Manafort Prosecutors Used the Few Tools Available to Confront Tough Judges

The Manafort judge's interventionist style prompted discussions in legal circles and on cable talk shows about whether he had gone too far, with some observers arguing the judge's hands-on approach and regular rebukes against prosecutors would have been fodder for a mistrial if the defense had been on the receiving end.

August 14, 2018 at 07:21 PM

6 minute read

The original version of this story was published on National Law Journal

Paul Manafort, former Trump campaign chairman, arrives at federal court in Washington, D.C., for his arraignment and bail hearing, on June 15, 2018. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Paul Manafort, former Trump campaign chairman, arrives at federal court in Washington, D.C., for his arraignment and bail hearing, on June 15, 2018. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

From the outset of Paul Manafort's bank and tax fraud trial, U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis III established himself as a force inside his federal courtroom in Alexandria, Virginia.

Far from sitting back and simply ruling on objections, Ellis often injected himself into the proceedings. Occasionally, he asked witnesses questions. He prodded prosecutors to pick up their pace, revealing from his own corner of the Albert V. Bryan Courthouse why the federal district court here is known as the “rocket docket.”

At one point, Ellis scolded prosecutors for allowing a witness to sit in on proceedings before taking the stand, only to later apologize after being told that prosecutors had received permission from the judge.

The interventionist style prompted discussions in legal circles and on cable talk shows about whether Ellis had gone too far, with some observers arguing the judge's hands-on approach and regular rebukes would have been fodder for a mistrial if the defense had been on the receiving end. If Manafort is acquitted—closing arguments are set for Wednesday—the government can't just appeal on the grounds of the judge's conduct.

“If the acquittal comes through, there's nothing you can do because of double jeopardy. It really is over,” said Shira Scheindlin, a former judge in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, now of counsel at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan. Scheindlin added: “The acquittal problem is almost insurmountable. The government has little recourse.”

Former prosecutors said the judge's treatment of the special counsel team could be cited by Manafort's defense in an appeal of any conviction. In such an appeal, they said, the defense might argue the judge's toughness had a “boomerang effect,” instilling sympathy among the jurors for the prosecution.

If the jury deadlocks and Ellis declares a mistrial, the special counsel's team does have some options. They could request a different judge, in a roll of the dice that whomever was assigned would take a less meddlesome approach.

“The best shot is, if there's a mistrial, between that and the next trial, you'd go after the judge,” Scheindlin said. “I have seen that. Short of that, I just don't see what you could do.”

In interviews, Scheindlin and former federal prosecutors said the special counsel team—under the supervision of Robert Mueller III, leading the investigation of Russia's interference in the 2016 election—has done essentially all that it can to deal with a difficult judge.

Prosecutors adapted to some of Ellis' more prickly ways—including his laser focus on keeping the trial moving and steering clear of what he views as unnecessary fluff.

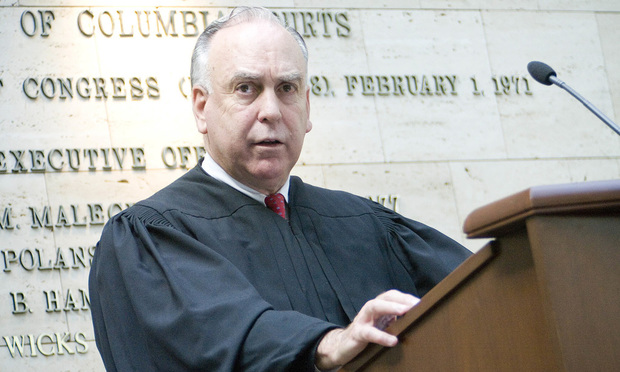

U.S. District T.S. Ellis III. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi/ National Law Journal

U.S. District T.S. Ellis III. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi/ National Law JournalOn Monday, when lead prosecutor Greg Andres showed an email to an executive at Federal Savings Bank, he told the witness to review the email but not read it aloud. When Ellis said the witness could read the email, since it was admitted into evidence, Andres said that wouldn't be necessary.

“Just wanted to move more expeditiously, your honor,” Andres said. (In a spillover room, some observers could not contain their laughter.)

In their dialogue with Ellis, the special counsel prosecutors have picked their battles but defended themselves when they felt it was necessary, said Randall Eliason, a former federal prosecutor in the District of Columbia.

“When you're the prosecution, you have very little recourse and about all you can do is basically what the prosecutors have done here: try stick up for yourself, try not to let the judge push you around, call out the judge when you think he's being unfair and request curative instructions when necessary,” said Eliason, who now teaches at George Washington University Law School. “Other than that, all you can do is keep your head down, try your case and trust that the jury decides based on the evidence rather than interactions with the judge.”

In one notable incident, Ellis berated prosecutors for allowing a witness—IRS Special Agent Michael Welch—to sit in on the trial before taking the stand. When assistant U.S. attorney Uzo Asonye challenged Ellis, telling him the witness had been approved to be in court before testifying, the judge shot back: “Don't do that again. When I exclude witnesses, I mean everybody.”

The heated exchange played out in front of jurors. The next day, prosecutors asked in a court filing for Ellis to give a “curative instruction” to the jury and make clear that he had, in fact, allowed the IRS agent and other expert witnesses to attend the proceedings.

“It appears I may well have been wrong,” Ellis later told the jury. “But like any human, and this robe doesn't make me anything other than human, I sometimes make mistakes.”

It would not be the prosecution's last request for a moment of judicial contrition.

After prosecutors questioned a Citizens Bank official about representations Manafort made in pursuit of a loan he did not ultimately receive, Ellis remarked in front of the jury: “You might want to spend time on a loan that was granted.” Prosecutors later filed a second request for curative instructions, arguing Manafort could be convicted of bank fraud conspiracy based on his representations to Citizens Bank regardless of whether he received the loan in question.

Asonye said the judge should give the jury a curative instruction to “avoid any potential prejudice to the government.” He argued that the judge's suggestion the “government was unnecessarily spending time on a loan that Manafort did not receive undermines the well-established law on conspiracy, undercuts the charge in count 28 [of the indictment], and is likely to confuse and mislead the jury.”

Ellis, before he gives the jury its instructions, will almost assuredly—as judges regularly do—tell the panel that nothing he's said over the course of the trial should be considered as evidence or as part of the credibility assessment of the witnesses.

Read more:

Closings Set for Wednesday After Manafort Declines to Testify at Fraud Trial

Quarrels Continue as Judge Pushes Prosecutors in Manafort Trial

OK, Got It, No More Photos Showing Manafort's Big-Spender Ways

Manafort Trial Judge Has Had It With Attorneys' Eye Rolling, Facial Gestures

Ellis Kim contributed reporting from Alexandria, Virginia.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

‘Listen, Listen, Listen’: Some Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

An ‘Indiana Jones Moment’: Mayer Brown’s John Nadolenco and Kelly Kramer on the 10-Year Legal Saga of the Bahia Emerald

Litigators of the Week: A Win for Homeless Veterans On the VA's West LA Campus

Trending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250