Navigating A New Realm: AI and Patent Law

While the current law permits patenting of inventions that utilize AI, significant challenges exist when it comes to patenting inventions that are created by AI.

July 16, 2020 at 11:00 AM

8 minute read

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Back in 1955, John McCarthy coined the term "artificial intelligence" to represent the science of developing intelligent machines. The following year, McCarthy established AI as a field when he organized the Dartmouth Conference to operate under the "conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of [human] intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it." While AI as a term and science may not be new, certain legal issues surrounding the patenting of AI inventions certainly is at its infancy.

What are "AI Inventions"?

The term AI inventions is an umbrella that covers two categories: inventions that utilize AI and inventions that are created by AI. The first category—inventions that utilize AI—broadly covers inventions of software and/or hardware used to run the AI. These inventions relate to AI algorithms, collection, storage, and use of training data (i.e., input data into the AI), hardware used to execute the AI algorithms or operate with training data, and applications of AI (i.e., uses for the data output by AI). In short, inventions that utilize AI "include anything under the sun that is made by man," subject to exclusions for laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas, of course.

The second category—inventions that are created by AI—on the other hand, encompasses solutions to problems identified by the AI itself or those identified to the AI by a human. One of the few examples available today are the solutions identified by Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience (DABUS), a Creativity Machine. Its creators describe DABUS as the result of the constant combining and detaching of multiple disconnected neural networks that, eventually, coalesce into structure representing complex concepts. These concepts connect with other concepts to represent the anticipated consequence of any given concept in a manner reminiscent of what can be considered a stream of consciousness. Through this process, DABUS "invented" a new type of beverage container and a flashing device used to attract attention, both of which are subject of patent applications filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the European Patent Office (EPO), and the U.K. Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO). All of these applications have since been rejected because the current patent law of the three jurisdictions limits inventors to "natural persons."

Challenges in Patenting AI Inventions

Each category of AI Inventions carries its own patentability challenges. Inventions that utilize AI, for example, are patentable assuming the claims meet all the necessary requirements of patentability, i.e., novelty, non-obviousness, and sufficient written description/enablement. In fact, DABUS, discussed above, is itself patented.

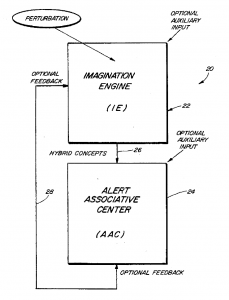

Fig. 1, U.S. Pat. No 5,659,666

Fig. 1, U.S. Pat. No 5,659,666Applicants seeking to patent such inventions will face the ever-evolving patent-eligibility limitations in their applicable jurisdiction. For example, in the U.S., applicants must navigate agency and case law developments to avoid claiming patent-ineligible abstract ideas, especially where the claims are directed to algorithms or specific uses of what may be perceived as an existing technology.

Inventions that are created by AI, on the other hand, present additional challenges. U.S. patent law, for example, defines the act of invention as the mental step of conception. (Per Townsend v. Smith, conception is the "formation in the mind of the inventor of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention." According to the USPTO, only a "natural person" can engage in the mental step of conception and, thus, only a "natural person" can be named an inventor.

The inquiry does not end here, however. A possible mechanism to secure patent protection in these circumstances may come down to how one views a solution to a problem that is created by AI. The premise is rather simple: A "natural person" developed the algorithm/wrote the code that created the AI. The "natural person," or the AI itself, then identified a problem which, in turn, led to the AI to derive the solution. The question as to whether the solution is patentable, under the current legal rubric, is whether the "natural human" or the AI invented the solution? Did the "natural person"—one that created the AI—invent the solution, because the solution could not have been identified by the AI but-for the "natural person" and the AI is merely reducing the solution to practice? Or, on the other hand, is the solution the result of the AI's "organic" growth and maturation, which is outside of the control or direction of the "natural person"? The current state of the law does not provide a clear answer.

Protecting Inventions that are Created by AI

The current challenges to patenting inventions that are created by AI do not mean that such inventions should be left unprotected. It is possible that legislative changes may be needed as the full scope of AI's capabilities become better understood. In the meantime, however, trade secret protection may be a viable option where it is determined that patent protection is unavailable. The invention can be maintained as a trade secret so long as its public disclosure can be prevented. Knowledge of the invention can be limited to reduce the breadth of internal disclosure and employees "in the know" can be subject to non-disclosure agreements or other restrictions to reduce the likelihood of misappropriation. Of course, public disclosure may not be preventable, especially where the invention, or its use, is detectable outside of the organization. When this happens, the long-term viability of the trade secret may be jeopardized by the possibility of independent invention by another outside the organization or reverse engineering.

Another option is to file applications where both human and AI conceived different parts of the invention. Because; in this case; a "natural person" has conceived the invention, the USPTO should not reject these applications for lack of inventorship.

We are only beginning to scratch the surface of the various legal implications that AI will have on patent protection. While the current law permits patenting of inventions that utilize AI, significant challenges exist when it comes to patenting inventions that are created by AI. The good news is that these challenges are not insurmountable and can, and likely will change as more and more AI applications are being filed and AI takes a more prominent position on the center stage.

This article reflects only the present personal considerations, opinions, and/or views of the authors, which should not be attributed to any of the authors' current or prior law firm(s) or former or present clients.

Eugene Goryunov is a partner in the Intellectual Property Practice Group in the Chicago office of Haynes and Boone and an experienced trial lawyer that represents clients in complex patent matters involving diverse technologies. He has extensive experience and regularly serves as first-chair trial counsel in post-grant review trials (IPR, CBMR, PGR) on behalf of both Petitioners and Patent Owners at the USPTO.

David L. McCombs is a partner in the Intellectual Property Practice Group in the Dallas and Washington, D.C. offices of Haynes and Boone and is primary counsel for many leading corporations in inter partes review (IPR) and is regularly identified as one of the most active attorneys appearing before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

Dina Blikshteyn is of counsel in the Intellectual Property Practice Group in the New York office of Haynes and Boone. Dina's practice focuses on post grant proceedings before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, preparing and prosecuting domestic and international patent applications, as well as handling trademark and other IP disciplines.

Jonathan Bowser is of counsel in the Intellectual Property Practice Group in the Washington, D.C. office of Haynes and Boone. He is a registered patent attorney focusing on patent litigation disputes before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) and federal district courts.

Raghav Bajaj is a partner in the Intellectual Property Practice Group in the Austin office of Haynes and Boone. His practice focuses on patent office trials before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), including inter partes review (IPR) and covered business method (CBM) review proceedings, representing both petitioners and patent owners.

Angela Oliver is an associate in the Intellectual Property Practice Group in the Washington, D.C. office of Haynes and Boone. She focuses her practice on patent appeals before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and post-grant proceedings before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View AllLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 2Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

- 3Freshfields Hires Ex-SEC Corporate Finance Director in Silicon Valley

- 4Meet the SEC's New Interim General Counsel

- 5Will Madrid Become the Next Arbitration Hub?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250