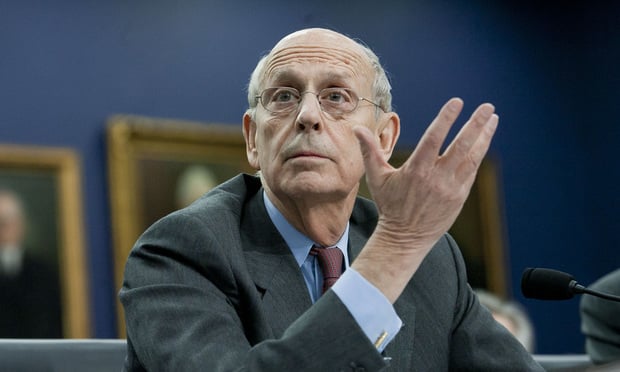

'With Respect,' Justice Breyer Blasts Immigration Ruling in Rare Oral Dissent

Reading from his 33-page written dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer signaled alarm with the majority's holding that asylum seekers and other arriving aliens can be detained indefinitely without bond hearings. He called the DOJ's position that the immigrants aren't technically on U.S. soil a “legal fiction.”

February 27, 2018 at 02:15 PM

4 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

When U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer began to read from his dissent in a key immigration case Tuesday, he warned that his recitation would be long, but said the principles were clear.

Breyer went on to criticize the court's majority decision in Jennings v. Rodriguez that detained aliens do not have a right to periodic bail hearings. Citing the Declaration of Independence and Blackstone, among other sources, he asserted that confined aliens in this country have a basic right of due process to seek bail.

In his 33-page written dissent, Breyer accused the Justice Department of embracing the “legal fiction” that constitutional due process protections don't apply to asylum seekers or other arriving aliens “because the law treats arriving aliens as if they had never entered the United States; hence they are not held within its territory. This last-mentioned statement is, of course, false.”

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor joined Breyer's dissent. A splintered majority agreed with different parts of the decision written by Justice Samuel Alito Jr. (left), overturning a 2015 ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Justice Elena Kagan was recused, probably because of her prior role as U.S. solicitor general.

The American Bar Association filed a brief in support of aliens in the case, asserting that “procedural safeguards are … critical where, as here, immigrants are awaiting a civil proceeding … to determine whether or not they may be removed from this country.”

It was the 20th time Breyer read a dissent from the bench since joining the court in 1994, according to a scholarly tally—less than once a year, but in recent years his dissents have been more frequent.

Oral dissents are rare, but when it does occur, it follows a long tradition of justices signaling their discontent with what the majority has done, and hoping that their dissent will plant a seed for future reconsideration.

Some oral dissents, such as those by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, are angry or sarcastic or both, making it hard to imagine how he and the author of the majority opinion could get along the next day. “No one I know has been as vituperative as Scalia,” court scholar Mel Urofsky said in 2015, discussing his book ”Dissent and the Supreme Court.”

Breyer usually has a more mournful tone when he reads from his dissents, conveying disappointment more than anger in the court's ruling.

“Justice Breyer only rarely reads dissents from the bench, and does so only when he feels strongly about a case,” said Hogan Lovells partner Neal Katyal, a former law clerk to Breyer. “While you will hear his strong views about the merits of a case, Justice Breyer even in spoken dissent is deeply respectful of his colleagues.”

In fact, Breyer ended his Jennings dissent this way: “With respect, I dissent.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

An ‘Indiana Jones Moment’: Mayer Brown’s John Nadolenco and Kelly Kramer on the 10-Year Legal Saga of the Bahia Emerald

Travis Lenkner Returns to Burford Capital With an Eye on Future Growth Opportunities

Legal Speak's 'Sidebar With Saul' Part V: Strange Days of Trump Trial Culminate in Historic Verdict

1 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Data Disposition—Conquering the Seemingly Unscalable Mountain

- 2Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

- 3Litigators of the Week: A Directed Verdict Win for Cisco in a West Texas Patent Case

- 4Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 5Womble Bond Becomes First Firm in UK to Roll Out AI Tool Firmwide

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250