Litigators of the Week: Gibson Dunn's Estrada and Weigel Strike Gold in Venezuela Fight

Miguel Estrada and Robert Weigel's client wasn't the first company to have its assets seized by the government of Venezuela—but the Gibson Dunn duo was the first to come up with a viable way for them to collect what they're owed.

August 17, 2018 at 01:18 PM

8 minute read

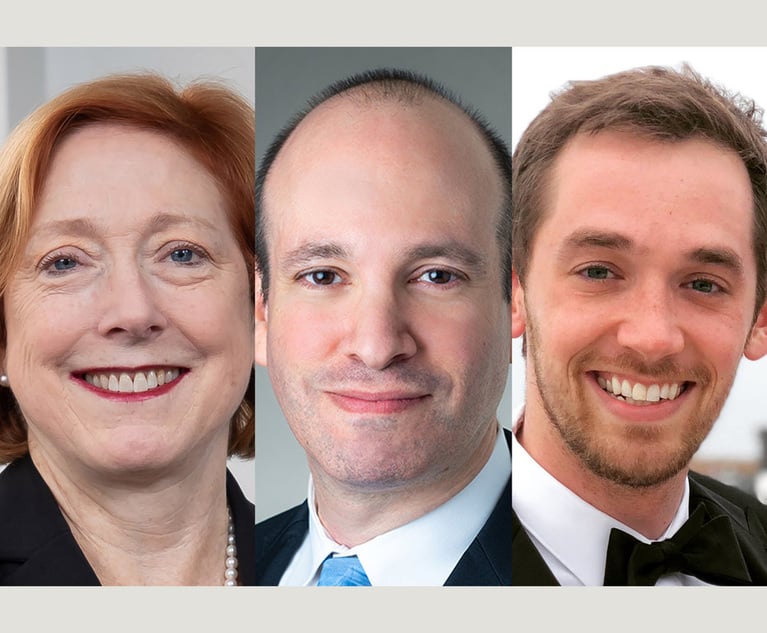

Miguel Estrada, left, and Robert Weigel, right, with Gibson Dunn & Crutcher.

Miguel Estrada, left, and Robert Weigel, right, with Gibson Dunn & Crutcher.

We're continuing our new Q&A format for Litigator of the Week, and had some great contenders for the crown. Our runner up was Antonio Yanez, Jr. of Willkie Farr & Gallagher. He led a team in favorably resolving a $75 million dispute with Netflix on behalf of client Relativity Media. Even more impressive, he was hired on July 5 for a case that went to trial on August 1.

But for our winner, we were swayed by a dispute with $1.4 billion on the line. Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher's Miguel Estrada and Robert Weigel represented a Canadian gold mining company that had its assets seized by the government of Venezuela. Their client wasn't the first company this happened to—but Estrada and Weigel were the first to come up with a viable way for them to collect what they're owed.

Lit Daily: Tell us a bit about your client and the circumstances leading up to the dispute.

Robert Weigel: Crystallex is a Canadian mining company that had been awarded the rights to develop Las Cristinas in Venezuela, a site many believe to be one of the largest undeveloped gold reserve in the world. After Crystallex spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing the site, the Venezuelan government expropriated Crystallex's interests. Crystallex brought an arbitration claim against Venezuela under the investment treaty between Canada and Venezuela.

A team of lawyers at Freshfields did a terrific job and won the arbitration. I was hired, along with a Gibson Dunn team including Rahim Moloo and Jason Myatt, because of our team's expertise in arbitration-related litigation and enforcement matters.

We started to look at enforcement issues early on and even brought a fraudulent transfer claim before the award was issued. After the award was issued and confirmed in the District of Columbia by a team of lawyers from Freshfields; Hughes Hubbard and Gibson Dunn, Miguel was brought in to handle the appeal.

Lit Daily: When Venezuela refused to pay the arbitration award, to what extent was there a template for how to proceed? Did you have to chart a unique path?

Robert Weigel: There is no template as every enforcement action is different. The key is to find the defendant's assets and then to design a strategy to go after them. Substantial investigative efforts are often required to identify assets. The means to seize or otherwise monetize those assets depends on the nature of the asset and its location. For example, the process for going after a bank account in New York or corporate shares in Delaware is different, so one has to build the process as one goes along.

Here everyone knew that Venezuela's biggest asset in the United States was Citgo Petroleum and that it was the target that we had to figure out how to get. But, we also located a bank account in New York that had tens of millions of dollars in it in Venezuela's name. The account had been the subject of litigation for more than a decade, and the plaintiff in that action had obtained a preliminary injunction preventing Venezuela from dissipating the funds. But a preliminary injunction doesn't create a lien and after we had the U.S. Marshals serve a writ of execution, which does create a lien, all the parties involved agreed on a division of those funds.

