuch Comments Reveal Problematic Reality: Judges Lack E-Discovery Education

E-discovery had a brief cameo in a U.S. Supreme Court argument that could reshape presidential oversight. But e-discovery experts say Justice Neil Gorsuch's comments underscore a broader misconception of e-discovery in the judicial branch.

May 18, 2020 at 02:52 PM

5 minute read

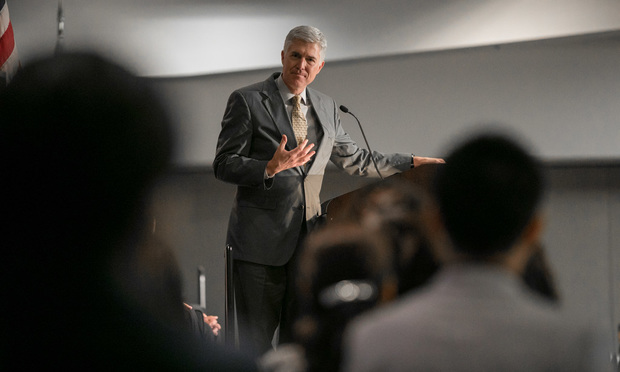

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, United States Supreme Court at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Conference in San Francisco

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, United States Supreme Court at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Conference in San Francisco

During last week's historic U.S. Supreme Court argument over subpoenas of President Donald Trump's financial records, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch made an e-discovery comment that caught some court watchers' attention.

On May 12, the justices heard arguments in Trump v. Mazars regarding three U.S. House of Representatives investigation committees' subpoenas for Trump's financial documents. Participating remotely via phone conference, Gorsuch asked House general counsel Douglas Letter if there's a limiting principle to avoid misusing subpoena power.

"And it can't be burdensome," Gorsuch said, according to the Supreme Court's transcript. "I heard [burden], was your third, but in an age where everything's online and can be handed over on a disk or a thumb drive, that—that—that much pretty much disappears too."

To be sure, while the case had nothing to do with e-discovery's burden, Gorsuch's statement highlighted how most judges still lack in-depth e-discovery understanding. For some, this also underscored the need for ongoing training and the elevation of lawyers with e-discovery experiences to the bench.

"I think it highlights a few misconceptions about electronic discovery that it's a simple touch of a button and that you can comply with all your discovery obligations," said Lloyd Freeman, an Archer partner and Drexel University Thomas R. Kline School of Law e-discovery professor.

He added the variety of electronic data potentially subject to e-discovery is only growing, and judges and counsel can't afford to not understand the evolving process.

"That's why I say it's very important for all judges and practitioners to sign up for those CLEs and learn those rules and how they affect the practice of law. It can get quite expensive and time-consuming and too much of a burden for you to comply with."

Prior to their admission to the bar, law school students should be exposed to e-discovery training, Freeman argued. "I think that law schools should take heed to what the justice's comment underscores the need for law schools to add e-discovery."

To be sure, Freeman did note e-discovery is a "relatively new course for any law school to have." Indeed, e-discovery wasn't even in its infancy until the early 2000s, a decade after Gorsuch graduated from Harvard Law School in 1991.

Still, after practicing law as an associate and partner at Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick and being appointed to the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in 2006, Gorsuch and other federal court of appeals judges are rarely exposed to e-discovery.

District judges usually leave discovery issues to magistrate judges to handle, wrote Driven Inc. information governance and e-discovery consultant Philip Favro in an email.

"With relatively few opportunities to consider issues surrounding electronic discovery, it's understandable that many district judges and appellate judges—like Justice Gorsuch—are not acquainted with the law, rigors, or technology associated with electronic discovery," Favro said. "Nevertheless, most district judges and appellate judges still correctly decide the issues."

Like Freeman, Favro said judges can take part in educational programs to further their understanding of e-discovery.

However, DLA Piper special counsel and former Southern District of New York U.S. Magistrate Judge Andrew Peck wasn't sure such programs could completely close the knowledge gap.

He pointed to the varying support for discovery training in state courts compared to federal courts, and noted that even when training is available, it may not be applicable.

"There's also a big difference between sitting in a classroom and hearing about this when you don't have a particular issue in front of you and remembering what you heard a year or two years later when that issue may actually come before you," he said. Along with leading e-discovery seminars for judges, Peck also granted the first judicial approval for the use of technology assisted review in 2012′s Da Silva Moore v. Publicis Groupe.

Christine Payne, a partner at e-discovery firm Redgrave, noted judges who became leaders in e-discovery "were on the bench when e-discovery really arose as a major issue in the law. A lot of them themselves didn't actually perform e-discovery in private practice. So that's going to change eventually as more spots on the bench open up and people who practice now become judges themselves."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Troutman Pepper, Claiming Ex-Associate's Firing Was Performance Related, Seeks Summary Judgment in Discrimination Suit

- 2Law Firm Fails to Get Punitive Damages From Ex-Client

- 3Over 700 Residents Near 2023 Derailment Sue Norfolk for More Damages

- 4Decision of the Day: Judge Sanctions Attorney for 'Frivolously' Claiming All Nine Personal Injury Categories in Motor Vehicle Case

- 5Second Judge Blocks Trump Federal Funding Freeze

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250