Lit Daily: Chief Judge Leonard Stark in the District of Delaware said the case presented “numerous complex questions, some of which have been addressed by no previous court, and others on which different courts have reached competing conclusions.” What were some of the key questions before the court?

Miguel Estrada: Venezuela fought very aggressively practically every legal and factual underpinning of our argument. At the threshold, they strongly disputed subject matter jurisdiction, contending essentially that we could not obtain an adjudication of the alter ego question in the context on an enforcement proceeding under Rule 69, but only by commencing a new and separate lawsuit against [oil and gas company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.], undergoing the cumbersome Hague Convention procedures for serving it, and separately defeating its purported sovereign immunity as a government agency of Venezuela.

They argued that the relevant Supreme Court precedent on alter ego provided for heightened burdens of proof. On the facts, they attempted to explain every damning fact in isolation and to put it in the best possible light. They left no stone unturned.

Lit Daily: I gather the court heard oral argument on two separate occasions. What was covered and how did it go?

Miguel Estrada: Because Venezuela attempted to erect so many procedural roadblocks to a decision, the oral arguments covered both procedural issues and the substance of the alter ego question. The original oral argument took place in court in Delaware and lasted several hours. I covered our response to Venezuela's jurisdictional challenges, and their many arguments based on the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, including some basic disagreements on the scope of the controlling Supreme Court decision, Bancec. Bob covered the extensive factual case we had developed for our argument on the merits.

I think it is fair to say that Venezuela's jurisdictional and immunity arguments, while meritless, were intricate and supported by reams of largely inapposite case law. This made for a lot of parsing. Judge Stark was meticulous during the argument in questioning both counsel extensively about doctrinal detail and case law, and it was clear he had taken a lot of time to ponder the issues. He then had a second oral argument by telephone, based on specific questions he had posed to both counsel about their respective positions and particular cases. Essentially, it felt like he was giving both parties a chance to clarify their positions and to try to convince him.

Lit Daily: What were some of the greatest challenges in litigating this case?

Robert Weigel: For me, the major challenge we faced was developing a factual record that was adequate to persuade the court that [Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.] was Venezuela's alter ego without the use of any discovery from Venezuela or PDVSA. Venezuela knew everything about its relationship with PDVSA. We did not.

Our team combed the public record in order to make our case, and we looked at everything from financial disclosures, press releases, and government proclamations to posts on Twitter and YouTube videos showing the President of Venezuela firing PDVSA employees on national television using a soccer whistle. The hard work paid off as we were able to locate overwhelming evidence that the government controlled every aspect of PDVSA's existence. As a result, the court found that PDVSA and Venezuela are one and the same.

Lit Daily: Was there a moment or two that stands out to either of you personally during the course of the litigation?

Robert Weigel: It was a delight to argue beside Miguel, who is just so smart and quick on his feet. My favorite point was when Miguel took out his cellphone mid-argument and pulled up an old Supreme Court case he knew from memory and quoted it to Judge Stark to refute an unanticipated argument that the other side had made.

Lit Daily: Did you make any unconventional strategic choices?

Robert Weigel: One of the very first things we did for Crystallex after we were retained was to bring a Delaware Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Action challenging more than $2.2 billion in dividend payments to PDVSA that were funded by CITGO Holding, Inc.—the holding company between PDV Holding and CITGO Petroleum—taking on billions of dollars of debt for no commercial purpose.

What made the move unconventional is that we filed the action before the arbitral award was issued, arguing that because the transfer occurred while the arbitration was pending it could be undone because it had been made to hinder recovery efforts of a future creditor.

The district court upheld the complaint, but the Third Circuit ultimately found, in a split decision, that while Venezuela and PDVSA had worked to hinder and delay creditors, the allegations didn't align with the elements of the statute and remanded the case back to the district court.

Proceedings to amend the complaint to address the Third Circuit's concerns were ultimately stayed pending the decision in this case—but the fraudulent transfer action helped signal to Venezuela that Crystallex was serious about collecting on its award and wouldn't go away quietly. And to this day Crystallex continues to work to satisfy its judgment.

Lit Daily: What happens next?

Miguel Estrada: PDVSA has filed a notice of appeal. In the meantime, Crystallex will advise the court on the execution process and continue to push forward with efforts to attach and ultimately sell the shares.

Lit Daily: What makes this case significant?

Miguel Estrada: Crystallex is now the first of Venezuela's many judgment creditors to successfully reach a significant asset to satisfy the country's obligations.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Litigators of the Week: Shortly After Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan’s Retirement, Quinn Emanuel Scores Appellate Win for Vimeo

Litigators of the Week: A Knockout Blow to Latest FCC Net Neutrality Rules After ‘Loper Bright’

Litigators of the (Past) Week: Defending Against a $290M Claim and Scoring a $116M Win in Drug Patent Fight

Litigation Leaders: Jason Leckerman of Ballard Spahr on Growing the Department by a Third Via Merger with Lane Powell

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250